Two pig-tattooing artists - and the world - clash over porcine art.

After visiting the swine-friendly streets of a 19th-century New York City, when livestock were still a common sight in urban settings, Charles Dickens implored the readers of his 1842 travelogue, American Notes for General Circulation, to “take care of the pigs” because, as he wryly put it, the “gentlemen hogs” were “mingling with the best society, on an equal, if not superior footing, for every one makes way when he appears, and the haughtiest give him the wall, if he prefer it.” His sardonic admiration for the humble hog’s status was a pointed barb at “haughty urbanites” who conceded their space to swine. Pigs, of course, vanished from New York City streets as the urban and rural grew ever more separate. But 135 years later, in Denton, Texas, an artist returned hogs to the realm of the sophisticated, by exhibiting a live little piggy named Minnesota, flanked with resplendent tattooed wings no less, in a gallery for all to see.

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]***[/mf_h5]

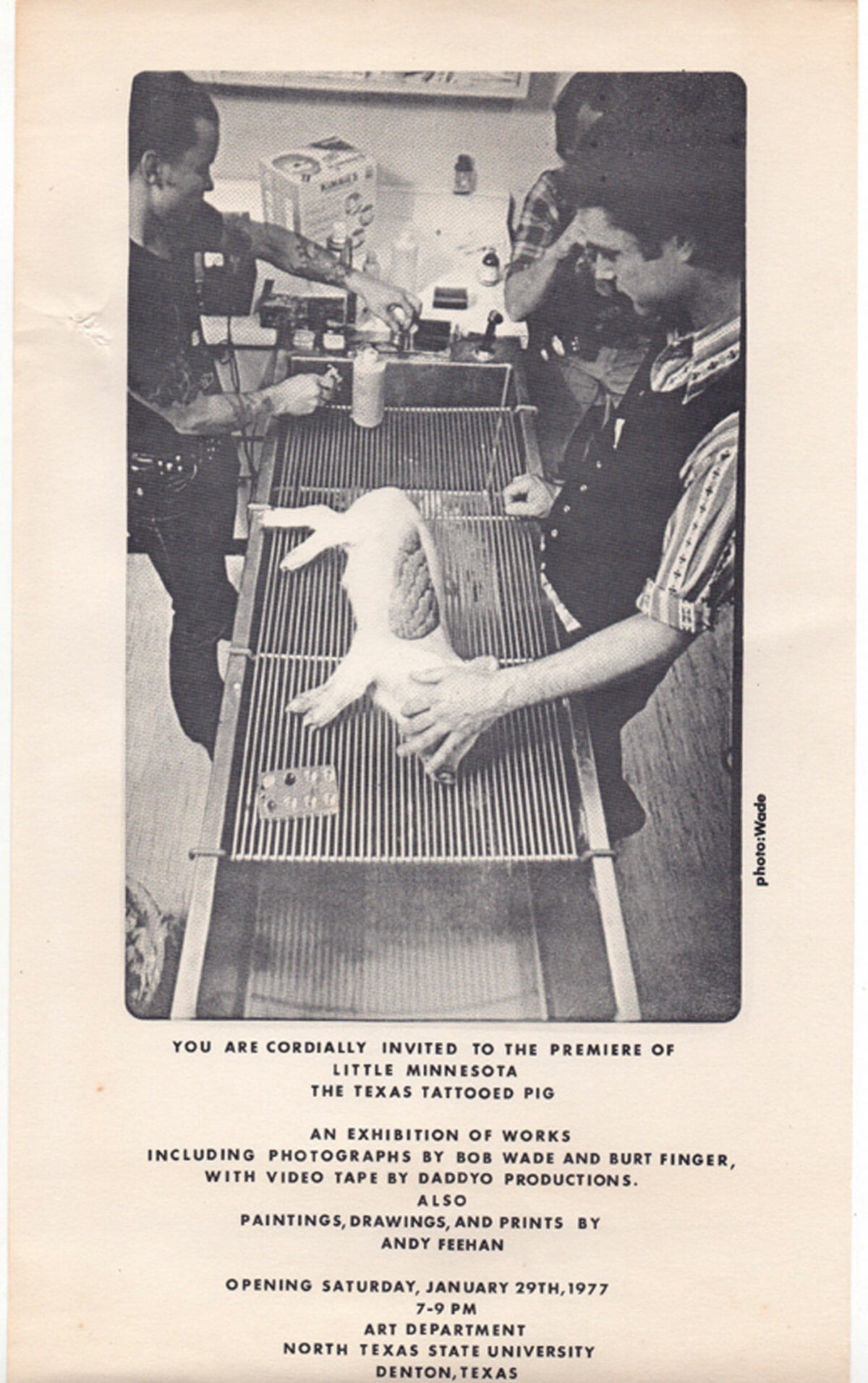

In 1977 Andy Feehan was completing his master of fine arts at the University of North Texas when he made an unconventional and, to some, disturbing choice. For his project, “The Tattooed Pig as an Aesthetic Dialectic,” he tattooed large wings on a small Chester White, a breed of domesticated pig ideal for husbandry owing to years of selective breeding.

