Old Time Farm Crime: The Werewolf Farmer of Bedburg

It wasn’t easy being a farmer in 16th-century Germany. It was even harder when you were accused of being a werewolf who had made a pact with the Devil.

Old Time Farm Crime: The Werewolf Farmer of Bedburg

It wasn’t easy being a farmer in 16th-century Germany. It was even harder when you were accused of being a werewolf who had made a pact with the Devil.

It was hard enough just to get anything to grow in a time before pest control and fertilizers. Then there was the constant threat of roving brigands who had no qualms about stealing your livestock or burning your crops. But for farmer Peter Stubbe, life was even tougher. Stubbe also had to deal with accusations of being a werewolf in cahoots with the Devil who murdered children and pregnant women.

Stubbe (or Stuppe, Stumpp, or Stumpf depending on the source) was a prosperous farmer who lived just outside Bedburg, a small city in Germany’s Rhineland, then part of the rickety Holy Roman Empire. It was a time of upheaval, with Protestants fighting Catholics and a whole lot of power struggles by various minor princes and other such royal riff-raff. The area where Stubbe lived had most recently been devastated due to the Cologne War, also known as the Sewer War (the name is apparently derived from a battle in which Catholic forces stormed a castle through its primitive sewer system).

It was at this time that townspeople began turning up dead. There were whisperings of a wolf-like creature roaming the countryside killing both humans and livestock. The creature was described as “greedy… strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like unto brands of fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharp and cruel teeth, a huge body and mighty paws.”

The creature was described as “greedy… strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like unto brands of fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharp and cruel teeth, a huge body and mighty paws.”

People were soon traveling from town to town only in large, heavily armed bands. Travelers would sometimes stumble on victims’ remains in the fields, raising the level of terror even higher. When a child would go missing, the parents would immediately assume all was lost and that the wolf had taken another victim. Although every effort was made to try and kill the creature, it eluded capture for several years until 1589 when a group of men tracking the wolf with their hounds encircled it.

When they moved in for the kill, the wolf was nowhere to be seen. They instead found Stubbe. There seems to be some confusion as to whether they actually saw him transform back from being a wolf or if he just happened to be traveling through the woods at this inopportune moment. Either way, under the threat of torture he confessed to the murders of 13 children, two pregnant women and one man. But that was just the start of it.

According to an anonymous pamphlet that circulated in London the next year that was based on an earlier Dutch version and is the primary existing source of Stubbe’s tale, he told his captors that at age 12 he made a pact with the Devil, with the Prince of Lies getting his soul in exchange for numerous worldly pleasures. But this wasn’t enough to satisfy Stubbe, who was “a wicked fiend pleased with the desire of wrong and destruction” and “inclined to blood and cruelty.” So the Devil gave him a magic belt that turned the farmer into a killing machine in the form of a wolf.

Thusly attired, Stubbe went on a spree taking “pleasure in the shedding of blood,” eating unborn children, as well as killing and eating his own son borne out of an incestuous relationship with his daughter. He allegedly took a she-demon as a mistress, along with a good Christian woman he seduced, and generally committed murder and mayhem on a grand scale. He also apparently had a penchant for livestock – one would guess that as a prosperous farmer he wasn’t killing his own animals – and especially liked lambs and kids (baby goats, in this case, as opposed to human children).

Stubbe, who loved his secret life as a werewolf, took great pleasure in walking through the streets of Bedburg, hailing the families and friends of his victims, none of them aware that the gentleman farmer was a homicidal maniac. During these sojourns he would sometimes pick out his next victim and by whatever means he could, would get them out into the fields where he would “ravish them… and cruelly murder them,” according to the pamphlet.

