Why Goats Feasting on Rat Urine Makes Sense

A scientist studying goats noticed something odd: goats that ate rat urine were actually healthier than those that didn’t. The science behind why goats (and us) eat what we eat.

Why Goats Feasting on Rat Urine Makes Sense

A scientist studying goats noticed something odd: goats that ate rat urine were actually healthier than those that didn’t. The science behind why goats (and us) eat what we eat.

In the mid 1970s, Fred Provenza, a young wildlife biology researcher, spent the winter watching – indeed, living amongst – herds of Angora goats in Cactus Flats, Utah, northwest of Gunlock. What he learned from spending time with those goats has gone a long way into figuring out how all animals make food choices.

The herds were divided into different-sized plots of blackbrush, a woody desert plant low in protein and lots of bitter tannins. Goats on the two-hectare plot appeared to be losing less weight than another herd on four hectares, with double the land to forage. The results made no sense until he saw one goat on the small plot – the Einstein of the herd – eating the small dwellings of some wood rats (otherwise known as packrats, for their propensity to collect keys and other shiny objects.) The rats used the house as a latrine and, he suspected, goats ate cakes of urine-soaked vegetation as a kind of antacid to diminish the ill effects of eating blackbrush. Rodent urine isn’t usually part of a goat’s diet but the entire herd was soon munching on packrat bathrooms.

Storybook wisdom might suggest these goats were bored or, perhaps, just goats being goats. But Provenza saw something else: A culture learning to self-medicate. And, for more than four decades, Provenza, now professor emeritus at Utah State University, has tested theories about how animals learned how to eat. He’s found, for example, that lambs begin developing flavor preferences in utero based on their mother’s grazing (shown in humans too!). When a nausea-inducing compound was fed directly into the stomach of anesthetized sheep and orphaned lambs, they felt sick and learned to avoid whatever food they had eaten immediately beforehand. (“Conditioned taste aversion” can also occur when chemo patients who associate the nauseating side effects of a drug with certain flavors or odors.) Similarly, a preference for grape or cherry flavors could artificially be reinforced if nutrients were injected directly into an animal’s stomach.

Provenza’s work helped overturn the more mechanistic view of herbivores as eating machines executing innate behavior. “Behavior’s not set in stone by God or anyone else. It’s learned. What you learn, it influences what you become whether you’re a cow, elk, or human,” he says.

As such, taste can be used as a tool for farmers: Teach goats to graze on weeds and, perhaps, they’ll eradicate unwanted plants. Wean cattle off plants growing in stream banks and, perhaps, they’ll be less likely to damage riparian zones. To this end, in 2001, he set up a group called BEHAVE, Behavioral Education for Human, Animal, Vegetation and Ecosystem Management, with a $4.5 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The result are subtle and intriguing. Take Agee Smith, a rancher in Wells, Nevada, who worked with Chuck Peterson, one of Provenza’s students, to persuade a portion of his cows to eat sagebrush. Sagebrush dominates the western United States, a monoculture that arose from the lack of seasonal fires and spring grazing. While the plant might make an animal sick, it won’t kill them. “They’ll eat some sagebrush and think, ‘God, I’ll never touch that stuff again,’” Smith says. “But if you teach them to eat it at a certain time of the year, then the plant becomes a good source of protein. Economically, that can make a huge difference.” In a two-year trial, his herd lost less weight in the winter and helped him save money on supplemental hay. Learning to eat sagebrush might eventually improve biodiversity, Provenza says. “Whether you’re a sage grouse or a pygmy rabbit or any of the number of different bird species, they can’t live on just sagebrush.”

In another dissertation, Dax Mangus, another student, looked at “welfare” elks in Utah, fed supplemental hay in the winter – a great cost to ranchers and a potential vector for disease. To disperse the animals, ranchers grazed cattle in the spring on areas where they wanted wild elk to be in the winter, luring them with plant growth – and also by placing molasses-mineral block supplements. Today, Provenza says, those elk have little or no experience eating hay. Their culture changed.

Breaking the learned habits isn’t easy whether it’s kids eating junk food or an entire herd of goats munching on “antacid” rat latrines. Provenza, now retired, lives in South Park, Colorado with 14,000-foot peaks to his north. He spoke with me one windy day last year. Taste, he said, was a powerful tool and he had seen its potential to change a place. “This is tough country, but for animal that was born and raised here – the deer and the elk and the badgers and pocket gophers and on and on and on – this is home. They’re adapted to it. Play that out over generations and animals come into sync with landscape.”

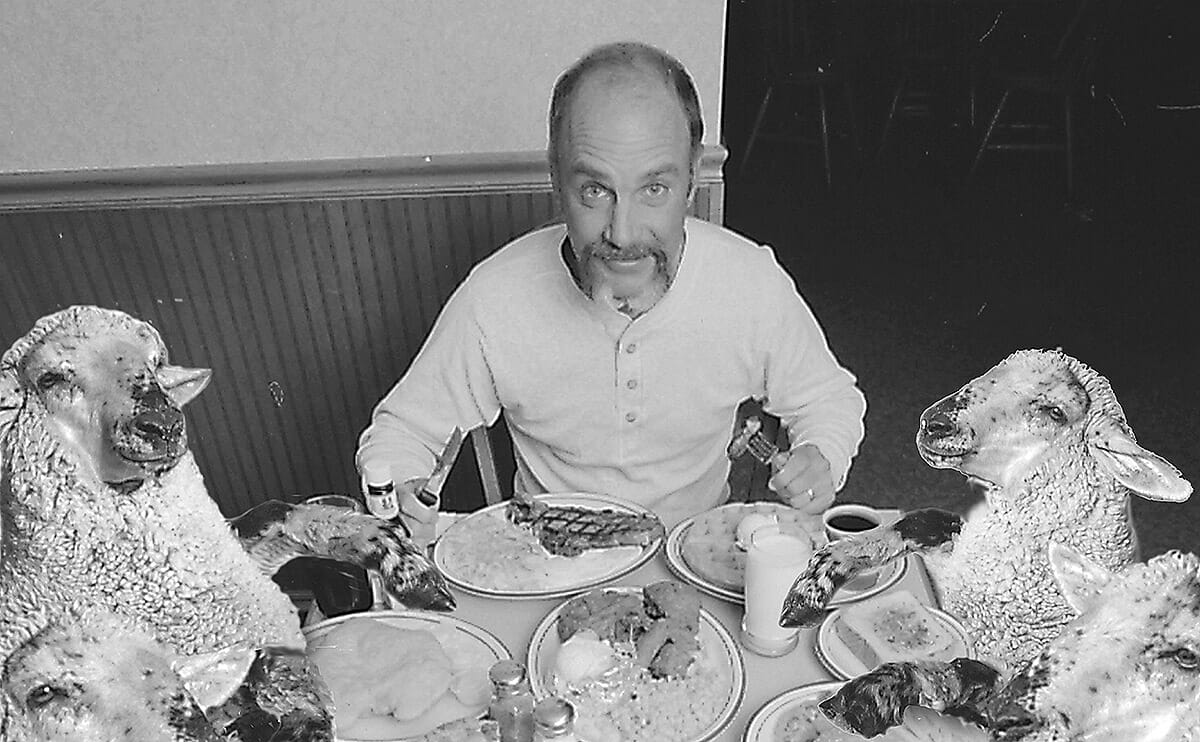

Image at top courtesy of Fred Provenza. And yes, we know they are sheep.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Peter Andrey Smith, Modern Farmer

September 19, 2013

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.