The Art and Science of Muskrat Cooking

Do you have what it takes to win a rodent cooking competition? One man’s journey into a most unusual culinary challenge.

I live in Washington, D.C. This is the seat of the American federal government, the regulatory jungle of power and money, and yet so easily we forget that this is a city tucked into a rich estuary known as the Chesapeake Bay. We Washingtonians gaze at the larger nation through economic, political and social abstractions, so much so that we forget where we are; the ecosystem of the Chesapeake Bay is barely an afterthought to the hallowed water in the Reflecting Pool, the imported cherry blossoms illuminating the Tidal Basin each Spring and the giant pandas frolicking at the Smithsonian Zoo. We imagine the world beyond the Beltway simply as a collection of other cities reachable from D.C., but the interstitial space rarely even registers on our radar.

We all live in some kind of a bubble. This is ours.

From my gentrified perch in a renovated Columbia Heights row house, I recently stumbled upon an episode of “Bizarre Foods” with Andrew Zimmern that profiled the Baltimore and the Chesapeake Bay region. The first segment of the show took Zimmern to Dorchester County, a lesser-known county situated on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where he met a local family who cherishes the bounty brought by the humble muskrat. During the colder months, these muskrats are trapped in the swamps and brackish water of the Chesapeake Bay where locals sell their pelts in an international commodity fur market. The meat, however, is consumed locally, and there, as chronicled by Mr. Zimmern, it is consumed with gusto. These muskrat traditions culminate annually in a festival that features competitive muskrat skinning and, of course, a beauty pageant.

More to the point, what is a muskrat? And how does it compare to the cultural touchstones of beef, chicken and pork?

While I had traveled across the Bay Bridge to Maryland’s Eastern Shore before, never had I been that far south. Could this be real? It seemed so: A colleague of mine lives in Easton, Maryland, and told me this community indeed existed south of the Choptank River, a bluecrab-rich river that washes into Dorchester County from the Chesapeake Bay and serves as a dividing line between the past and the present. Admitting that he had never traveled that far south but that he had in fact tasted muskrat, my colleague warned me that muskrat was the only thing he’s ever eaten that made him vomit.

Not being one to shy away from a good challenge, my journey into muskrat cuisine – and the National Outdoor Show, the beating heart of muskrat culture – began.

My dad is from Hong Kong. Perhaps it goes without saying that Cantonese culinary traditions keep me honest about how “exotic” a muskrat can actually be. I also grew up in North Carolina, preoccupied in my youth with the hunting and fishing cultures taking place from the Outer Banks to the Appalachian Mountains. If ever there were an Asian American with a serious identity crisis, it’s me.

But the notion of “food” is perhaps just as fluid, if not more so, than the confusing identity baggage I drag to each meal I consume. More to the point, what is a muskrat and how does it compare to the cultural touchstones of beef, chicken and pork? It turns out that the epicenter of the Dorchester County muskrat culture explodes in late February of each year. Being well within that blast radius, I cleared the weekend of February 22 for a day trip to the 2014 National Outdoor Show held in Golden Hill, Maryland, at the South Dorchester School. I learned from their spartan website that the schedule of events begins with a beauty pageant Friday evening and ends late on Saturday after a series of timed muskrat, raccoon and nutria skinning contests. Above all, food would be served — including locally harvested oysters and “‘rat,” the sobriquet given to the muskrat of Dorchester County. Moreover, the show boasts an annual ‘rat cooking competition that I wanted to see.

But something else caught my attention.

The muskrat cooking contest was open to anyone — and the contest rules were liberal. My mind raced. While I was committed to eating a rodent in two weeks time, I wondered if I could pull together a dish worthy of entry into their contest. I felt like this was my chance to prove something I’ve always wanted to prove: That in the right hands, most food can be controlled and rendered into something elegant. In short, I wanted to prove that the notion of eating muskrat is no more deserving of a wrinkled nose than the notion of eating a pig. But first, I had to find one.

Two weeks before competition day, I bought nine frozen muskrats from the bowels of a seafood shop in downtown Baltimore. Needless to say, the fishmonger gave me a long once-over as he handed me a trashbag heavy with frozen muskrats. He confirmed that they were already cleaned, musk glands already removed. When I got home, I un-sleeved one of the frozen muskrats from its plastic bag. Bloody flecks of ice littered my sink as I revealed a stiff, rabbit-sized animal in my bare hands. This isn’t like bringing home meat from the grocery store. There is no stamp from the USDA existing between you and this eviscerated animal carcass thawing in your kitchen. It grimaces at you from its bare eye sockets, and two scaly claws and two scaly feet remain attached, clenched and pulled up against its body. Skinned animals, particularly mammals, look especially menacing and ugly once flayed, and this bucktoothed muskrat jeered at me as though he were threatening to chew my ear off.

