We talk to Forrest Pritchard about farming, his book Gaining Ground, and how the agricultural landscape in the United States has changed since he started out in the mid-1990s.

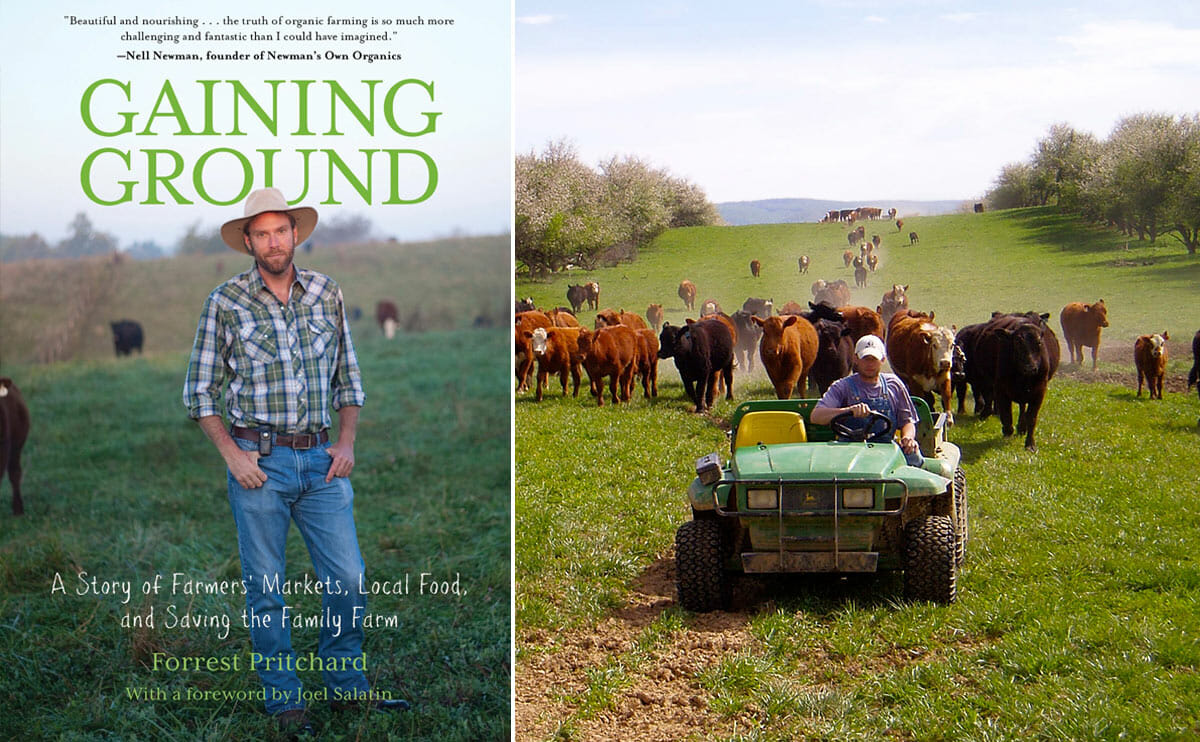

In addition to operating Smith Meadows Farm (above) — one of the first “grass-finished” farms in the country — Forrest Pritchard is the author Gaining Ground, an account of his turbulent, but ultimately successful journey as a farmer in the Shenandoah Valley, and a book that has met with overwhelming success since it was published in May. Last week, Forrest was kind enough to speak with Modern Farmer about farming, Gaining Ground and how the agricultural landscape in the United States has changed since he started out in the mid-1990s.

Modern Farmer: In the introduction to Gaining Ground, Joel Salatin implies that you have a certain X factor that has sustained your farming passion while many others, he suggests, become more discouraged along the way. What do you think that X factor is?

Forrest Pritchard: I’ve never really thought about that, but if I had to put my finger on it, I’d say that it is a faith-based motivation that a lot of multi-generational farmers share. That is to say, something that’s bigger than money or anything like that. I think there’s probably a bit of a difference between a first-generation person who is very interested in wanting to farm maybe for philosophical reasons, or maybe because they think it’s a sound business decision and farmers who have been born into the land and have been surrounded by fields and forests and streams and all these things. You have a real sense of stewardship that becomes a multi-generational perspective if it’s not about one farmer. It’s about the generation before and the generation that comes afterwards. If I had to determine an X factor, that might be it.

MF: You offer a farm apprenticeship program now, but you didn’t go through one yourself. Is that something you thought about doing when you started out?

FP: When I started out in 1996, I’m honestly not sure how many farm apprenticeships there were out there. There might have been some, but one thing for young people especially to keep in mind is that the Internet was nothing back then. It’s now this hugely powerful leveraging tool that we can use for resources like researching farm apprenticeships, blogs or pertinent books. Back then, the internet basically didn’t even exist, so even if I had wanted to research apprenticeships, I don’t even know how I would have gone about it. One used to go the library and look up stuff in the encyclopedia. I assure you there are no listings for apprenticeships in the Encyclopedia Britannica.

My grandfather had done it, and even though my parents had had off-farm jobs, they had managed to hang onto it somehow, so I just figured if I went at it full-time, it would somehow sort itself out and eventually it did. But that’s nothing that an apprenticeship wouldn’t have helped along the way. But frankly in ’96 ”“ ’97, the world wasn’t as ready for direct marketed organic local foods as I thought it was.

MF: In the book, several decisions you make ”“ especially at the beginning ”“ appear to come from the gut. But farming is also undeniably about precision. How much of what you do is intuitive and how much of it is mathematically precise?

