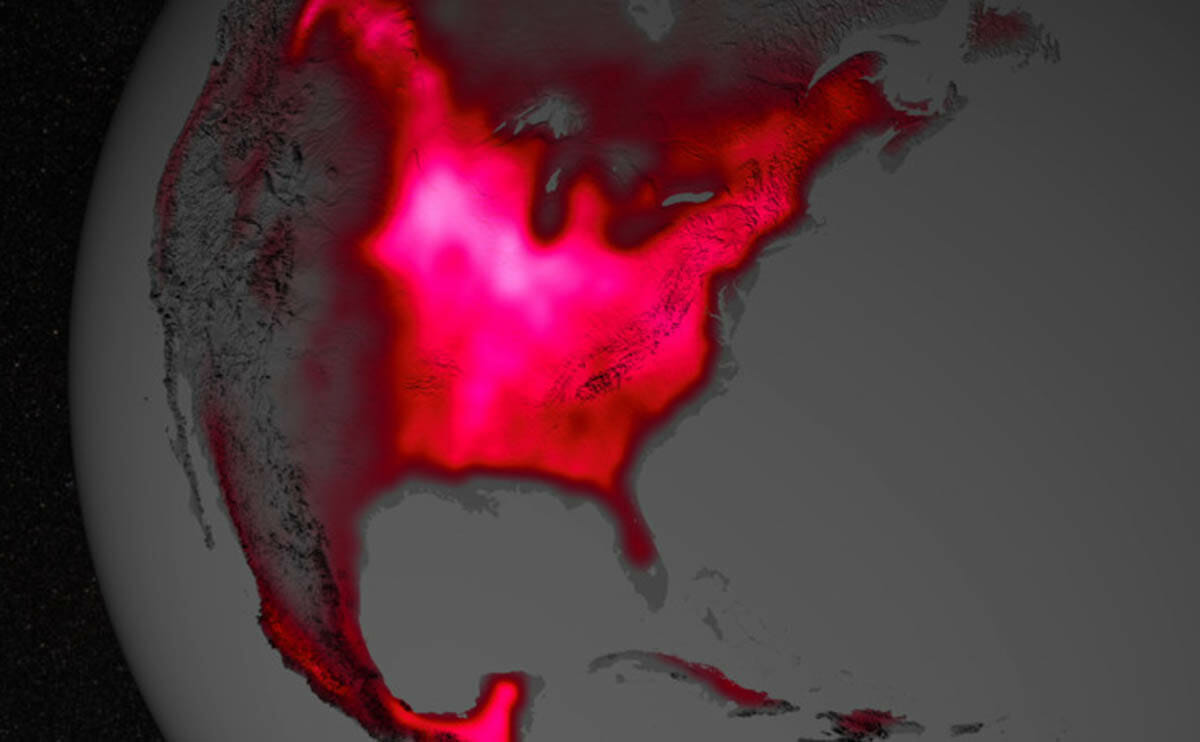

In the height of the growing season, the Corn Belt lights up on NASA's maps of photosynthetic activity like a Christmas tree.

Productivity is a tricky term here. Often, agricultural productivity describes how much food a farmer produces with a limited number of resources. The research, published on March 25 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, is instead concerned with “gross productivity” — in other words, the sheer amount of photosynthetic activity happening in a region.

To get a read on the metric, researchers led by Joanna Joiner of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center looked to the basics of photosynthesis. Chlorophyll in plants mainly absorbs light for conversion into energy, but the cell organs also emit a small portion of that light as a florescent glow invisible to the naked eye.

Joiner’s team realized they could measure that glow from existing satellite data. Research led by Luis Guanter at the Freie UniversitÁ¤t Berlin then used the data to estimate the photosynthesis from agriculture.

As you might expect, the tropics topped out productivity during most the year, but then there was the raging plant party known as Iowa in July. In the height of the growing season, the Corn Belt lit up NASA’s map at levels 40 times greater than those observed in the Amazon rain forest.

“The paper shows that fluorescence is a much better proxy for agricultural productivity than anything we’ve had before,” said Christian Frankenberg, a co-author of the paper at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in NASA’s press release. “This can go a long way regarding monitoring ”“ and maybe even predicting ”“ regional crop yields.”

As you might expect, the tropics topped out productivity during most the year, but then there was the raging plant party known as Iowa in July. In the height of the growing season, the Corn Belt lit up NASA’s map at levels 40 times greater than those observed in the Amazon rain forest.

Getting there probably will take a satellite designed in part for the purpose of measuring crop productivity.

For the their latest study, NASA relied on data from Metop-A, a European weather satellite. NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2), scheduled for launch this coming July, would be able to measure plant florescence at a higher resolution than current orbiting instruments. NASA’s Soil Moisture Active Passive satellite, set for launch after OCO-2, would complement the effort.

From there, researchers could expand their analysis to landscapes of greater crop diversity than the central U.S. After all, not all places on the planet live on corn alone and different plants transmit different wave lengths of light. As the world tries to feed a hungrier population in a warmer world, productivity data from remote sensors in satellites could help inform both markets and policy.

But in the short term, the study from NASA might be of most interest to scientists studying global climate change. Joiner’s team found the Corn Belt to be 40 to 60 percent more productive than estimated in current climate models. Unlike wild plants, crops have frequent access to nutrients and irrigation, which has made it difficult for scientists to estimate their impact on the global carbon cycle in the past. The pink blotches in NASA’s imagery means U.S. crops are taking more greenhouses gases from the atmosphere than previously thought.

To be clear, that doesn’t mean corn farmers are secret warriors against climate change. Corn farmers might actually be the first to balk at the idea given the skepticism with which they view climate scientists. And agriculture — especially when reliant on nitrogen-based fertilizers — remains one of the key drivers of global climate change.

But, whether or not corn farmers trust them, climate scientists will need to acknowledge that the Corn Belt growers are pretty darn good at turning airborne carbon into solid vegetation.

[mf_video type=”youtube” id=”WokPomQwfS0″]

There seems to be a bit of confusion as to whether the corn belt in general grows all corn but doesn’t differentiate as to how much of the map is also growing wheat since the growing area encompasses areas of wheat and corn, and of course wheat is consumed by humans and “corn” is used as feed for farm animals

From the above article — “The Corn Belt lit up NASA’s map at levels 40 times greater than those observed in the Amazon rain forest.” The NASA press release linked to in the article itself says 40 PERCENT, not 40 times: “fluorescence from the Corn Belt, which extends from Ohio to Nebraska and Kansas, peaks in July at levels 40 percent greater than those observed in the Amazon.” That’s a rather HUGE ERROR in reporting.

“And agriculture — especially when reliant on nitrogen-based fertilizers — remains one of the key drivers of global climate change.” This is a false statement. The Sun is the key driver of climate change. Agriculture is statistically significant.