This isn’t like bringing home meat from the grocery store. There is no stamp from the USDA, existing between you and this eviscerated animal carcass thawing in your kitchen.

An unusual scent, deep and fishy, wafted from the dead rodents. Despite my specimens lacking musk glands, they still smelled. The mere removal of these glands is likely as effective as thrice washing chitterlings ”“ there’s always a hint of God’s intent left behind. Lying listlessly in the sink, my kitchen seemed to warm a few degrees, and the muskrat perfumed the air with a bouquet of swamp: I detected notes of large mosquito, algae and bullfrog. I needed to have a beer first. Some calf stretches and a few arm-circles later, I was ready to confront this animal.

My research indicated that I needed to try to rid the uncooked carcass of this pungent smell before attempting to cook it. This meant leeching lingering blood and trimming excess fat from the meat. Surely, I thought, my experience with various Chinese cooking techniques prepared me somewhat to disarm various animal proteins before cooking. For instance, one can mitigate the muddy taste of catfish by soaking the meat in a solution of salt, rice wine and ginger first. Baking soda can help with certain cuts of beef or offal and also tenderize. Milk can temper the urea in shark meat. How bad could this be?

I approached my first ‘rat as if it were a catfish pulled from a muddy river bottom. I submerged the little ghoul into a steel bowl filled with two-thirds of a bottle of Shaoxing wine, two large, crushed knobs of fresh ginger and about a liter of salted water. As I covered the bowl with plastic wrap, I scoffed with conquest, and placed the bowl in the refrigerator. I believed my kung fu was strong. An hour later, I took the bowl out of the refrigerator to inspect the drunken ‘rat. But as I peeled back the plastic wrap, I was greeted with a roundhouse kick to the nose of bloody rice wine and swamp. The liquid around the ‘rat had thickened and the red mess pooled in the bowl. Gagging, I poured the marinating solution down the sink.

ven, then, I was confident. The contents going down the sink were so vile I thought I must have succeeded at beating the funk out of the small carcass.

To test my now-purified meat, I thought I would butcher the ‘rat as if it were a rabbit. With my cleaver, I first chopped off its little paws and feet, and arranged them into a pile on the side. When I went to remove its arms at the shoulder joint, I noticed how dark the meat was still ”“ the blood was stubbornly encased in the muscle fibers. I thought back to what I poured down the sink, and forged ahead cavalierly, removing its thighs, slicing off the long skin flaps, discarding the rib cage and leaving only the small loin section left on my cutting board. Weird, I thought, the ‘rat was still bleeding. Impatient, I endeavored to delicately debone the spine from the loin like I was some sort of neurosurgeon. The resulting loin was about the size of a Post-It note.

Now it was time to see what this meat could handle. Pressing it between a sheet of plastic wrap, I pounded out the loin into a thin disk. The response was unremarkable; it flattened out without too much effort, like any lean cut. I seasoned it with salt and pepper, dusted it in flour and rolled it in panko breadcrumbs to pan fry. Again, unremarkable, as the result was a crispy, Milanese-y disk of pan-fried meat. A few cautious sniffs later, I took a nervous bite.

The bite was crisp with a tender, meaty touch in the middle. And then the unmistakable flavor of the muskrat chimed in. It’s an indelible flavor of a stagnating tidal estuary ”“ a little fishy, a hint of metal, followed by that weird smell found at the bottom of a bag of forgotten spinach. The experienced may call it earthy. The uninitiated may call it nauseating. I found it utterly frustrating, and so I called it quits for the weekend, and resolved to do more research before my next attempt. I only had eight muskrats and change remaining.

I took a few notes that week. Among them, to change the soaking liquid as often as possible within a longer period of soaking time. I also thought that I needed to put the ‘rat in something stronger than rice wine, and to maintain a high salt content to draw out the blood in the meat. Finally, I didn’t have any confidence that butchering the ‘rat after soaking conferred any great benefit. Rather, I would follow an approach to soak, then boil the ‘rat in a second cleansing solution, then fork the meat off the bone.

On Valentine’s Day, one week before the contest, I spent a romantic evening drawing a bath for three muskrats.

On Valentine’s Day, one week before the contest, I spent a romantic evening drawing a bath for three muskrats. My idea was that while the salt would serve to draw out as much blood as possible, I would introduce various forms of acids to try to neutralize the flavor remaining in any blood that didn’t come out. The first would be milk-based, proceeding on the theory that the slight acidity in milk could counteract any off-tastes remaining from stale blood in the meat. The second would be vodka-based, a stronger variation on the acid-wash approach, and the third would be straight Coca Cola, proceeding on the theory that the high sodium content plus the carbonic acid in this beverage would deliver a tenderizing, knockout blow. That night, I drowned the ‘rats in their individual baths, with the intention of changing the soaking solution a couple times before trying to cook them the next day.

On Saturday afternoon, after changing the soaking solutions twice, I was ready to boil out any lingering trace of their prior muskrat identities. I reached for the milked muskrat first, and dropped him into a pot of boiling, salted water. Within minutes, my entire house smelled of muskrat. And even though it was below 20 degrees outside, I ran to open windows and doors to fumigate my home with blistering cold air. I ladled off the foamy, dark scum stuck to the crests of the roiling water, and I held my breath as muskrat-infused steam enveloped my face. Within ten minutes of the first boil, I changed the water. Shivering from the cold and letting loose the occasional whimper, I told myself to man up and closed the doors and windows for the cooking phase. I changed the water again after the first hour, and one more time at the next half hour.

It took nearly an hour and half for the meat to soften. Peering into the pot, the muskrat’s head had by this time dislodged itself from its body and was rolling around at the bottom. I placed him in a bowl to cool. I also gave him his head back because this ‘rat earned at least that dignity. Fork tender, the meat easily came off the bone with a firm nudge and as I performed this solemn, albeit gruesome task, I had to pause and pay my respects to a noble adversary: skinned, eviscerated, decapitated and sent to a boiling, watery hell, this muskrat never surrendered. The smell did not abate, and the funky, fishy character of the meat held steadfast as I choked a small piece of its shoulder down.

[mf_mosaic_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/IMG_4830.jpg” caption=”Simmering muskrat, plus head.”]

I was defeated, but undeterred. Two other rats awaited. This experiment could not go on, however, if I had to contend any further with the stench of boiling muskrat and no reasonable form of ventilation available. This time, I added several knobs of crushed, fresh ginger to the boiling liquid. The improvement in smell was dramatic, and my plants came back to life.

Apart from the small victory in mitigating the stench of cooking the muskrats, the Coke-soaked ‘rat and the vodka-soaked ‘rat both showed minimal improvement in terms of smell or flavor or texture. To be sure, the rusty gaminess of the muskrat was diminished by these preparation and cooking methods. But that wasn’t ever the problem. It was that unmistakable fishiness that parried every blow I made and managed to stab me right in the tongue every time. In fairness though, I could work with it under the limited time I had before the contest, a little funky fragrance notwithstanding. More importantly, I wanted to work with it. This was muskrat, after all, not a baked potato.

In order to do so, however, I decided I needed to do two things. First, I needed to “mask the musk” or at least find some way to complement it. Second, I needed to add fat to conduct flavor. A skinned muskrat is especially lean, and a long, slow boil would only further remove any residual fat. The rest seemed to be a matter of aesthetics.

There are a few flavors I’ve worked with in the past that I think do a great job concealing and simultaneously complementing meat. Cumin is one, curry is another, horseradish is another and hoisin sauce is yet another. (Think: grilled, cumin-crusted lamb skewers, curried chicken, prime rib and char siu bao at dim sum.) So I thought I would first attempt to incorporate the muskrat meat into an empanada, relying on the butter in the puff pastry dough for added fat. Second, I would take a stab at a Thai red curry, relying on coconut milk for added fat. Third, I would attempt a sandwich with a horseradish spread, relying on cheese for added fat. And fourth, I would try some yet-undetermined method of using hoisin sauce to flavor the muskrat, relying on bacon for added fat.

During the week, I did a trial run of the dishes I thought I might enter into the competition. Pressed for time, I had little to offer much in the way of an explanation or defense of this project, so I received a number of squeamish rejections to casual invitations to “eat muskrat.” Nevertheless, the empanadas emerged from my oven beautifully, the Thai red curry was lovely, the sandwich was picturesque and though my bacon concoction needed some work, it was almost there. But after each bite made in the service of perfecting these recipes, the novelty of this entire ordeal steadily wore off. I started to hate the taste of the meat I knew was buried in my empanada or suspended in my curry, and I could no longer ascertain whether I was experiencing a physical aversion to it, or a psychological one.

