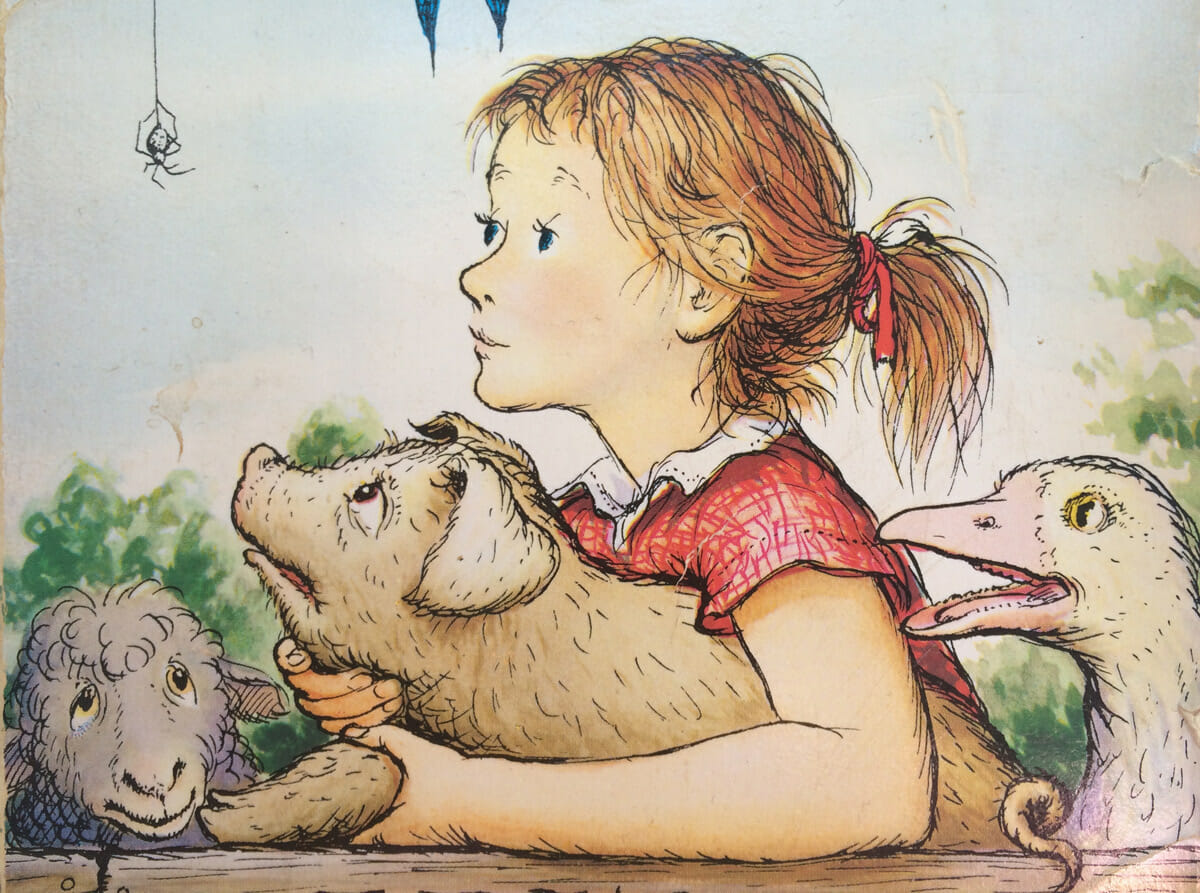

‘Some Pig’: E.B. White, Farming and ‘Charlotte’s Web’

The story behind the most famous pig of all.

‘Some Pig’: E.B. White, Farming and ‘Charlotte’s Web’

The story behind the most famous pig of all.

Brought to life by E.B. White, famed staffer at The New Yorker, Wilbur was a wonderful piece of fiction, but it wasn’t all make believe. White’s background as a farmer imbued Wilbur’s story with a ring of truth, helping it become a beloved classic.

“I don’t know of any book for adults or children that has the Sword of Damocles hanging over it as much,” says Michael Sims, author of “The Story of Charlotte’s Web: E. B. White’s Eccentric Life in Nature and the Birth of an American Classic”. “I mean, mortality’s scythe is right there in the first sentence, ‘Where is papa going with that axe?’ It’s like Hitchcock.”

White grew up in the suburbs of New York City, but learned a deep appreciation for the natural world when he contracted a bout of severe hay fever and, on the advice of a doctor, was taken to summer in Maine as a child. Eventually, he graduated from Cornell University and became an instrumental contributor to The New Yorker during its formative years. But, despite the fact he was a key player at a magazine that embodied New York’s urban sensibility, White did not really relish living in the city. In his early thirties he bought a farm in Brooklin, Maine, splitting his time between the city and the country before moving to the country permanently. He died at the farm in 1985. On the occasion of his death, William Shawn, editor of The New Yorker, said “He loved his farm, his farm animals, his neighbors, his family and words.”

White was not just a gentleman farmer. He raised chickens, turkeys, pigs and cows and carried out the daily duties of running a farm. Farming informed much of his writing and he published a book of essays about farm life called “One Man’s Meat” in which he writes “farming is about twenty per cent agriculture and eighty per cent mending something that has got busted. Farming is a sort of glorified repair job.” (White also writes of a pig that gives birth to a runt like Wilbur.)

‘He was very aware that the farmer was one who in a sense betrayed each animal at a certain point. That you cared for them, nurtured them and then cut their throat six months later.’

Sims says that he originally set out to write about the phenomena of children’s books starring animals but that once he began investigating White and “Charlotte’s Web,” he couldn’t stop: White’s relationship with nature was engrossing and unique. While some people would interact with an animal – say a bird in a park – and simply enjoy the moment and move on, White held tight to these memories, Sims says. They ran around and around in his head. He often wrote in the voice of animals, even penning a letter in the voice of his Scottish terrier, Daisy, to congratulate his wife on her pregnancy.

In the case of Wilbur, the pig that ran around and around in White’s head was the subject of a now-famous essay “Death of a Pig,” published in The Atlantic in 1948. In the essay, White describes a few days and nights during which he cared for a sick pig that eventually died. His concern for the animal – which was slated to become dinner if he survived – was great. “When we slid the body into the grave, we both were shaken to the core,” writes White. “The loss we felt was not the loss of ham but the loss of pig. He had evidently become precious to me, not that he represented a distant nourishment in a hungry time, but that he had suffered in a suffering world.”

“What I like about him, what I find interesting about him,” says Sims, “is that he could look straight at things and acknowledge the ambiguity and the irony and the moral iffiness of a situation. And just keep going. He did not become a vegetarian, he did not renounce farming. But he was very aware that the farmer was one who in a sense betrayed each animal at a certain point. That you cared for them, nurtured them and then cut their throat six months later.”

In a letter to his editor, Ursula Nordstrom of Harper & Row, White discusses the ambiguous role he played in the lives of his pigs and how that informed the plot of his novel: “Anyway, the theme of ‘Charlotte’s Web’ is that a pig shall be saved, and I have an idea that somewhere deep inside me there was a wish to that effect.”

Just how he would save the pig was not readily apparent, says Sims. Which is where the spider comes in.

White became fascinated with a large gray spider that lived in his barn that he would pass by when he went to carry slop out to the pig that replaced the one that had died. He watched as the spider fashioned an egg case, and then one day, he noticed she never reappeared. He realized she had probably died. He cut the egg case down with a razor blade, and (just as Wilbur would in the end of his book) commenced to carry it about with him, including on a trip into the city.

“I love the thought that here is E.B. White on the subway in New York City and in his pocket is the egg case that is going to inspire the most beloved children’s book of the 20th century,” says Sims.

‘Animals are the perfect way to deal with the battle of good and evil and the small creatures against the mean creatures. You can deal with things in fantasy that you can’t in realistic fiction.’

The egg eventually hatched in White’s city apartment, and he permitted the spider’s offspring to live alongside him. He proceeded to do a great deal of research into arachnids, eventually deciding that the spider’s weaving skills would be Wilbur’s salvation. Charlotte A. Cavatica would save Wilbur from the chopping block by spinning words like “TERRIFIC” and “SOME PIG” into a web suspended above his pen.

“My publicist insists she’s a publicist,” Sims says. “After all, all she is really doing is advertising Wilbur.”

Wilbur, Charlotte and their barnyard brethren are part of a long and ongoing tradition of animals in children’s literature.

“The animal just allows, especially in fantasy, the perfect way to deal with the battle of good and evil and the small creatures against the mean creatures,” says Barbara Kiefer, professor of children’s literature at Ohio State University. “You can deal with things in fantasy that you can’t in realistic fiction.”

Kiefer says children see themselves in the plight of creatures because “they’re at the mercy of other people or other animals. For the children who see themselves at the mercy of adults a lot of times, that kind of trope is an appealing theme.”

“Charlotte’s Web” satisfies a child’s desire for such a theme in spades, as Wilbur frets over being fattened, killed and eaten by his caretakers throughout the book.

“Charlottes Web” was published in 1952. The following spring, says Sims, White’s stepson Roger Angell, an accomplished sports writer and former fiction editor at The New Yorker, visited the farm with his daughter. White’s granddaughter had learned that a pig on the farm was slated for death, and having read her grandfather’s book, took it upon herself to try and save its life. She drew a picture inspired by “Charlotte’s Web,” and attached it to the pig’s pen for White to discover in the morning, just as Wilbur’s owners had discovered Charlotte’s message.

“E.B. White laughed and went up to tell his wife that this miraculous thing had happened in the night,” says Sims. “And then as far as I could find out, that fall he went ahead and killed the pig.”

After all, he was still a farmer.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Andy Wright, Modern Farmer

March 13, 2014

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.