“I wanted to extract them permanently from the pig factory,” He told writer Susie Kalil in Artlies magazine in 2000, “I wanted them to be art. I wanted them to have an unusual life of luxury, like a pet, like a precious weird animal in the circus of humanity.”

‘I wanted to extract them permanently from the pig factory. I wanted them to be art. I wanted them to have an unusual life of luxury, like a pet, like a precious weird animal in the circus of humanity.’

He told Kalil he hoped it would cause people to reconsider how they felt about eating meat and that the wings were a nod to the escape of the animal from the slaughterhouse.

As Feehan planned his project, his research led him to studies that detailed similarities between hog and human skins. His confidence bolstered, he set about trying to obtain a pig. In an email to us, Feehan explains that the very act of trying to purchase a pig for the project revealed contradictions in the way people approve of using animals.

Feehan says he tried to obtain pigs from the Hanford Site, a U.S. government testing facility that developed Hanford Minature Swine specifically for laboratory testing, and was refused. He also said he contacted a laboratory that was intoxicating the same breed of pig with alcohol and performing necropsies, and they also turned him down. In both cases, Feehan says the labs refused to supply him with pigs because what he had in mind was inhumane, an irony that was not lost on the artist: “What I wanted to do in the name of art wasn’t cruel at all compared to what I saw done in the name of science.”

Eventually, Feehan visted a hog farm near Denton and purchased a two-month old Chester White pig, who he named Minnesota.

For his project, Feehan employed a professional veterinarian and a tattooist.

“I was turned down by at least a dozen tattooists, veterinarians, and laboratories before I found a team that would accept what I was doing,” he says.

Minnesota the pig was administered an injection of sodium pentobarbital, which rendered him unconscious. He was shaved, coated in a liberal amount of green tincture soap, which is commonly used to prep human skin for tattooing, and the tattoo stencil was transferred onto his body. The tattooist, Randy Adams, started with the outline of the wings, then the feathers and finished with color shading. The next day Minnesota woke up, as Feehan proudly asserts, “the only winged pig in the world.”

Feehan’s project had no shortage of detractors who decried the work as an act of animal cruelty, something that Feehan denies.

“I believe the manner in which I had the pig tattooed was as humane and painless as possible . . . My intention was, in addition to making them art, was to save their lives,” he wrote.

That wasn’t the assessment of Kim J. Campbell, who wrote about Feehan’s MFA thesis exhibition in the February 4, 1977 edition of The North Texas Daily. A drizzle of swine urine trumped Feehan’s sincere intentions, according to the critic:

“Suffering through a tattooing is humiliating enough, but having the operation photographed and videotaped is outright overkill. The slippery plastic flooring compounded Little Minnesota’s embarrassment as he tried in vain to maintain his footing at Saturday night’s debut…Maybe it was Little Minnesota, the Texas Tattooed Pig, who finally made the most sincere statement of the night when he urinated in his plastic pigsty,” wrote Campbell.

Campbell’s comments revealed what the artists were “up against” Feehan writes.

“I did the project when the world was very different. It was difficult then . . . Both tattoos and weirdness in general (even in Texas) were fighting an uphill battle for existence, much less acceptance.”

After the exhibit, Minnesota became Feehan’s pet. Although the artist and his two dogs developed a strong bond with the pig, urban living arrangements behooved his subsequent gifting of the pig, on the condition he never be slaughtered. Later, a man from Santa Fe commissioned Feehan to tattoo another pig. The pig was named Artemis, and was to be given as a gift to a former congressman. Feehan agreed, provided the pig would live like a family pet.

But, as works of art, the pigs were high maintenance. Eventually, both pigs were slaughtered. Minnesota’s owner had him stuffed. Feehan was left feeling as though the whole purpose of tattooing the pigs was defeated.

During the 2000 interview, Kalil asked the artist if Minnesota would be received differently today. He surmised that today’s audience might not be so quick to label the work as cruel. “We’ve seen so much since then,” he said.

But outrage over the act of tattooing pigs has not waned, nor has the strange history of tattooed pigs ended with Feehan.

Artist Wim Delvoye followed in Feehan’s foosteps. He began tattooing pig skins starting in the 1990s and eventually moved on to live pigs. He decorated swine with everything from images of daggers to Disney princesses, and has showed live tattooed pigs at exhibitions. Eventually he took the experiment a step further, establishing an “art farm” in Beijing, where pigs were raised exclusively to be tattooed with his artwork. The pigs were killed and their flattened skins sold to customers who display them as works of art. The industrialization of his work became a commentary on art-industry demand.