But I also had an epiphany that week. I had been toying with the idea of paying homage to the famed Bacon Explosion somehow by incorporating muskrat into it. Fortuitously, the Bacon Explosion, a monstrous roll of bacon and sausage, is shaped like a log. I figured that if I could work a tail into this log, it could actually look like a muskrat. And, if I plated the mock-muskrat in a dish filled at the bottom with a dark, bourbon-infused sauce, it would actually imitate an intoxicated muskrat swimming in a swamp.

As much as I wanted to see this year’s beauty pageant, I had muskrat dishes to prepare the Friday evening before the competition. I had settled on two other entries in addition to the Bacon ‘Rat, which received special names: “Swampanadas” and “‘Skurry Curry.” The sandwich got canned.

[mf_mosaic_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/IMG_4857.jpg” caption=”Weaving the Bacon ‘Rat topping.”]

All wrapped up, with a sausage tail.

Swampenadas!

The Skurry Curry.

On Saturday, February 22, I prepared my dishes: The rules only permitted cooking competition entrants to reheat dishes on site. After an anxious two-and-a-half hour drive with my cooked muskrats in tow, I reached the town of Golden Hill, Maryland. My brother, who happens to live in Maryland as well, agreed to meet me and a few other curious D.C. folks there.

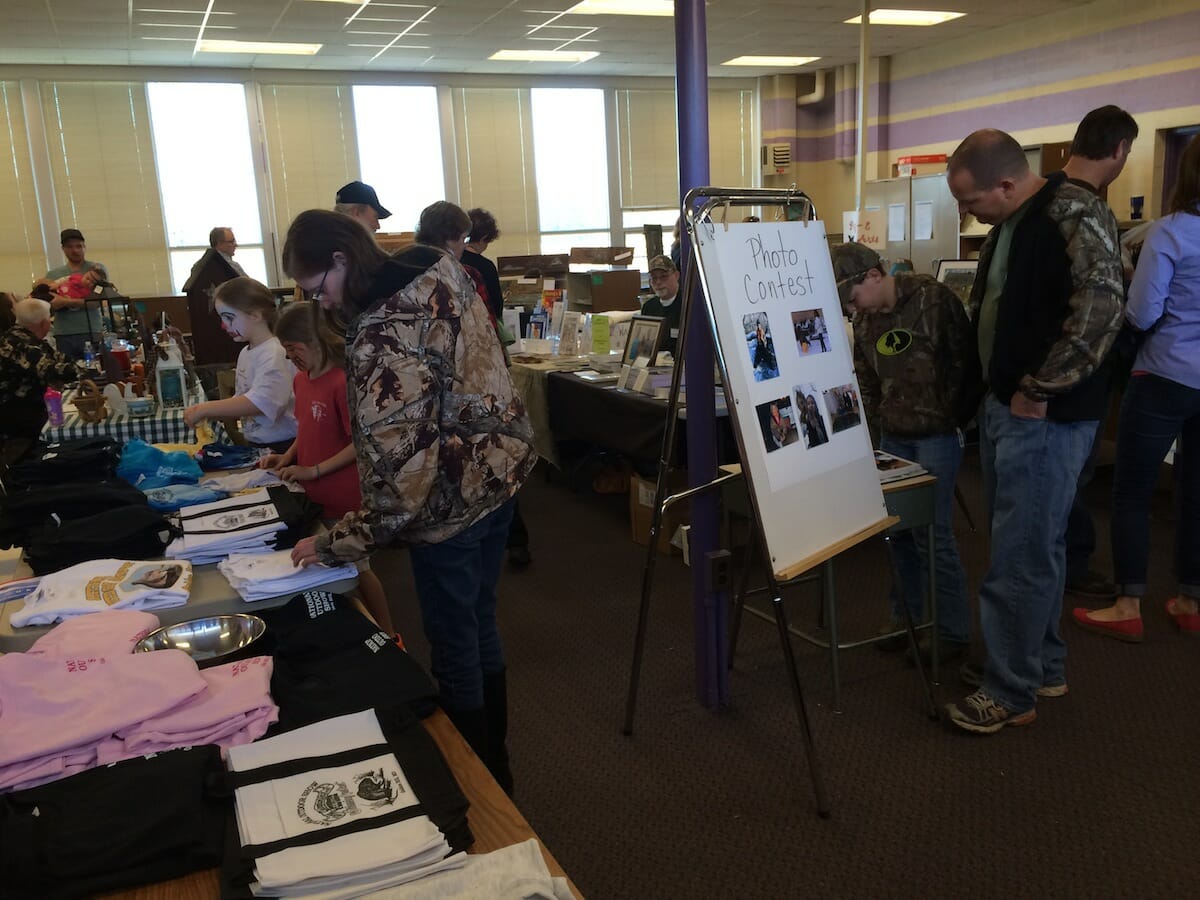

Each year, the National Outdoor Show is hosted in the one-story building of the South Dorchester School. The building houses 200 students an aging, brick and cinderblock structure surrounded on all sides by farmland. But it accommodates over 1,000 show-goers each year for this event and parking is complemented by a shuttle bus system running constantly between the school and a muddy parking lot about 200 yards down the road.

Arriving at the show.

Scenes from the National Outdoor Show.

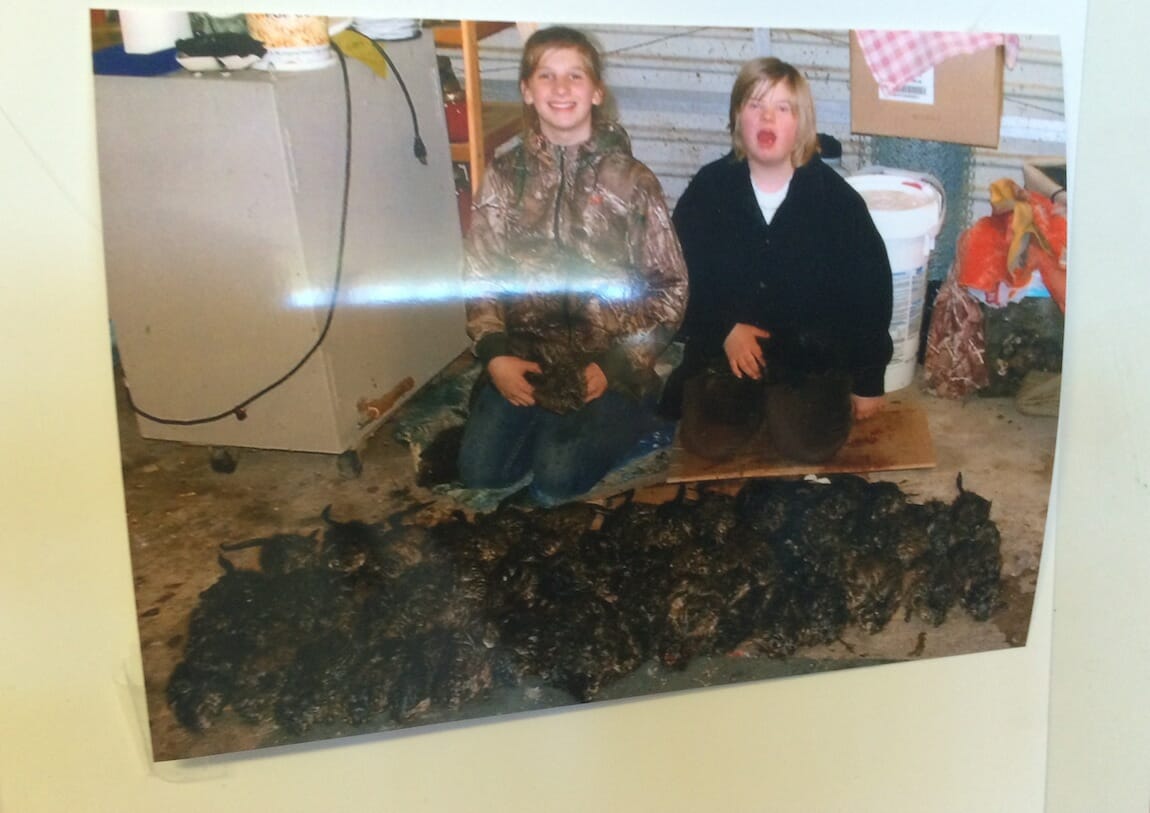

Posing in front of a muskrat bounty.

