How China Became the World’s Largest Pork Producer

China’s “pork miracle” means that over half of the world’s pigs now live in China.

How China Became the World’s Largest Pork Producer

China’s “pork miracle” means that over half of the world’s pigs now live in China.

The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP) released a report last month documenting the causes and the consequences of the pork miracle. The story sounds simple: In the last few decades, China has developed the world’s largest pork industry to feed a rising middle class.

But the specifics of the story are nothing short of astounding.

As China’s pig population continues to increase, the country’s total meat production is expected to reach to 93 million tons by the end of the decade. Higher growth rates of chicken and beef will drive much of that increase, but by 2022 pork will remain emperor of China, accounting for 63 percent of production in retail weight.

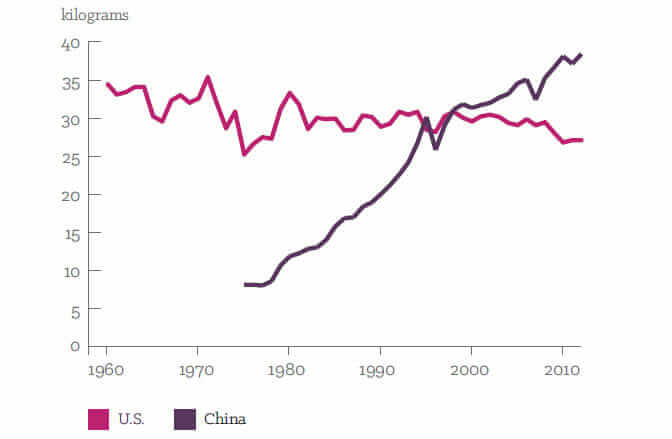

A quickly rising appetite for pork in China has fueled the sudden jump in production. In the mid-1970s, in the midst of the country’s Green Revolution, an average Chinese citizen ate an average of 8 kilograms of pork a year. Today, each person in China eats about 39 kilograms of pork a year, while Americans eat about 27 kilograms.

While weight might be the easiest way to account for the sheer amount of meat, consider the porcine population. In 2014, swine production in China will reach 723 million head. Just to be clear, that’s more than twice the U.S. population and half the Chinese population.

The IATP looked to Chinese history to track the causes of the country’s pork explosion. Apparently, pig husbandry isn’t just woven into 6,000 to 10,000 years of the country’s past — it’s an everyday part of the Chinese language. In Mandarin, the general word for “meat” (rou) is the same as the specific word for “pork.” Early Chinese speakers also made the character for home and family (jia) by adding the roof radical to the pig radical. So, in a figurative sense, a roof over a pig makes a home.

The tradition of pig rearing in China helps explain the linguistic connection. For thousands of years, single households valued pigs not for their meat as much as their ability to turn waste into fertilizer. But as pork was the go-to meat for celebrations, the meat also become a marker of wealth.

The IATP argues that the Chinese government’s push to make pork cheaper serves two joint purposes — it meets the desire of the population and demonstrates the new wealth of the nation against former scarcity.

When it comes to pork, China doesn’t stop at the tenderloins. Feet, liver, kidney, stomach, spleen and other body parts can all make a welcome addition to Chinese dinner plates. The country’s lack of pickiness when it comes to pig parts has helped make it one of the top destinations for the byproducts of meat processing companies worldwide.

Americans fret about prices at the gas pump, so the U.S. government keeps a strategic reserve of petroleum. And because the Chinese people fret about the cost of meat, China keeps a strategic reserve of frozen pork and living pigs.

The government built the reserve following a fatal outbreak of PRRS (also known as porcine blue-ear disease) in 2006 that left millions of pigs dead and pork prices through the roof. The idea, like with other strategic reserves, is to regulate the price of the meat by buying pork when the price climbs too high and releasing pork to the market when the prices fall too low.

Last year, Rabobank senior analyst Chenjun Pan told CNBC it would be difficult — maybe even impossible — to build a reserve big enough to manage price fluctuations in the massive Chinese pork industry. But nevertheless, the government has built a staggering collection of pens and freezers to help ensure more meat ends up on plates of Chinese citizens climbing into the middle class.

What is a government to do when its enormous pig population doesn’t stack up in genetic quality? Obvious: call the British and arrange an annual subscription for their finest array of piggy semen. As the Guardian first pointed out, Britain now flies loads of pig loads, both fresh and frozen, to China as a part of the arrangement.

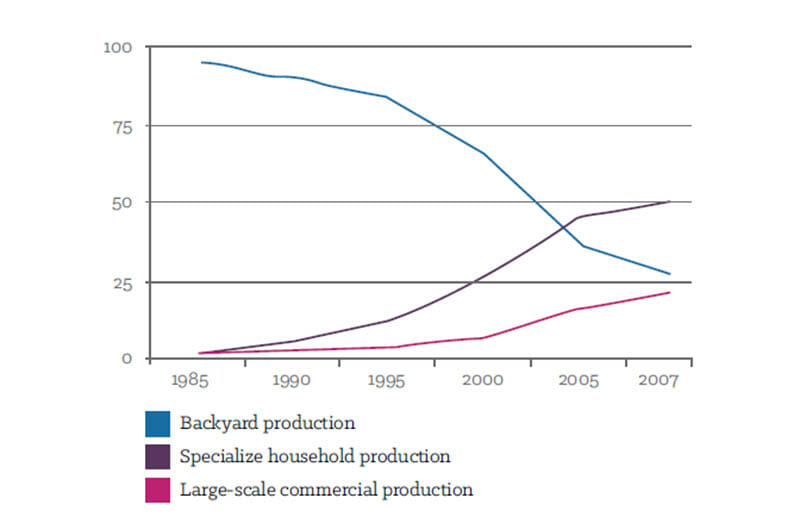

Just as staggering as the rise of the Chinese pork industry is the speed at which it has embraced industrial pig farming. The number of hog farms dropped 70 percent between 1991 to 2009. Over the same period, the average hog farm grew from 945 head to 8,389 head.

As the Chinese government has helped finance the rapid consolidation, Chinese firms have gone abroad to learn how to run them. Last year’s merger of Shuangui and Smithfield not only brought one of the largest U.S. pork operations under Chinese control — it gave Shuangui new insight into the methods of industrial pig rearing in the U.S.

But the IATP doesn’t lay the blame on China for copping American know-how.

Instead, they point to a global trend of agribusinesses pigging out beyond their borders, growing ever more consolidated and industrial in the process.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Sam Brasch, Modern Farmer

March 11, 2014

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

hope Africa can do same

my name is lin geng fu

There doesn’t seem to be much interest in this item. I worked in China for a short time on a joint venture farm in the late 1980s. A very interesting time in the early years of development in the commercial pig production.