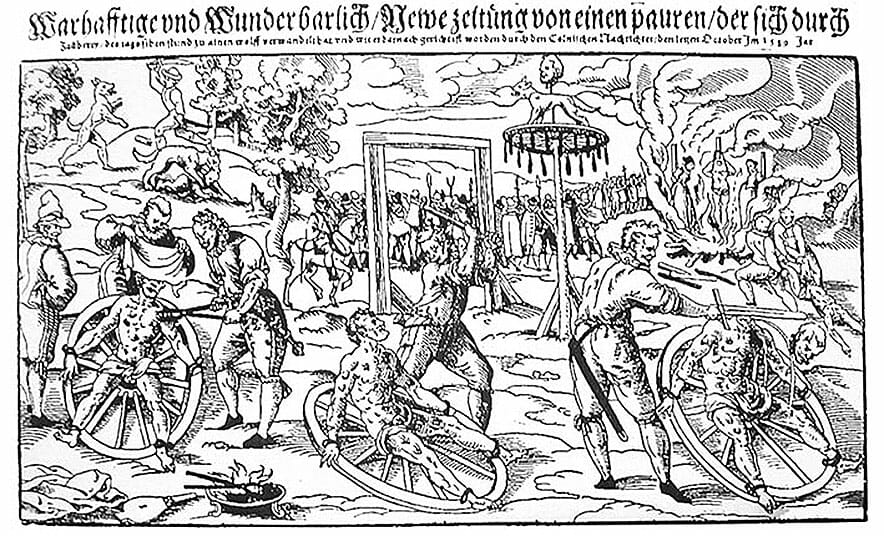

For Stubbe’s alleged crimes he was ordered to “have his body laid on a wheel, and with red hot burning pincers in ten several places to have the flesh pulled off from the bones, after that, his legs and arms to be broken with a wooden ax or hatchet, afterward to have his head struck from his body, then to have his carcass burned to ashes.” His unfortunate daughter, Beel Stubbe, and his mistress, Katherine Trompin, were also put to the stake as accessories to the murders.

Geography, religion and politics worked against Stubbe. He was living in an era of werewolf hysteria in both Germany and France that reached its zenith in the 1590s. In times of chaos, people have traditionally blamed things on the supernatural and usually looked for the oddest, and least well-connected, person in town to use as a scapegoat. In Stubbe’s case, it’s likely that his being a Protestant in an area that was at the time being held by Catholic forces that may have made him a target.

The Sewer War, which lasted from 1583 to 1588, began as a small-time conflict in Cologne over whether the prince-elector of the city who had just converted to Protestantism could force the conversion of his subjects. Soon Spanish troops and Italian mercenaries were brought in on the side of the Catholics, while monetary support from France and England poured in for the Protestants.

This war was a warm-up for the much bigger, and longer, 30 Years War, which as the name suggests lasted for three decades (1618 to 1648) and was both a religious and a politically motivated conflagration involving several European countries that began as a fight between Catholics and Protestants within the Holy Roman Empire and evolved (or devolved, depending on your perspective) into a power struggle between the house of Bourbon in France and the Hapsburgs of Austria.

With that in mind, it’s worth exploring whether Stubbe was actually a serial killer who believed himself to be a werewolf. For thousands of years, straight back to the epic poem of Gilgamesh, humans have believed in lycanthropy, a fancy term for the act of becoming a werewolf. In the 1500s, there was a rash of trials for people accused of being werewolves, with most of the proceedings ending in the accused being put to death. But even at that time, among the educated, the idea of lycanthropy was beginning to be understood as psychologically based. Five years before Stubbe was put to death, the writer Reginald Scot, in his book “Discoverie of Witchcraft,” argued “lycanthropia is a disease, and not a transformation.”

In Stubbe’s case, it’s possible he was suffering from clinical lycanthropy. The diagnosis (recognized in the DSM-IV) is thought to be a cultural manifestation of schizophrenia, and associated with bouts of psychosis, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and “grossly disorganized behavior.” There was a documented case from the 1970s, in which a 49-year-old woman, after having sex with her husband “suffered a 2-hour episode, during which time she growled, scratched, and gnawed at the bed,” according to Harvey Rostenstock, M.D. and Kenneth R. Vincent, Ed.D. in their article in The American Journal of Psychiatry. The woman later said the Devil came into her body and she became an animal. The article goes on to say that “there was no drug involvement or alcoholic intoxication.” This was just one of the instances in which the woman had a lycanthropic episode. The authors opined that people experience lycanthropy when their “internal fears exceed their coping mechanisms” and they externalize those fears “via projection” and can “constitute a serious threat to others.”

And it’s not just wolves that sufferers of clinical lycanthropy “transform” into. While in many cases lycanthropy is associated with wolves, there have been cases where patients believed they were sharks, leopards, elephants or eagles, among other “feared” animals.

In pre-20th-century Europe it made sense that the wolf was the “feared animal” of choice for someone suffering from lycanthropy, since wolves could wipe out a farmer’s livestock (and thus their livelihood) fairly easily and were known to kill humans, mostly children. For example, in a three-month period in Central Sweden, between December 1820 and March 1821, there were 31 wolf attacks resulting in 12 deaths. All the fatalities except one were children and it was believed a single wolf killed them.

The truth behind Stubbe’s story, like countless others who suffered similar fates, remains lost to history.”Throughout the ages, such individuals have been feared because of their tendencies to commit bestial acts and were themselves hunted and killed by the populace. Many of these people were paranoid schizophrenics,” write Rostenstock and Vincent.

Following Stubbe’s execution, the wheel on which the farmer suffered unspeakable pain was attached to a high pole and left on public display in Bedburg as a “continual monument to all ensuing ages,” an image of a wolf and a likeness of the farmer secured above.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Andrew Amelinckx, Modern Farmer

August 5, 2013

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.