A Facebook page devoted to the artist offers ample proof that plenty of people are outraged by the tattooed pigs. Commenters call the work ugly, sadistic and disgusting. Devoyle is called a bastard. “YOU ARE NOT AN ARTIST!,” writes one angry commenter. “You are not expressing anything. You are a little man craving attention by bullying those weaker than you. You are a psychopath animal abuser. This is not conceptual art. It is the torture and killing of innocent, unwilling creatures. May you rot slowly of an incurable disease you waste of space.”

The casual observer might think that two men who both tattoo pigs could find a common ground, even friendship. They would be wrong.

In an interview for Antennae magazine, Delvoye was asked if he might have the capacity to form a close bond like Feehan did with Minnesota and Artemis, that would prevent him from killing his pigs for customers.

[mf_1200px_image src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/oinked2.jpg” caption=”Wim Delvoye washes his tattooed pigs at a farm in rural Beijing on July 14, 2005. Shown are tattoos of mermaids and roses, cherubs, Lenin’s head and the pattern of French brand Louis Vuitton.” captionposition=”none” credits=”REUTERS/Reinhard Krause (CHINA)” parallax=”off”]

Delvoye did not mince words.

“Listen to these arty-farty names,” he said. “How pretentious! My pigs are called Elisabeth, Henry, John, Wim, and Vladimir.”

I presented Feehan with an occasion to respond.

‘His work is derivative of mine. He is a careerist who saw my work published in the early eighties, and he nicked the idea . . . Delvoye is a hack.’

“Opinions,” he writes, “are like arseholes. Everybody has one. He is cruel. His work is derivative of mine. He is a careerist who saw my work published in the early eighties, and he nicked the idea . . . I was not interested in making a commodity or making money. Delvoye is a hack.”

Feehan and Devolye’s work had one very important thing in common, of course: tattooed pigs. But both used them to different ends. Feehan used art to emancipate several pigs from death row, intending them to live in luxury as abattoir ambassadors lobbying for a change in use-value. Delvoye replaced the meat-worker’s tools with those of an artist’s, using art to shackle pigs into a chain of production similar to when they are commoditized into sundry objects. Delvoye’s art farm “rescued” pigs en masse from slaughterhouses to sedate, shave and tattoo them. It was a costly operation, consisting of tattoo artists, pig carers, a skinner and a tanner and even a professional fly swatter, but with reports of the skins being sold for over $100,000, Delvoye was likely not out of pocket. The swine, up to 30 at any given time, lived indulgently, literally growing in value like a piggy bank until death. They were then skinned and sent to their new, urban stys – art galleries – until Delvoye’s farm ceased production in 2008: The Chinese Year of the Pig.

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]***[/mf_h5]

Stijn Huijts was director of The Domain Museum, a contemporary art museum in the Netherlands, during a 1998 exhibition of Delvoye’s tattooed pig Marcel. He wrote a piece on the experience, entitled “UBN 2408356 or Marcel’s Song.”

In it, he claims that, if taken from an intellectual standpoint Delvoye’s work may be considered immoral and criminal, but these concepts are universally amorphous. The pigs, he wrote, are “living proof” of the fact that a contemporary work of art can be a vehicle for ideas that question the validity of ethics and law.

Moral philosopher Peter Singer, who authored the influential book “Animal Liberation”, does not believe Delvoye’s tattooed pigs provoke the status quo.

“It probably just reinforces the prejudice that animals exist for us to use – if not for meat, then for art,” he wrote in an email. “It may be better for the pigs he tattoos than the fate that would otherwise have awaited them. Taking these pigs out of meat production will just mean that other pigs are bred to suffer. ‘Art’ is no excuse for failing to show respect and concern for animals.”

Feehan and Delvoye’s work, however, accomplish something that many food or animal rights activists would also like to do. The process of transforming these swine into consumable art parodies the process of commoditizing flesh into meat, and undeniably encourages, at the very least, further discussion about our relationship with swine.

[mf_editorial_break layout=”twocol” title=”The Art of a Pig’s Body”]Andy Feehan and Wim Delvoye are not the only artists to use the body of a swine as their medium. More recently, in her work Pig 05049, Dutch artist Christien Meinderstsma spent three years following the posthumous journey of a (eponymous) pig in order to uncover where its various parts came to rest. In total, she found 185 products containing vestigial elements of its skin, bones, meat, internal organs, blood, and fat. Pig 05049 was used as an ingredient to produce biodiesel, bread, medicine, photo paper, heart valves, chewing gum, porcelain, brakes, cosmetics, cigarettes, wine, beer, soap, and even ammunition. The transformation of fragmented body parts into sundry objects renders the pig irrevocably alienated from its entirety. It is within this public space bereft of intact, live hogs, that culture fills the void with fictitious illustrations of swine. The representation of these complete pigs as anthropomorphized characters in film and cartoons further helps to dissociate crude reality from plastic-wrapped pork chops.[/mf_editorial_break]

Fareed Kaviani is a masters of literature graduate, currently writing for the London publication, Things & Ink. You can find more of his writing at the4thwall.net