Love eating chicken? Hate the idea of factory farming? Want to do something about it? Ali Berlow is here to help. Several years ago, Berlow, a food writer and activist who lives on Martha’s Vineyard with her husband and two sons, faced just such a quandary. But instead of becoming a vegetarian, Berlow took a […]

Love eating chicken? Hate the idea of factory farming? Want to do something about it? Ali Berlow is here to help.

Several years ago, Berlow, a food writer and activist who lives on Martha’s Vineyard with her husband and two sons, faced just such a quandary. But instead of becoming a vegetarian, Berlow took a more radical and yet surprisingly simple path: together with members of her community, she created a mobile poultry processing trailer, or MPPT, that travels directly to farmers and backyard breeders.

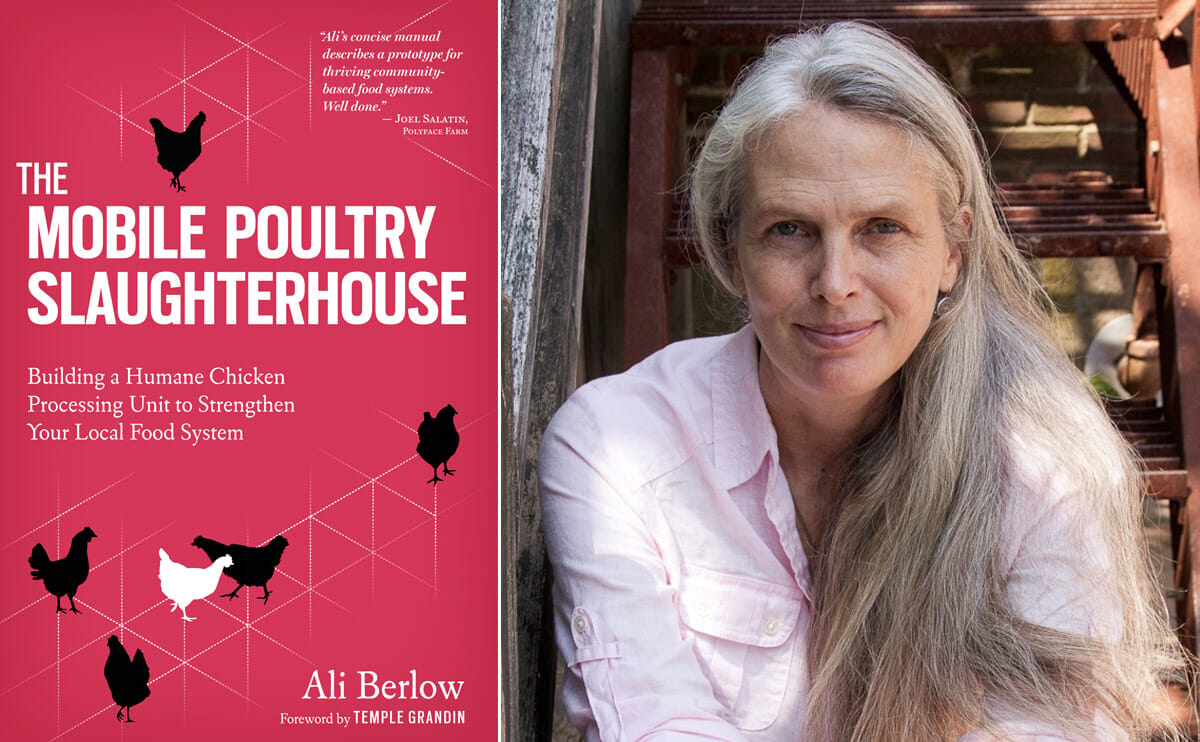

Berlow, who is also the founder of Island Grown Initiative, a non-profit organization working to create a more sustainable agricultural system, recently published The Mobile Poultry Slaughterhouse, an extremely practical book detailing her own experience and offering a wealth of advice to those who wish to follow in her path. It contains everything from permitting information and how-to diagrams of chicken slaughter to cease and desist letters and a guide to building a double-sided hot and cold water sink. We spoke with Berlow about her book, the challenges of getting a MPPT up and running, and how to talk to just about anybody about chicken slaughter.

Modern Farmer: I love the title of your book: it’s very straightforward.

Ali Berlow: It’s the book you don’t know you want to read. One thing I love about Storey Publishing is they just nail it; this is what it is. You can’t shy away from the words; you have to bring it on.

MF: And that’s something you come back to repeatedly in the book: a lot of people don’t want to talk about, much less acknowledge slaughter.

AB: It’s an uncomfortable topic, but that doesn’t mean we can’t embrace it, and I think we should as transparently and ethically and humanely as we can. Temple Grandin [whom Berlow met in the process of bringing the slaughter unit to fruition] has been a huge proponent of it forever. We’ve established an awareness of a higher quality of meat, and yet we still need more [humane] slaughterhouses. The mobile unit is literally transparent: it pops up and is gone the next day. I think humane slaughter is the missing piece; you can do all the right things in raising and butchering an animal but you still have this one moment.

MF: In the book, you write about getting resistance to the idea of the MPPT. How did you deal with opposition and misconceptions?

AB: I think it’s really about meeting people where they’re at, and also meeting the community where they’re at. If you’re talking to the board of health, what do they want to hear? If you’re in the grocery store with someone who says, “Just give me a boneless, skinless breast,” how do you meet them? I’m a mom, and my activism and this project was about getting better food for my family. Once I became aware of the meat industry – we eat a ton of chicken, and it’s supposed to be healthy and more affordable – but you start to look behind curtain and ask, How do I get best food for my family? How can I help to make this problem better? But yeah, with slaughter I think a lot of it is education. If someone’s looking at a whole bird, which does remind them it’s an animal, we always got past that by having a poultry-cooking component in our workshops. It was about not being judgmental and saying, “O.K., let’s cook something with bones in it.” Again, you have to meet people where they’re at and have conversations about humane slaughter and why this is important. You’ve got to stand your ground in a respectful way.

