Old Time Farm Crime: The Cutthroat World of Victorian Orchid Hunters

Orchid crime is serious business.

Old Time Farm Crime: The Cutthroat World of Victorian Orchid Hunters

Orchid crime is serious business.

“How long I shall stay up there I cannot tell, I came down here today and I can tell you, only dire necessity has driven me to it, I had nothing to eat, to come down and then to climb again 3,000 feet … is not like taking a walk on London Road on a Sunday afternoon,” Micholitz groused to Sanders in a letter sent from Padang in January 1891.

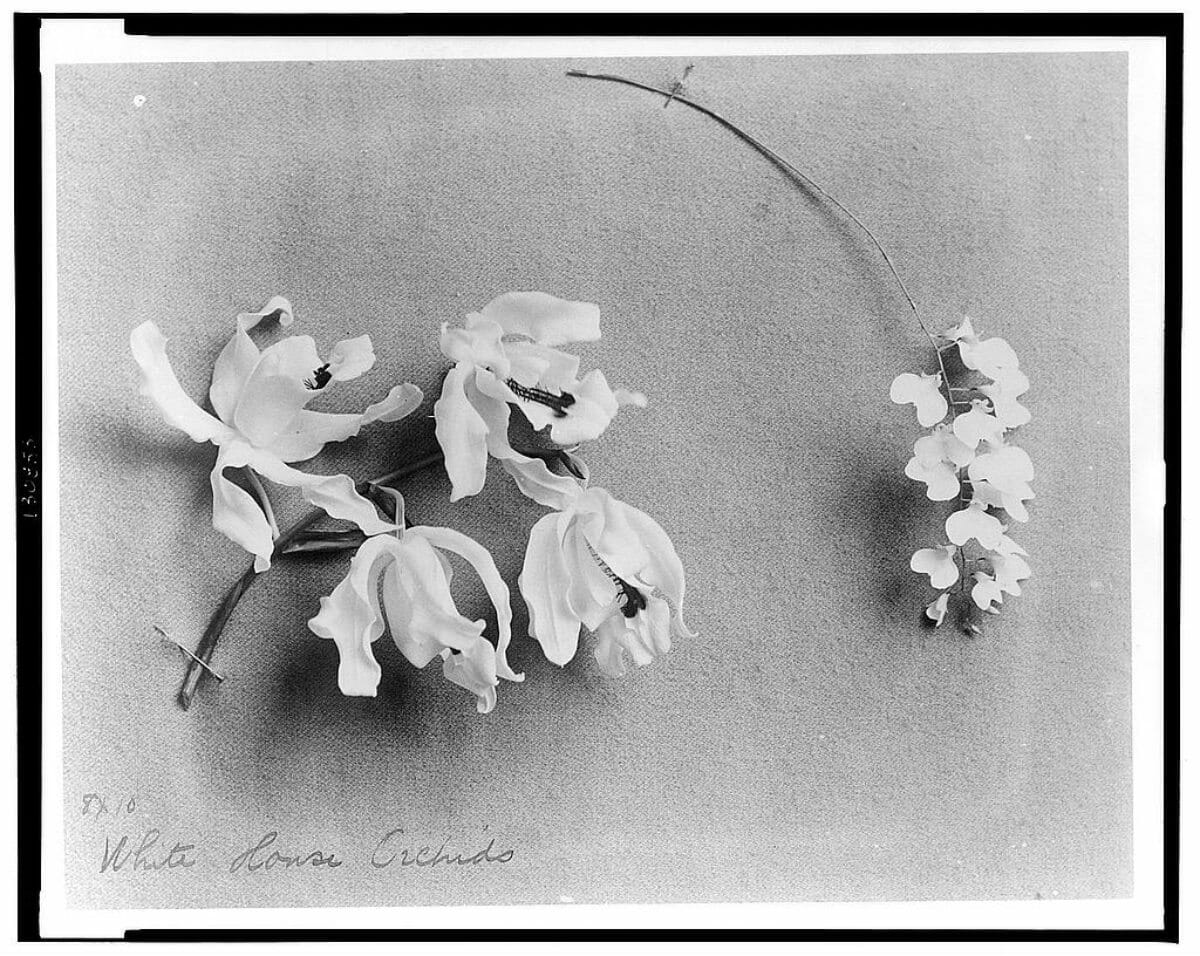

When In 1818 the naturalist William John Swainson sent back the first orchid specimen seen in London, orchid madness was born. Soon rich collectors were sending hunters far and wide into the wild to try and collect new and rare examples, reaching its heights in the Victorian era (mid-1830s to early 1900s). These hunters were a wild bunch who took their work to extremes with many dying in the pursuit.

Besides the treacherous terrain, tropical diseases, angry indigenous populations and vicious animals, they had to worry about their fellow orchid hunters.

Another of Sander’s hunters, William Arnold, once pulled a gun on a rival and the two nearly came to a shootout shipboard heading to Venezuela. Arnold was later instructed by his employer to follow the man – who worked for Sander’s nemesis, Dr. John Lowe – collect the same type of flowers he did and urinate on the other man’s specimens to destroy them.

