Poor Dr. C. J. Sketchley. If it wasn't the tourists trampling his crops or dogs scaring his ostriches, it was thieves attempting to pluck the birds for their valuable plumage.

Poor Dr. C. J. Sketchley. If it wasn’t the tourists trampling his crops or dogs scaring his ostriches, it was thieves attempting to pluck the birds for their valuable plumage. It was 1883; Sketchley’s ostrich farm in Anaheim, Calif. was just getting off the ground and was quickly becoming a tourist destination, much to the farmer’s chagrin.

“When you ask me what are the greatest drawbacks I have met with I must answer dogs and visitors, and perhaps the visitors are worst,” he told a reporter for the San Francisco Bulletin.

Sketchley had previously run a similar operation in South Africa before the First Boer War dispersed his flocks and drove him to America. His farm in the States was well thought out – everything organized like a smooth-running machine – but he never expected the crowds.

Hundreds of people a day appeared unannounced and uninvited to get a look at the exotic animals and apparently had no qualms about breaking the lock on the incubator room to stare at the large eggs as they waited to hatch, jumping fences to get a better view of the operation and even entering the doctor’s house to rummage through his papers. But the worst were the pluckers.

At one point, the doctor had to run off a well-dressed gentleman who he caught in the act of denuding one of the birds. He barred the would-be thief forever from the farm under penalty of arrest.

At the time, a pound of top quality ostrich feathers went for $400 (about $9,400 today). A pound of gold was worth only $332.

Sketchley even tried charging the equivalent of $12 a head for admission to try and discourage the riff-raff and yet the problems persisted. All he wanted was to be left alone to build his business. Sketchley believed the sale of the feathers would become a booming industry as profitable as gold or silver mining was in California. It wasn’t just a pipe dream. According to an 1882 New York Times report, a pound of top quality ostrich feathers was going for as much a $400 (about $9,400 today). The price of an equivalent amount of gold was about $332.

What drove this ostrich feather frenzy was fashion. As far back as Classical Greek and Roman times warriors prized the feathers, which they used to decorate their helmets. From Egyptian pharaohs to the later royalty of Europe the feathers were sought after to the point where wild ostrich herds were devastated and commercial ostrich farming began to pop up. By the late 19th century the industry was established in South Africa thanks in part to wire fencing, mechanical egg incubation and the cultivation of alfalfa, the bird’s main food source.

Sketchley calculated one bird produced about $250 (about $6,000 today) worth of feathers a year, and best of all, the product grew back. The plucking process was dangerous for the plucker – an ostrich can disembowel you with one well-placed kick – and painful for the pluckee. But the rewards were apparently worth the risk to both legitimate farmers and criminals.

In South Africa, there was so much ostrich feather theft that the Cape of Good Hope’s parliament passed specific laws dealing with the crime in 1883, with revisions in the following years. In 1907, with the crime still raging across the country, the parliament again sat down to hash out a new law to deal with the issue and – in boring bureaucratic fashion – titled it the Ostrich Feather Theft Suppression Bill.

The bill dealt with such issues as the issuance of licenses for ostrich feather dealers and brokers (and barring anyone who was previously busted for the crime), registering ostrich farmers and allowing police to regularly check the books of feather dealers.

Ostrich farming was big business for the South African colony. In 1905 alone more than 471,000 pounds of feathers worth more about $24 million in today’s dollars were exported. In 1913, ostrich plumes were South Africa’s biggest export behind gold, diamonds, and wool.

The last great fashion craze that supported the industry was Victorian and Edwardian women’s hats, and in to a lesser extent, handheld fans. The trend in feathered headgear blew up in the late 19th century and lasted until the eve of World War I. It saw not just the rise of ostrich farming, but the devastation of wild bird species, since the rarer the bird on one’s hat, the higher the wearer’s social standing.

In 1886, the American Ornithologist Union estimated that five million North American birds were killed each year for the millinery business. That year, bird enthusiast Frank Chapman, who worked in Manhattan, recorded seeing, in a two-day period, 174 birds – 40 species in all – on women’s hats as he walked through the city’s streets.

With any money making enterprise comes the underbelly of criminal activity leaching off of it. Across the globe, going back to at least to the 1700s, there were myriad cases of the theft of ostrich feathers, but most involved the already plucked variety. In 1788, Mary Adams was convicted in London for stealing a single ostrich feather (along with clothing and a thimble) and was sent to Australia, then a burgeoning penal colony, for a seven-year stint. She died there the next year. In New York in 1874, an enterprising 16-year-old named John Hughes who worked for a feather dealer was busted after stealing about $12,000 in today’s money worth of ostrich feathers.

In response to the craze for bird feathers, the Audubon Society and other conservation organizations shamed women into foregoing their bird covered fashions. Fashions changed and the ostrich feather industry declined.