Getting off the shuttle, furious squawks of trumpeting Canada geese pierce the air. But there are no geese in sight. What I was actually hearing were the throngs of local men and boys who, from inside the school building, were practicing their repertoire of calls for the goose-calling competition. In fact, the entire day would turn out to be punctuated with the sound of the two-part honks ricocheting through every hall and classroom in the building. After paying a six-dollar entry fee and receiving a stamp on our hands (the image of a muskrat), my brother and I went to register my dishes for the cooking competition. We also noticed then that nary a single bar of cell phone reception would be available that day.

The hallways and classrooms of the school were transformed into a makeshift convention center. Artists peddled their wares from folding tables, and taxidermists flaunted fox, pheasants and wood ducks, presided over by the peering heads of antlered whitetail and sika deer. Families meandered through the displays sporting coordinated camouflage ensembles; the Mossy Oak pattern on mom’s vest matching the Mossy Oak camouflage of dad’s baseball hat, their children bedecked in khaki and camouflage dungarees. This was, after all, the National Outdoor Show, I reminded myself, and I started to doubt my own choice in clothing for the day, feeling a bit like I was wearing Duke Blue to a Carolina home game.

y brother and I approached the hand-written sign reading “Muskrat Cooking Competition.” The portion reserved for the contest was part of a classroom that had a laminate counter with a metal sink, a vintage microwave oven, and a white electric range that was clearly sourced just for the competition. There were two lined sheets of paper at the registration point. One read “Traditional,” and the other read “Specialty” at the top margin. “Traditional” is apparently a loose designation for those muskrat dishes that are braised or stewed in very simple preparations. All of the “traditional” entries were in crockpots. The “Specialty” designation is even looser, and permits nearly anything featuring muskrat.

Looking around the room, my brother and I stuck out like two large Asian sore thumbs. Growing up in the South, this self-consciousness didn’t faze us, but we didn’t know if we could expect that that tinge of hostility we are accustomed to in North Carolina – and we wrongly expected the worst. A few older, smiling ladies welcomed us, gently showing us where to reheat my dishes and where to set my plates in time for the judging that would begin promptly at 4:15 pm. They seemed as unconcerned with our foreignness as they were concerned that we would not know how to warm up our plates by ourselves, and they sweetly offered to help do things like set the oven temperature. My brother and I exchanged several well-I-guess-they-actually-don’t-hate-us glances; we quickly realized our Southern experiences had made us more paranoid than we ever knew. The Bacon ‘Rat and the Swampanadas were still concealed under aluminum foil covers and they remained hidden for the next forty-five minutes they spent in the oven.

I could tell, however, that the smiling ladies had only one thing on their mind. Somebody has come to challenge Rhonda Aaron, the queen of Dorchester County.

Rhonda Aaron is a legend. She has been featured in a documentary film and on television not only for her multi-year sweeps of the muskrat cooking competition but also for her reign as one of the top women’s muskrat skinning champions in the history of Dorchester County. As a point of reference, this woman can skin three muskrats in one minute and twenty-four seconds. Rhonda Aaron is also a vision to behold. Her curly red hair stays locked in a clip, her freckled hands work like weapons. As shown on television, she is fit, intense and ageless. By 3:45 pm, there was no sign of Ms. Aaron. I wondered if she had decided to let someone else win in 2014.

While my dishes reheated, I explored the other corridors of the school. When I returned, I spotted Rhonda Aaron registering her dishes from a distance, and then, before I could reach her, she vanished into the thicket of camouflage and blaring geese. By the time I made it back to the preparation tables, I saw her name scrawled on the Specialty ledger below mine. She had dropped off her two entries: a muskrat pot pie and barbecued muskrat. Sitting in the center of her pot pie’s pastry lattice, Ms. Aaron had placed a muskrat-shaped pastry cut-out in the center. The queen is no slouch.

Fifteen minutes before judging began, I reheated the ‘Skurry Curry and ladled it into a green winter squash (the serving bowl) and encircled the squash with tennis ball-sized globes of steamed white rice. I plated the Swampanadas next, arranging them on a long dish garnished with half-moon slices of lime and a spatter of garlic-lime yogurt on the side. Finally, I unveiled the Bacon ‘Rat.