Even the less irascible hunters followed their rivals and tried in subtle ways to derail their efforts. In July 1876, Friederich Carl Lehmann followed Edward Klaboch around Ecuador in order to collect plants from the same locations and then attempted to poach Klaboch’s local assistant.

“Sander, one of the largest employer of these bad boys of horticulture, was an avid orchid aficionado who at the height of his career employed 23 orchid hunters scattered across the world.”

“Lehmann is being a nuisance, he follows me everywhere,” complained Klaboch, yet another of Sander’s men, in a letter to his boss. “[Lehmann] went to see [a local man who collects orchids for me] and told him that he would pay one dollar more than we per 100 plants, and he wanted him to collect for him.”

Lehmann got his comeuppance. Klaboch’s man refused to help him and ratted out Lehmann to Klaboch. Klaboch promptly confronted Lehmann, who denied the exchange, saying the local man was a liar with the result that no one in the village would give Lehmann the time of day. Klaboch also gloated that he had collected more orchids than Lehmann. Schadenfreude seems to have been a common feeling among these mostly solitary men.

The life of an orchid hunter was far from romantic. Besides the various geographic and meteorological pitfalls, there was the basic problem of getting the plants from where they were found to the base camp. From there they would have to be dried and packed and then carted overland to the coast by hand, horse, elephant or Llama (depending, obviously, on where the orchids were discovered). A long sea journey to England came next. Finally, with a little luck, the plants would have survived the hardships and produce flowers to awe the rich willing to shell out cash, mainly at auctions held to buy and sell the exotic wonders.

“Ten thousand plants may be collected on some remote Andean peak or Papuan jungle with infinite care, and consigned to Europe, the freight alone amounting to thousands of dollars, yet on arrival there may not be a single orchid left alive,” wrote the reporter William George Fitz-Gerald.

Sander, one of the largest employer of these bad boys of horticulture, was an avid orchid aficionado who at the height of his career employed 23 orchid hunters scattered across the world and had a sprawling orchid farm in St. Albans, near London.

There, in 60 greenhouses specially adapted for the specific conditions needed to grow each orchid variety. The company handled between one and two million plants there in the 1880s and 90s. Sander also had space for testing and cultivating hybrids. As the business continued to grow, Sander built a orchid nursery in New Jersey and another in Belgium, which had 50 glasshouses for orchids.

Orchids were big business, with truly exotic plants fetching thousands of dollars each and trading from collector to collector pushing prices ever higher.

Sander told of one such exchange. He and a Liverpool lawyer were walking through one of the greenhouses when a particular orchid plant that hadn’t yet flowered caught the attorney’s eye. He purchased the plant from Sander for $12. Five years later he sold it back to Sander for $1,000, or the equivalent of $24,390 in todays dollars.

Sander was born in Hanover, Germany in 1847 and at age 20 began working for a London seed company. He soon fell in with the intrepid Czech plant collector and adventurer Benedikt Roezl and went into business. Roezl was a one-handed dynamo who traveled, mainly on foot, across the Americas collecting orchids and other plants. On one trip alone, traveling from Panama to Venezuela, he sent back eight tons of orchids to London.

Roezl turned to orchid hunting after a farm machine he invented to extract plant fiber took his hand during a demonstration in Mexico where he was living. He began hunting orchids after the accident, as he found farming difficult due to his impairment. Fitted with an iron hook, his prosthesis was apparently popular with local Indians, who would bring him plants. His obsession ran in the family. Klaboch, the hunter who was followed hither and thither by a rival in Ecuador, was Roezl’s nephew.

These orchid hunters desire for discovering and collecting, and the insatiable demand for the flowers in Europe and America, was devastating to the native orchid populations as well as the trees on which the epiphytic flowers grew.

These orchid hunters desire for discovering and collecting, and the insatiable demand for the flowers in Europe and America, was devastating to the native orchid populations as well as the trees on which the epiphytic flowers grew. There are still areas in Central and South America in which the plants never recovered. Today, many countries have laws in place to stop the wholesale stripping of orchids and other plants from their native habitats.

The hunters themselves became a dying breed, literally. Sander, during an interview in 1906, tossed off more than half-a-dozen names of his hunters who had been killed tracking down his flowering treasures. Arnold was killed while on a collecting expedition along the Orinoco River and Klaboch died in Mexico. Micholitz, while surviving the life of an orchid hunter, died in near poverty in Germany.

“All these [men] have met more or less tragic deaths through wild beasts, savages, fever, drowning, fall or other accidents,” Sander told Fitz-Gerald.

Leon Humboldt, a French orchid hunter, remarked that after a dinner with six other hunters in Madagascar, four were dead within four years. Two years later, Humboldt was the only survivor.

Orchid mania eventually went the way of these hunters, mainly thanks to the discovery of how to grow the plants from seed, a problem that was on its way to being perfected by the 1920s. These exotic blooms have now become a standard flower shop product and the intrepid hunters who once risked their lives to find them and the inflated prices the wealthy Victorians were willing to pay for the blooms have been resigned to history.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Andrew Amelinckx, Modern Farmer

August 1, 2014

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.