Ramps may be seemingly ubiquitous on the East Coast this time of year, but where do they come from? Our correspondent takes a trip to West Virginia to meet that rare breed, a ramp farmer.

A surveillance camera lurked under the Japanese larches and, further up the hollow, a horse grazed in front of the old wooden house where Glen Facemire, Jr. grew up. Born in Richwood, West Virginia, his family once raised Jersey cows on a steep, north-facing slope.

Here, more than a decade ago, Facemire planted his first 17-acre patch of ramps.

When I called him late one afternoon in mid-April, Facemire answered the phone, “Ramp farm!” He sounded like the excited host of a call-in radio show until I asked about visiting. “What’s in it for me?” He warned me that his ramp patch was within shotgun range of the back deck.

While this isn’t a rational response to my query, ramps are an undeniably precious commodity. (There’s even a black market for ramps in Quebec, where harvesting has been outlawed since 1995.) For a short couple of weeks each spring, the white, scallion-shaped bulbs send up two to four silken leaves up and down the East Coast, from Canada to Mississippi. They exude a distinctive, pungent aroma, the potency of which is said to reflect the soil where they are grown. Some call the ramp “Lazarus root.” (Bible refresher: Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead; the Gospel according to John 11:39 says, “He stinketh: for he hath been dead four days.”) The ramp was featured in early copies of the Lee Brothers Boiled Peanuts Catalogue and Martha Stewart Living and its popularity has only continued to grow.

But actually few actually farm the plants. Facemire’s operation, located in the self-described ramp capital of the world, underscores the paradox of the ramp: Seemingly ubiquitous but only available for a short time, it’s hard to say whether ramps are over-exposed or an endangered species. Facemire began his crop as a response to a fear of losing a signature plant of his region, but many says his concern is baseless. His operation hinted at the mystery of spring’s short-lived mania.

[mf_h4 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Trend or Tradition?[/mf_h4]

Some critics belittle ramp mania as an insidious food fad. But the undeniable truth was that, until recently, nearly every ramp came from the wild. That was the problem: Ramps were a potentially threatened species that rarely grew under cultivation owing to what some experts claim is a complex cycle of multiple dormancy. No one knew if its population was in precipitous decline or, in a classic case of shifting baselines, no one had ever really known what was out there to begin with.

[mf_list_sidebar layout=”basic” bordertop=”yes” title=”Ramps: Everywhere or Extinct?” separator=”no”]

[mf_list_sidebar_item]But are ramps really threatened? Depends on who you ask. When the bulb is dug up and harvested, ramps were slow to regenerate. It appeared to take decades for a patch to recover. Jim Chamberlain, a U.S. Department of Agriculture scientist in Richmond, Virginia, compared it to cutting down trees. “Fundamentally, it’s like logging old-growth,” he told me a couple years ago. “I’m not saying we shouldn’t do it, but we need to figure out how to do it sustainably. I’m all for using and conserving plants like ramps, or ginseng and things like that. But we need to figure out how to manage it, just like we do timber.” [/mf_list_sidebar_item]

[mf_list_sidebar_item]At the same time, ramps were little more than an ephemeral forest crop, an overlooked species whose vast biological abundance appeared to dwarf the dining demand. Bruce Richardson, a burly man who runs the Four Seasons Outfitters in Richwood and was buying 50-pound lots of ramps for $2.50 a pound (and selling a $439 gun) when we met, told me, “There’s always going to be ramps. I don’t ever see ramps ever deplenishing myself.” [/mf_list_sidebar_item]

[/mf_list_sidebar]

Facemire represented a vanguard of farming: He was one of the few, if not the first, who intentionally seeded his timberland with ramp seeds. He believed commercial exploitation had exacted an irreversible toll. Either that, or Facemire was clinging to the ramp as a cultural icon, a practical necessity, a surefire method for staving off scurvy in the spring, a decent way to make a living. As Richardson, notes, “Not many people get $250 dollars in a days work.”

Ramps were inextricably bound up in Appalachian identity: Jim Comstock, the publisher of the West Virginia Hillbilly, a now-defunct newspaper published in Richwood, once added ramp juice to his printer’s ink; the postmaster made him promise never to do it again. If the plants impending doom was unjustified or overblown, in recent years, nonetheless, ramp feeds and ramp festivals and ramp conventions migrated northward. As one paper published in the journal Material Culture put it, “The ‘placelessness’ of many of the new festivals necessarily raises questions of authentic experience, and clouds the symbolic meaning that ramps have historically imbued in Appalachia.”

Were the threats about shotgun blasts a way of preserving a regional identity? Or did Facemire have a genuine reason to be paranoid of poachers coming in from New York?

I decided to find out.

[mf_h4 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]On the Ramp Farm[/mf_h4]

I knew the ramp farm was somewhere in Richwood and the day after I called, I drove to the town. Richwood, population 2,039, is home to the longest, continuously running festival celebrating America’s native wild leek. (It started in 1921 and while one festival in Crosby, Tennessee, as I seem to remember reading, predates the one in Richwood, it wasn’t held this year. Perhaps there were others, at Legion Halls or churches, but Richwood’s claim seems to hold.) In Brooklyn or Baton Rouge, ramps might fetch up to $20 a pound; here, I was told, you could get a mess of ramps, bacon, beans, biscuits for less than that.

Everyone I asked knew the name Facemire, but no one could say where Glen Facemire, Jr. lived. One guy pumping gas told me Facemire owned the building two houses down. No one answered the door and a pile of broken bricks lay on the sidewalk.