The response was immediate and gratifying. Someone may have squealed. A small crowd started to form around my three dishes, and people started whipping out their cell phone cameras. I started to awkwardly take questions like whether I owned a restaurant and where I learned to cook. They were tickled that people from Washington, D.C., or what they refer to as the “Western Shore” had come so far to participate in their muskrat cooking tradition. At least I was scoring a few points for popularity, I told myself, wandering away during the actual judging, which took place behind portable walls. Half an hour after unveiling the dishes, the cooks and onlookers gathered at the judging table for the announcement of 2014’s muskrat cooking competition winners.

[mf_mosaic_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/IMG_6776.jpg” caption=”In all its glory, the Bacon ‘Rat.”]

First place in the “specialty” category, the first place trophy and $50 in prize money went to Rhonda Aaron’s muskrat pot pie. My faithful friends from D.C. sighed and gave me comforting looks. But then the judges announced that I won not only second place for the ‘Skurry Curry but also third place for the Bacon ‘Rat, netting me a large trophy and $35 in prize money. (The 2014 Second Place Muskrat Cooking Competition trophy, by the way, is nearly two feet tall and features a gilded print of a muskrat in a chef’s hat holding a wooden spoon. This follows me to my grave.)

I would be lying if I said, after weeks of preparation, placing in the competition wasn’t a relief. I would also be lying if I failed to mention that the total number of entries in the “specialty” category was five ”“ my three and Rhonda Aaron’s two. I had to at least place third. But apart from the relief, I felt humbled because these people from Dorchester County gave me a fair shake, and their graciousness and warm hospitality into their muskrat culture nearly brought me to tears. They clapped for me. They smiled warmly at me and patted me on my back when I walked up to accept my trophy even though Rhonda Aaron was conspicuously absent.

In the moments following my win, I basked in the glow of an old trope: I was Kevin Costner in “Dancing with Wolves;” I was John Smith in “Pocohontas;” I was finally Ralph Macchio in “Karate Kid Part II.” My second place trophy was the magical talisman I received from the chief of the tribe, and if it weren’t so inconvenient for me to hang it from a leather cord around my neck, I would do it. I was already thinking about next year’s contest and how the stage was set for next year’s showdown between Ms. Aaron and me. And then I sobered up.

Since the contest’s end, I have not eaten muskrat. The muskrat’s flavor, like many flavors that we acquire through culture and convention, is really not for everyone. Friends and relatives have shuddered as I recounted my tribulations leading up to the contest, and I have had to justify eating this organic, free-range animal in ways I did not anticipate.

Consuming muskrat, it turns out, is just as polarizing as the partisan divides that consume Washington. But if history teaches us anything, it’s that approval ratings are a fickle mistress. The muskrat couldn’t fit in better in this town.

‘Skurry Curry

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

2 tablespoons Thai red curry paste

2 14-ounce cans coconut milk

1 cup chicken stock

2 tablespoons brown sugar

2 tablespoons fish sauce

½ red onion, chopped

½ cup chopped cauliflower florets

½ cup sliced carrots

½ cup chopped red bell pepper

½ cup canned pineapple chunks, drained

1 cup Maryland muskrat, previously boiled and chopped

4 cups steamed white rice

1 tablespoon salt

[Optional: 2 Lime leaves; 1 knob sliced Galangal; 1 stalk Lemongrass, chopped ]

1. Add 1 tablespoon vegetable oil to medium-sized, heavy bottom pot. Sauté onion, cauliflower, carrots and red bell pepper for 3 minutes, stirring frequently. Remove from heat and set aside.

2. Add additional tablespoon vegetable oil to same pot, add curry paste and fry for 30 seconds. If using galangal and/or lemongrass, fry here too.

3. Add coconut milk, chicken stock, fish sauce, brown sugar and lime leaves (if using). Stir to incorporate.

4. Bring curry to a boil, and then reduce to simmer.

5. Dissolve salt into warm bowl of water. Wet hands (to prevent sticking) and form balls of rice the size of tennis balls.

6. After simmering curry for 15 minutes, plate the rice balls and ladle curry over them. Optional: serve curry from a hollowed out pumpkin.

Swampanadas!

Garlic and Lime Yogurt Dressing

4 tablespoons plain yogurt

Zest and juice of one lime

2 cloves garlic, finely minced

1/8 teaspoon salt

1/8 teaspoon pepper

Combine all ingredients into a bowl, stir to incorporate, cover and set aside to cool in refrigerator.