Dr. C. J. Sketchley eventually gave in to the crowds: He moved his farm just outside Los Angeles, partnered with another entrepreneur with the unlikely name of Col. Griffith Griffith, and put in a rail line that went from the city to the farm, now a tourist attraction that would one day become L.A.’s Griffith Park. Besides the working ostrich farm, there were other exotic birds on display, along with promenades, a bar and a dance floor. With time, Sketchley moved the farm once more before going bust.

Today, the industry continues to live on with the feathers still finding their way into fashion, just not on the same scale as in the past. And yes, 130 years after the good Doctor Sketchley was dealing with the illegal plucking of his birds, the crime continues as well.

In April, five people were arrested in Oudtshoorn, South Africa, for stripping feathers from live ostriches that mostly came from a government research center. About 70 birds were plucked and four were bludgeoned to death, according to various reports.

Andre Prinsloo, 21, Jakobus November, 28, Karel Jansen, 35, Jonas Jansen, 25, and Dawid Piedt, 31, are charged in connection with five cases of alleged theft of ostrich feathers, worth about $12,000 U.S. Their cases remain pending.

“The ostrich industry has suffered substantial damage due to the stripping of ostrich feathers and we therefore hope the arrests are a deterrent to potential poachers,” Western Cape Police Captain Malcolm Pojie told reporters.

Like the proverbial ostrich sticking its head in the ground, these enterprising (alleged) criminals failed to learn from those who came before and ended up behind bars – or in the case of Mary Adams, dying in a penal colony thousands of miles from home – all for stealing from our fine feathered friends.

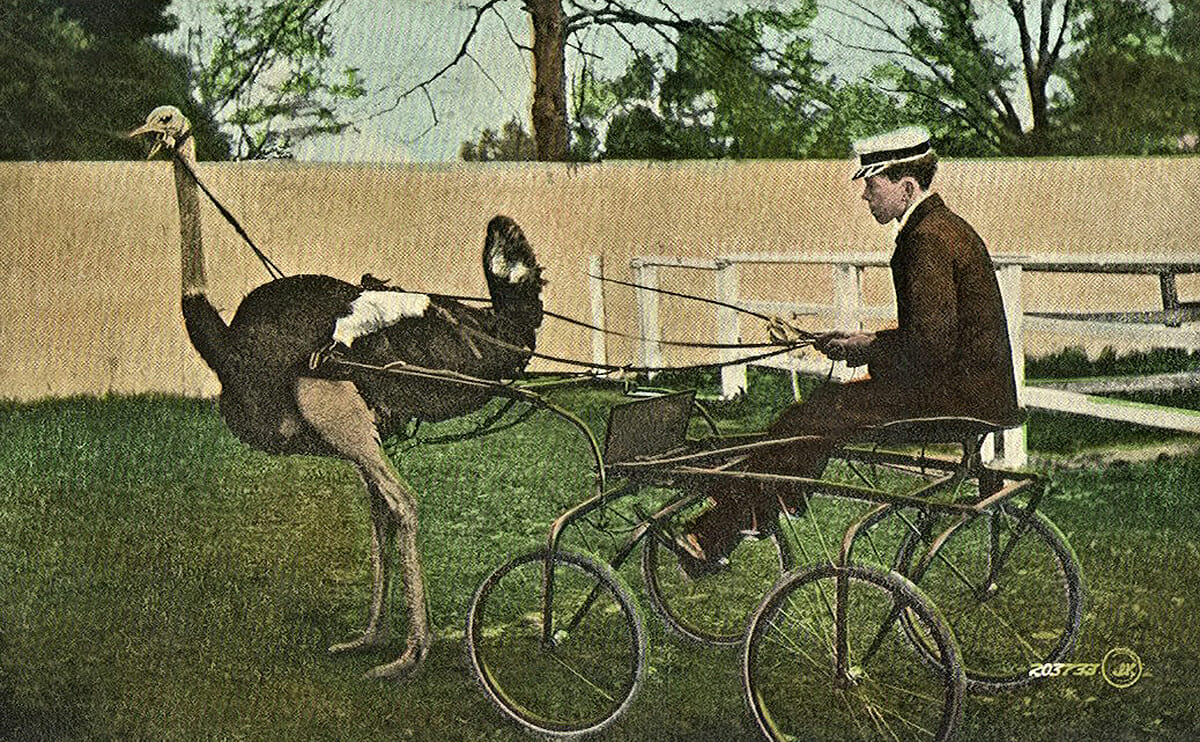

(Image credit: A postcard published by the Valentine & Sons’ Publish Company, New York and Boston, mailed and postmarked 1911/Wikimedia Commons)