I finally asked at the hardware store and they gave me an address and told me to go over the river. I couldn’t find the place but a neighbor pointed me straight up a hill: Facemire, he said, lived just outside the town line.

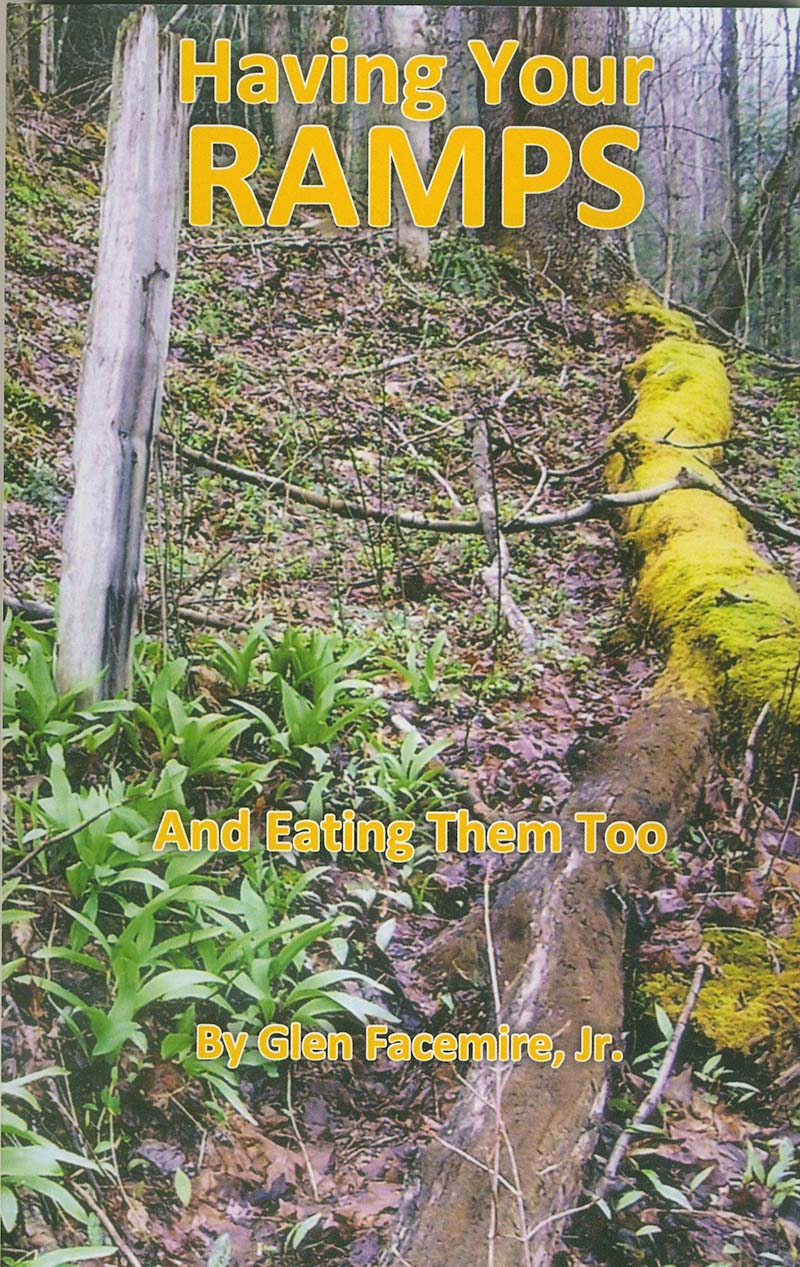

An unsteady man, in a khaki chamois shirt and corduroys, stepped out of his house and greeted me that afternoon. Facemire said he’d seen me coming down his driveway on the security camera. I convinced him I wasn’t going to poach any of his ramps. He showed me his collection of rusty, ramp hoes – their blades welded out of old car springs – and he urged me to purchase his book, “Having Your Ramps: And Eating Them Too” (McClain Printing Company, 2008). Down in the valley, a sawmill whistle blew down and a rooster crowed somewhere as we walked around his grassy lawn, which overlooked the shady patch of ramps. For nearly a decade, he said, he’d harvested little black seeds by the bucketful. These ramp seeds were about the size of No. 4 or No. 8 shotgun pellets – glossy, little marbles the color of deer droppings. Now, the seeds sprouted in neon green flushes under the water birches and beeches.

“If it weren’t for Johnny Appleseed, where would the apple trees be?” he said, “You got to replace what you take. It’s just not man’s nature to do it.”

He pointed to a mangled tree at the edge of the forest. “It’s fine if you want to tell people to go in and harvest small clumps of ramp. But you got to tell everyone that shows up. That ain’t going to happen. One guy goes in and harvests 20 percent that leaves 80 percent, another guy goes harvest 20 percent, now there’s 60. Let’s get real. The only way you’re going to be real about it is having your own little ramp patch.”

The patch still required work and as the afternoon wore on, Facemire’s vision for more ramp farms got clouded with religion and politics. “People don’t even want to work,” he said. “The Bible says if you don’t work, you don’t eat. The whole system is going to pot because people don’t want to work and invest and be responsible. They’re just dumbing around. They never did work. I could preach on.”

As I crept my rental car down the windy, single-lane road back towards the ramps capital of the world, I thought about the gospel according to Facemire: “It’s one thing to be ignorant. It’s another thing to stay that way. Just cause you know everything don’t think that you can’t learn something.” In other words, plant more ramps than you take and keep your ramp patch within shotgun range.