Corn tortillas are an integral part of the Mexican diet. But the native corn species, and the traditional way of making them, are disappearing. A new company called Tamoa is trying to change that.

There is nothing more integral to Mexican cuisine than corn and tortillas, but both native corn species and quality tortillas are in grave danger of disappearing in this country where they have been cultivating ‘maiz’ for at least 8,000 years. The problem is especially serious in the cities where access to good tortillas is a huge issue, with most relying on store-bought tortillas or cheap tortilleria shops that use Maseca, a type of instant corn flour that often is made with imported American corn.

There is a movement to ‘save’ the tortilla by focussing on tradition and quality, but it is still quite an elite product, mostly found at expensive restaurants. The young couple Francisco Musi and Sofia Casarin are working to make good tortillas more accessible with their company Tamoa. Based in Mexico City, they are establishing relationships and networks with farmers in nearby states to help keep the transportation costs low. Paying a fair price directly to corn producers is a core principle of their project so that farmers don’t have to leave their communities to search for other work. They focus on sourcing quality heirloom corn from small-scale farms, making sure to only buy surplus production in order not to deprive farmers and their families of their ancient food rites. They supply a number of Mexico City restaurants with both dried corn and masa dough.

Tamoa actually started with an international focus—in some ways chefs outside of Mexico have been more interested in investigating and recuperating the corn/tortilla tradition than those back home—and they have exported corn and expertise to chefs in the US, the UK and Canada. In a way, their company marries the far-flung interchange of globalization with the ethos of local food to create a sustainable way forward for corn and the tortilla. Since launching Tamoa over a year ago, they have been vigilant in growing smartly so that change is both real and sustainable. They are driven by curiosity and passion for their Mexican heritage and are part of the new generation that is making sure the country’s food cultures are revitalized in the 21st century.

The couple behind Tamoa, Francisco Musi and Sofia Caserin, on a sourcing trip to a small town in the state of Tlaxcala, Mexico.

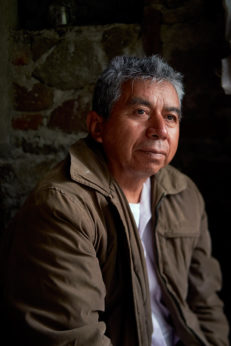

Juan has been a corn farmer all his life; he only grows high quality heirloom varieties. He is very proud of his work, recognizing the value in what he is producing. Farmers in Mexico are among the poorest people in the country and there is very little government support for farmers like Juan. Often producers are forced to sell their corn in bulk for very little money to ‘coyotes,’ middlemen who roam the country and sell to industrial clients—the prices they pay frequently results in farmers actually making a loss on their crop. Tamoa is working to create connections and build networks so farmers can know that they have a reliable buyer who will pay properly for the quality corn they produce.

An ear of an heirloom corn variety called ‘Cónico Morado’. Depending on when it is harvested it can have different uses. Harvested early it is boiled and eaten on the cob as ‘elotes’. The later harvest will be dried, so then it can be processed into ‘masa’, the corn dough that is used to make tortillas, or used to make ‘atole agrio’, a traditional, pre-Hispanic hot drink.

Plots of land in Ixtenco where farmers grow their corn. La Malinche Volcano in the distance.

Cornelio is a corn farmer in Ixtenco, but he is also an organizer, community builder, anthropologist and advocate, who started the local annual corn fiesta. He is passionate about heirloom corn and the farming way of life.

Simon’s family has farmed corn for many generations, and there’s nothing more that he would like than to continue that tradition. However, corn farming isn’t currently sustaining him and his family. Having worked in the US before, and having few other options, he’ll be returning this year to work in construction. He’ll be gone for 3 years, leaving his family to take care of the fields. Buyers like Tamoa can help raise the price of heirloom corn so that farmers like Simon can be paid fairly for their crop and afford to stay in Mexico with their families.

There are some 60 native species of corn in Mexico, but each one has uniquely adapted to its geography through thousands of years of seed selection and saving. The silk of the corn is composed of hundreds of hairs, each one connected to a single kernel, which must be pollinated individually. This is why, when cross-pollination occurs, there is a rich tapestry of colours on a single cob. Once harvested, corn is left to dry completely so it can then be cleaned, stored and ultimately processed into corn-based products.

The old corncobs, or ‘olotes’ are strung together to create a tool for efficiently removing the dried kernels from the ears of corn. This is called an ‘olotera’

Juan cooks fresh tortillas outside on a ‘comal,’ a kind of traditional Mexican griddle. The tortilla is a staple of the diet here and provides a large portion of peoples overall nutrients and energy.

A bag of Tamoa’s corn sits in the kitchen at Los Loosers Restaurant in Mexico City. