Old Time Farm Crime: The Embalmed Beef Scandal of 1898

They say the beef smelled like an embalmed dead body. By the end of the scandal, it would irrevocably change how Americans dealt with their food.

Old Time Farm Crime: The Embalmed Beef Scandal of 1898

They say the beef smelled like an embalmed dead body. By the end of the scandal, it would irrevocably change how Americans dealt with their food.

But that alleged rank beef – along with a groundbreaking book – helped usher in modern food safety in the United States.

In 1898 the cry of “Remember the Maine,” a reference to the possible bombing of a U.S. battleship in Havana harbor, was whipping the country into a war frenzy. New York newspapers, especially those owned by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, helped rattle the sabers with lurid accounts of alleged atrocities committed by the Spanish in Cuba. The U.S. had been closely following the Cubans’ fight to free themselves from their colonial masters and when the Maine blew up under mysterious circumstances that February, killing 266 of her crew, it was only a matter of time before Spain and America would clash.

When war was declared in April 1898, the Army was ill-prepared for battle. At the time there were just over 28,000 available troops, but after a call for volunteers that numbers jumped by nearly 10 times, initially stretching supplies thin. Beyond this, there was little thought put into what changes would be required to fight in the tropics. Besides Cuba, the war would encompass both the Philippines and Puerto Rico. The men were issued heavy wool uniforms, had inadequate medical supplies, and rations that spoiled in the heat, forcing them to mainly subsist on canned beef that was stringy and tasteless at best and possibly sickened or killed some soldiers.

The commander of the Army, Gen. Nelson A. Miles, told a government commission investigating the handling of the war he believed the meat was “defective.”

The commander of the Army, Gen. Nelson A. Miles, told a government commission investigating the handling of the war he believed the meat was “defective.”

In Cuba, the troops ate the canned meat while in Puerto Rico the men were given a combination of canned beef and refrigerated beef, and it was this latter meat – 327 tons worth – that Miles was especially disturbed by, telling the commission the meat had an “odor like an embalmed dead body.”

“It was sent as food. If they wouldn’t have taken that, they would have had to go hungry,” he told the Dodge commission, which was named for Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge, who headed it up.

Miles believed the chemicals used to treat the meat were responsible for the “great sickness in the American army,” and said he had advised against the shipping of beef to Puerto Rico because there were adequate supplies available there.

He characterized the plan as an “experiment” for which “someone in Washington “was responsible. That person, he said, was The Commissary General of Subsistence, Brigadier General Charles P. Eagan.

“Reports were frequently sent in to [the Commissary General], but he seemed to insist that the beef be used,” said Miles.

Eagan vigorously defended his handling of the supplies during the war and of the quality of the beef in particular. Had he left it at that, things may have subsided, but the hot-tempered general instead went on a mellifluous tirade against Miles and called him out like only a Gilded Age gentleman could.

“He lies in his throat, he lies in his heart, he lies in every hair on his head and every pore in his body,” he began, just getting started. “I wish to force the lie back in his throat, covered with the contents of a camp latrine.”

Eagan heaped contempt on his superior officer, telling the commission that Miles should be barred from polite society.

Eagan’s lawyer called his client’s ranting “the natural outburst of a man suffering under an unjust accusation.” Eagan’s superiors called it “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.” He was court martialed and dismissed, but President William McKinley commuted the sentence and put Eagan on paid suspension for close to two years and then allowed him to retire.

The Dodge commission determined that there was nothing wrong with the beef and that the confirmed cases of food poisoning were due to some canned beef being mishandled.

The commission found that the refrigerated beef was not “subjected to or treated with any chemicals” and that shipping the beef from the U.S., rather than procuring fresh meat in Puerto Rica, “was wise and desirable.”

But the controversy wouldn’t die. Eventually a so-called military Beef Court (yes, there is such a thing as Beef Court) was convened with the task of trying to get to the bottom of the embalmed beef issue. In an investigation that lasted nearly as long as the war itself, the court came up with similar findings as the Dodge commission, concluding that Miles had made unjustified allegations concerning the refrigerated beef. The court also chastised Eagan for procuring thousands of pounds of canned beef that was “practically untried and unknown.”

Perhaps the embalmed beef story would have ended there but for two events: the publishing of “The Jungle,” – a muckraking novel written by socialist journalist named Upton Sinclair – and the assassination of McKinley, which elevated Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency.

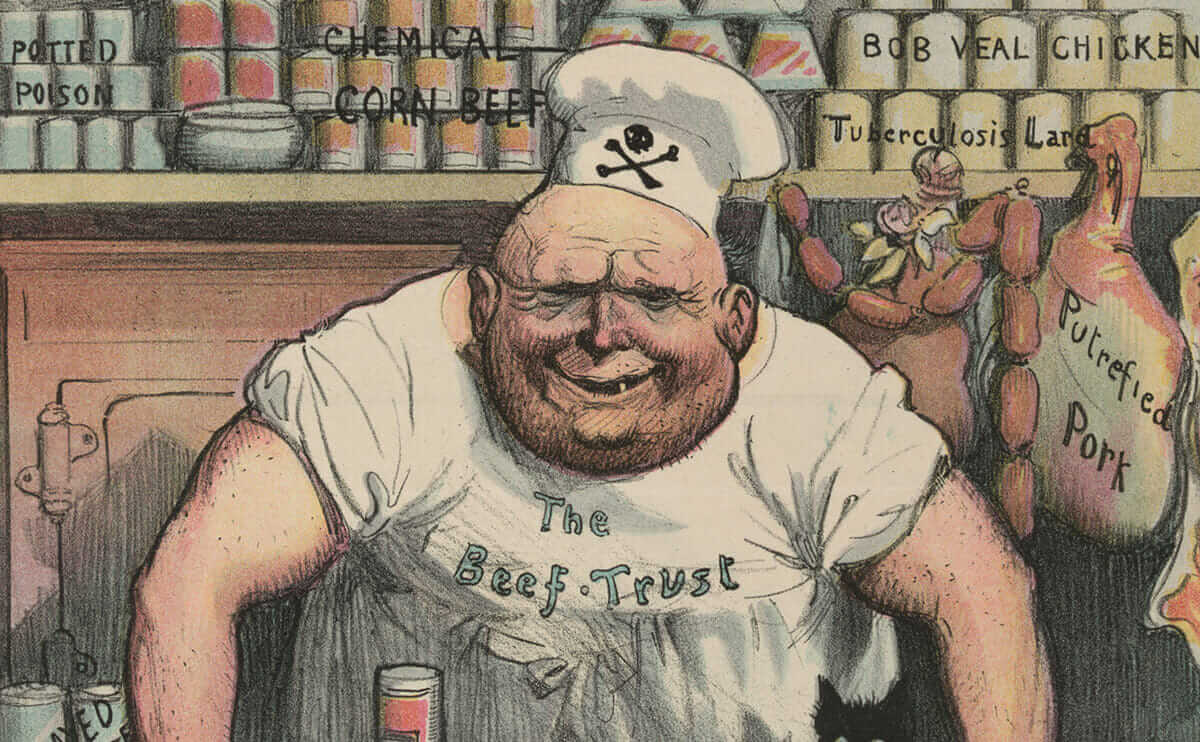

“The Jungle,” published in 1906, was intended to throw light onto the deplorable living and working conditions of America’s immigrants, but instead it became a sensation for exposing the unsanitary conditions of Chicago’s meatpacking plants. Sinclair’s stomach-churning descriptions of the industry’s practices stuck in reader’s minds more than the storyline of a Lithuanian man and his family trying to survive under the harsh conditions typical of the era.

“I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach,” Sinclair would later say. “I realized with bitterness that I had been made into a ‘celebrity,’ not because the public cared anything about the workers, but simply because the public did not want to eat tubercular beef.”

Many of the descriptions of industry practices, which included allowing meat to be stored in rooms where water would drip over it and rats would defecate in great mounds upon it, came from Sinclair’s first hand experience. Before writing the novel he had spent seven weeks working undercover at a plant for a series of articles for a socialist newspaper.

Roosevelt, who had fought in the Spanish-American War before becoming U.S. president, had been forced to eat some of the “embalmed beef” and believed it to be tainted. He was also disgusted by Sinclair’s description of the meat packing industry’s practices and looked further into the author’s allegations. A report by Labor Commissioner Charles Neill and a social worker named James Reynolds, who Roosevelt had sent to inspect Chicago’s meat packing plants, confirmed most of Sinclair’s claims.

Roosevelt pushed Congress to act, and in 1906 the Pure Food and Drug Act as well as the Meat Inspection Act became law, forever changing the way America dealt with its food.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Andrew Amelinckx, Modern Farmer

November 8, 2013

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

If I can write like you, then I will be very happy, but I can’t write like you, where is my luck, in fact people like you are an example for the world. You have written this comment very beautifully, I am very glad that I thank you from the bottom of my heart. anupatel

If I can write like you, then I would be very happy, but where is my luck like this, really people like you are an example for the world. You have written this comment with great beauty, I am really glad I thank you from my heart.