FP: I think farming is a wonderful intersection of art and science. There’s so much that we can learn from an agricultural degree or self-education, and then there’s this point of departure where you have to have a relationship with the land that you live on. As a livestock farmer, as a pasture farmer, I have to know what my farm’s carrying capacity is. And as much as I want to send off soil samples to Penn State or Virginia Tech, those scientific results of organic matter and nitrogen and phosphorus content aren’t necessarily going to intersect with my farm’s ability to absorb rainfall. There are so many instances where you have to not only know the land but you also have to have a familiarity with the seasonality of it. That doesn’t come in just one year; that comes in multiple years. It’s a constantly evolving process.

Intuition has to play a role because the land is constantly trying to communicate with us as stewards, like “Look, we’ve got too much pressure over here, we need more fertility over here. This has been neglected, etc.” And in a lot of ways farmers’ markets are like that too. Frankly, not to make too big of a jump, customer relationships and marketing are a lot like that too. It’s a constant communication of where more effort needs to be, where you’re doing ok, and where things just probably aren’t going to work out.

MF: At a certain point, you decided to sell the majority of your farm equipment. What are the essentials that a farmer like you can’t do without?

FP: Gordon Hazard always says he has a pickup truck and two hammers. And you could probably get it down to a four-wheeler. There are plenty of farmers who operate on a four-wheeler and some hand tools. That’s not to say, though, that they’re direct marketers. I mean, there’s nothing like having a refrigerated box truck and some freezers and stuff like that to make everything go. I’m a firm believer that to be fully sustainable, the animals have to do as much as possible. So if we can constantly try to re-imagine what we could be doing with the animals instead of relying on machinery, then that’s the mindset where things need to be.

To put that into perspective: this time of year in the Shenandoah Valley, everybody is either making hay or bush hogging ”“ mowing ”“ and why do we do that? I understand that there’s some hay that has to be made, but for the bush hogging, I’ve never understood it, and it’s something that I did forever and ever. Several times a year, I’d just go out and mow my pastures. I ask farmers why they do that and they say that it’s for visibility ”“ to make the farm look tidy ”“ and to control brush, but if we can trade our time, tractors, diesel fuel, wear and tear… storage, all these input costs on machines that we have to upkeep, and trade that for animals that do the same job — that doesn’t require a huge leap of faith. That just requires a different way of thinking about how management works. Once you get into it, it becomes a really sensible and sustainable solution, and you’re just refining your management techniques.

That being said, there’s nothing like a four-wheel-drive tractor. A four-wheel-drive tractor with a front load is a pretty sweet thing to have. But then again, you can always rent one. Within a hundred-mile radius, or fifty miles even, there’s going to be someone in a town that will rent you a four-wheel drive loader for a day and a half if you really need one. New farmers, especially, don’t have to pigeon-hole themselves into thinking they need all this stuff.

MF: You post musings fairly frequently on your farm’s blog, but it seems as though you also dedicate quite a bit of time responding to comments. Why is that?

FP: I’m in the customer relationship business. My business absolutely relies on customers choosing to buy my products. Why is it that people opt for a small farm instead of going to their Whole Foods or going to their Trader Joe’s or paying online or just dismissing it all and shopping at a Food Lion or Safeway or Costco? It all comes down to choosing to shop at that farm for whatever reason, and for every customer that I’ve got, that shops with me at a farmers’ market or at my farm, they shop with me for a different reason. But it is a reason that is unique to my farm, whether it’s the issue of humane treatment of animals or humane slaughter methods or lack of antibiotics or a commitment to environmental sustainability. Whatever the reason is, they choose to shop with me and if I’m going to be anonymous and raise anonymous food, and not put myself out there at farmers’ markets, not respond to comments, not have any kind of personality, then I might as well be like a wholesaling commodity farm. I might as well just be sticking it in a supermarket somewhere and let someone rebrand it as grass-fed beef, and hope that I’m making a difference. Responding to comments, it feels like the least I can do. If somebody wants to reach out to me and spend five minutes writing a comment, I can take the time and write back to them.

MF: About a third of the way through the book, you write, “In my more idealistic moments, I imagined a small army of farmers like myself, a loosely connected tribe, each producing what we could reliably grow and each selling directly to our surrounding.” In 2013, is that still idealistic or is it realistic by now?

That’s a difficult question to answer. I’m a bit myopic insomuch that I’ve got my own farm to deal with. I’m not the meat king of Berryville, Virginia, much less Washington D.C., much less the world. And I say that jokingly, but a small family farm is just intended to serve its local community. That’s the way they’ve always been, historically.

But that’s where the book was intended to come in — to say, you’re not alone. All these problems that someone in Missouri on their family farm might be having, or in Idaho, or wherever, you’re not alone. You’ve got allies out there.

On one side, it’s intended for people who are producers, but let’s face it, around one percent of people are even involved in farming, much less the actual producers. Far less than one percent are the actual farmers. So this book isn’t really going to be useful just for producers. It has to be useful to the other 99 percent, who are the consumers. So if it’s going to be useful from a consumer’s standpoint, the consumers need to be able to say, “Look, this food is authentic. It does have an identity. It does have a soul. It’s got a face behind the production.” And the choices that they make are really impactful for whether a farm is going to continue for another generation, or even for another year, for that matter.

So if the message could be, there is this spirit that customers can vote for, tangibly vote for with their dollars and make a real contribution to, that they can be vicarious participants in this tribe of people that are trying to make a difference, then that’s a really empowering thing, and that’s what the book tries to get across.