MF: Until it’s not such a radical concept anymore.

AB: What impressed me was maybe six or nine months ago I was talking to a farmer and he said, “People don’t even think about this anymore.” I was taken aback. I was, like, have you seen how much gray hair I have? I’m not even 50 yet! But then I was like, wow, that is truly the success of it: they’re not even talking about it anymore. And wow, what a great place to be. The [slaughter] schedule works, people are getting chicken, the farmers are out there, the animals are living a great life. You don’t want to take it for granted but it was such a cool thing to realize.

MF: How difficult was it to cut through all of the bureaucracy involved in the process of getting the unit up and running?

AB: It was outside of the normal regulatory box. Once we had the support of the state of Massachusetts, it was three agencies that had a say: the departments of agriculture, public health, and environmental protection. There was a scalability problem: the regulations are written for a large brick and mortar facility. So we said yes, it’s outside of the regulatory box, but look at the box that’s been painted. So how do we scale it to make it work? But also you also can’t stop people from wanting good, healthy, pastured chicken. It’s going to happen, so how do we make it happen together? So it took a little bit more effort. But don’t all new innovations start that way?

MF: In the book, you advise not letting early group discussions turn into bitch sessions. This sounds like it would be difficult.

AB: A lot of the points are valid. You have to hear what they really say. I think when you involve the community in discussions of something that can be volatile, you’ve got to let it go to that point where everybody’s being heard. It’s not enough to just have a community meeting; you’ve got to show up and do something, and if it’s not working you have to change your strategy as an activist. You can’t promise things you can’t deliver. You have to be ethical, and, as Patti Smith says, keep a good name. And keep your phone charged.

This is a great story, but the story has to be told in its entirety. I remember someplace called [the mobile slaughterhouse] a chicken killing machine. I was like, oh, come on, do we have to go there? It’s not a machine. It doesn’t kill anything. The stainless steel equipment is only as good as the people who operate it, and the person who dispatches the chicken. With all due respect, I felt that was someone’s discomfort with the topic. It’s how we marginalize the messy parts. I’m like, let’s not marginalize it. The messy part is way too important.

MF: There were obviously a lot of obstacles in getting the mobile slaughterhouse off the ground, but what would you say the biggest challenge was?

AB: I think as with any project we get ourselves into, we don’t always realize how big it is. I think I would say to anyone building one of these things is give yourself time to build it. It shouldn’t be instant; it’s not an easy thing and needs to take time and planning. So my challenge was there wasn’t really a model to follow. I think it took three years to get the first permit. I guess I can’t tell you one specific thing other than time and planning and standing strong in the face of adversity. And also to that end, one thing I think about in the food movement is the language that we use and how we work to create healthy change. [People within the big food system] are not bad people. This isn’t about war; they’re not bad farmers or bad people or bad regulatory agents.

MF: You write that, “… any good and humane slaughter system… is only as good as the people involved.” Was it difficult to find good people at first?

AB: Getting the people at the beginning was difficult because it was a new venture. We did reach out to the Brazilian community because culturally, they are more connected to their food than Americans, and they were awesome. The challenge at first was that it was small and wasn’t immediately operating seven days a week. Now that it’s been in operation for a few years and people aren’t even thinking about it, it’s not hard to find a chicken crew because it’s been accepted. The crew is an entry-level skilled job, and now people are aware that, ‘Oh yeah, I could work on a chicken crew.’ It’s not a difficult job to fill anymore.

MF: Today, how many farmers are using the mobile slaughterhouse?

AB: As far as I know, there’s four farmers that are under the community umbrella license, meaning they can sell to farmers markets and restaurants. And then there are a number of backyard growers. And what’s also happening is that some of the farmers that started using and booking the trailer have become successful enough in raising more birds that they have started to build their own parts of an abattoir, so they might just rent out our scalder or plucker. So they’ve kind of graduated, and that’s what the goal is: you have some graduating classes and some backyard farmers who very well may become next year’s.

MF: Are you getting inquiries from people who want to start their own slaughterhouses?

AB: Early on we had inquiries of, ‘Hey, can’t you bring this over to the Cape?’ The message, I think, is come see it and then go build one and make it work for your community. I hope people are inspired by the project and book and success to be curious, and then know it’s not a cookie cutter thing. I can’t say enough really about it in terms of size, appropriate technology, and that it works with regulators. It’s pretty amazing and at the same time it’s really simple: it’s like, yep, there’s really good stainless steel and really good people and then look at what’s for dinner.

MF: Critics like to say that small-scale slaughterhouses will never present an alternative to factory farms in a way that makes them viable to communities and farmers around the country.

AB: I think it is viable. The consolidations of slaughterhouses across country have made them few and far between. It affects how few animals people really are raising because if they don’t have access to a slaughterhouse it’s really a dead end. We had that happen; if we built it, they grew it. It increases production right away. Each community and geographic area may have different concerns to address, but they can be addressed with good communication and transparency, and the alternative – I mean, there’s really not an alternative. Either you’re killing chickens poorly and not in a food-safe manner, or you’re not raising chickens because you don’t have access to a slaughterhouse. And then there’s demand increasing from consumers who are being educated and versed from things like Modern Farmer. So yeah, I think this is totally viable.