The winding and weird relationship between pigs and humans.

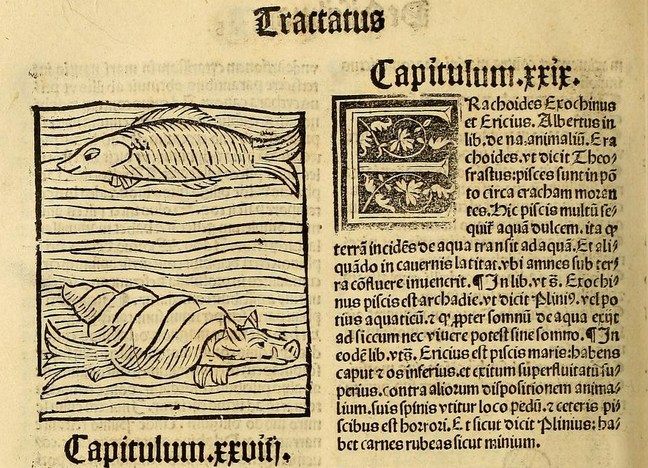

Thankfully, the pictured pigfish (fishpig?) was not meant to be eaten. The colored woodprint was included in Ortus Sanitatis, a late 15th century German guide to the medicinal uses of plants and animals. Alongside seemingly innocuous woodcuts of onions and sheep, the author included whimsical images of pigfish, mermaids, winged cows, and human children sprouting like Thumbelina from nondescript green plants.