Swampanadas

1 yellow onion, finely diced

4 cloves garlic, finely chopped

1 cup green olives, chopped

1 red potato, diced

1 14-ounce can diced tomatoes, drained

3 hard-boiled eggs, chopped

1 teaspoon ground cumin

½ teaspoon Old Bay seasoning

½ teaspoon ground oregano

¼ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon pepper

¼ teaspoon cinnamon

1 ½ cups Maryland muskrat, previously boiled and chopped

1 tablespoon distilled vinegar

2 packages puff pastry dough

1 egg

1. Over medium-low heat, sweat onion and garlic until translucent. Season with salt and pepper.

2. Add chopped olives, diced tomatoes, diced potatoes and vinegar. Stir to combine.

3. Add cumin, Old Bay, oregano and cinnamon. Simmer until liquid boils off.

4. Add muskrat and cook for two minutes.

5. Remove from heat and fold in chopped hard-boiled eggs, and set aside to cool.

6. Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

7. Flour surface of counter and roll out puff pastry to ¼-inch thickness.

8. Cut puff pastry into six-inch disks (you can use upturned soup bowl for guidance).

9. Add two tablespoons of Muskrat filling into center of each disk.

10. Wet fingers with water and rub around perimeter of disk.

11. Fold disk in half, and pleat to close.

12. Brush dough with beaten egg and place on a baking pan lined with aluminum foil and spray of Pam to prevent sticking. Bake for 45 minutes.

13. Serve with Garlic Lime Yogurt.

Maple Bacon ‘Rat

Maple Bourbon Glaze

2 tablespoons ketchup

2 tablespoons brown sugar

½ cup orange juice

½ cup maple syrup

2 tablespoons soy sauce

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon pepper

Add all ingredients to saucepan, simmer until reduced by one-half, set aside.

Bacon ‘Rat

12 slices bacon

1 14-ounce package smoked sausage or kielbasa

2 cups white mushrooms, sliced

2 bunches green onions, finely chopped

6 Italian sausages, removed from casings

1 ½ cups Maryland muskrat, previously boiled and chopped

2 tablespoons hoisin sauce

1 cup heavy cream

2 tablespoons Old Bay seasoning

Assorted fresh herbs for garnish

1. Preheat oven to 225 degrees.

2. Stir hoisin sauce into muskrat. Set aside.

3. Weave bacon lattice (6 slices x 6 slices) and then dust generously with Old Bay.

4. Chop remaining bacon slices and fry in a sauté pan, then cook mushroom slices in bacon fat, seasoning with dash of salt and pepper. Set aside.

5. Press/spread layer of Italian sausages evenly over bacon lattice.

6. Press/spread layer of chopped bacon and mushrooms evenly over Italian sausages.

7. Press/spread layer of green onion evenly over chopped bacon and mushrooms.

8. Spread layer of muskrat evenly over green onions.

9. Slice one smoked sausage in half lengthwise, and lay the halves diagonally across the bacon square, the second half hanging over the edge to form tail. (Carve/twist second half for optimal tail-like aesthetics.)

10. Hold corner of bacon lattice, and roll the entire mat tightly. Fold over corner for face of muskrat.

11. Place in baking dish and bake for 2 hours, basting periodically with maple bourbon glaze.

12. After removing from oven, stir heavy cream into the remaining bourbon glaze, and pour into the bottom of the baking dish. Garnish with assorted fresh herbs.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Troy Andrews, Modern Farmer

March 26, 2014

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

After reading an article that said the Catholic church approves eating muskrat in Lent, I looked up muskrat recipes and found your beautifully written article. I had fun reading it to the family. My North Dakota in-laws trap muskrat and beaver. I always wondered why we didn’t eat it. It seemed a shame to just feed the carcasses to cats. Now I know.

Sorry but I’ll have to pass on the whole “eating rodents” thing unless I’m starving to death. Cool post anyway, I never realized there was such a large interest in muskrat cooking specifically.

From a fellow Cantonese North Carolinian who likes to learn obscure, primarily culinary, things: thanks for such a fun read! I did not expect this level of entertainment when I clicked this link buried in my latest Atlas/Gastro Obscura article.

Do you sale the muskrat when you clean them

Do you sale the whole muskrat meat

This was an awesome read. Guess I won’t try cooking up rats* for now. But if I do I’ll give either your 2nd or 3rd place recipe a try…. but probably not lol. Thanks for the entertainment.

Does it taste like elephant ?

the simple solution to this entire issue is to incorporate spam into the recipes. I am surprised you didn’t think of it.

Very fun read! Thank You.

Where can I obtain muskrat meat without having to trap them?