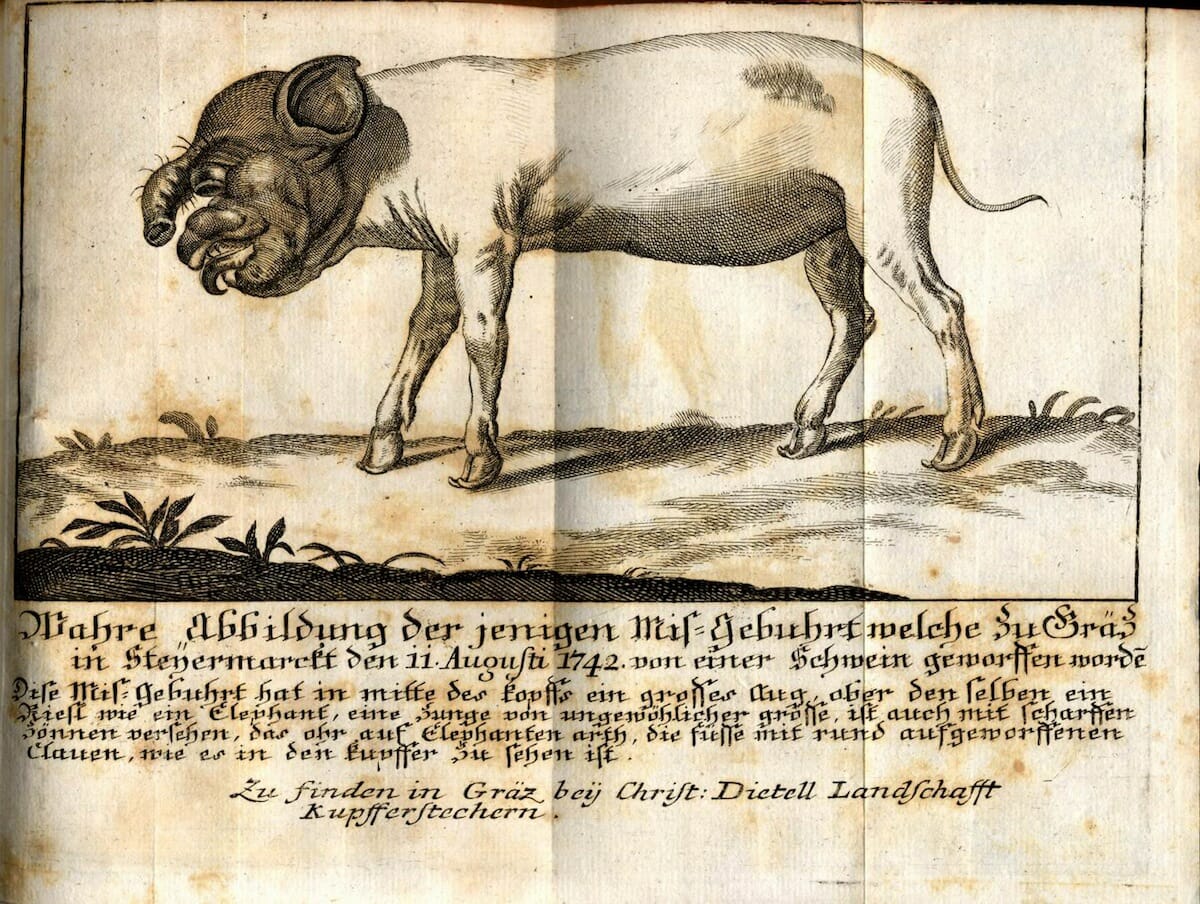

The pigfish wasn’t the only bizarre rendering of pigs in the olden days. The trend continued into the early modern era (roughly 1500 to 1800) as well. In England, pigs were the focus of witches’ spells that made them “leap and dance,” employed satirically to mock vain women and were used as guinea pigs (see what I did there?) to test vaccines.

Pigs were, especially, featured in single page broadsheets that documented “monstrous births.” These English broadsheets, especially plentiful in the 16th century, included cases of a pig so mutated that it lacked a snout and even a case of conjoined pigs. The English so demanded tales of these monstrous pigs that they even published the case of a Danish pig, imported to England, that had the ears of a lion, a wool covering like a sheep, and talon-like feet. The author seemed almost relieved to report that the pig ate “haye and grasse, as Breade and Apples, with such other thinges as sheep and Swyne do feede on.” At last, something recognizable about the creature!

Given the givens, it seems unlikely that anyone living in early modern England would want to eat pork, right? Yet, food scholars have noted time and time again that pork and pork products were a large part of medieval and early modern European diets. This was due to two reasons: As P.W. Hammond observed in his “Food and Feast in Medieval England,” pigs were easy to raise in both town and country. Joan Thirsk, in Food in Early Modern England, added that pigs had the added bonus of giving birth to large litters twice per year and yielding the most “bounteous supply of meat.” Thus, as early modern food historian Ken Albala has argued, pork was the most widely eaten meat across all class lines throughout Europe.

This might explain the obsessive nature with which early modern medical writers debated the health of pork products. Medicine, at the time, was largely based upon the theory of the four humours ”“ black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm. It was believed that all living things possessed these four humours in varying quantities and that health was dependent on the proper balance of each. Too much black bile, for example, and you would be melancholic. Too much yellow bile and you would be a grump! The humoural nature of food was key to one’s health.

Agreeing with Galen, the 2nd century Greek physician, most of these medical writers agreed that pork was, generally, a healthy meat. But this came with a lot of caveats. John Archer, a quack doctor who also served as physician to King Charles II, wrote that “swines flesh nourisheth very plentifully and yields firm nutriment.” Suckling pigs and boars were also deemed “nourishing” meats. The former, however, was not healthy for all people. Suckling pigs were considered to be a humid meat that, when consumed, allowed “fumous vapours” to ascend to the brain causing headaches and dizziness. Headcheese, as well, was considered to be incredibly unhealthy. As 16th century writer, William Bullein wrote, “pigges braines, and all slimie meates, bee euill for thee.”

Indeed. Slimy meats sound terrible.

In terms of the humours, pig’s flesh was considered a hot and moist meat, to be avoided by those of overly hot and moist humours. Medical minds thought superfluous blood and phlegm caused gout, historically the affliction of wealthy (and frequently obese) men. Pork, then, was to be avoided at all costs. In some cases, only specific types of pig’s flesh had to be avoided. A “cholerick” person, full of yellow bile, should not eat salted pork meats such as bacon, while a pork roast with currants or accompanied by “green sauce” ”“ a 17th century recipe suggests this was made with sorrel, eggs, vinegar, and butter ”“ was acceptable.

So when was pork actually good for you? Well, William Langham, a 16th century physician, agreed with Galen that pork was best eaten by healthy, active people. If not, pork ”“ specifically pig’s feet ”“ were especially good for the melancholic as it made the “veynes tender and moiste.”

Are you suffering from an overabundance of yellow or black bile? If so, I leave you with a 17th century recipe meant to balance out those humours:

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]”Take… fresh Pig-pork… let them simper ten or twelve hours by a soft fire, in a sufficient quantity of Springwater, with Mary-golds, Rosemary, Time, Savory, Sweet-marjoram, Mace, or Cinamon: when ’tis almost boil’d enough, add to it a crust of bread, then strain it: To make it more nourishing, put to it, as you eat it, the yolk of an Egg and Sugar.”[/mf_blockquote]

(Photos courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.)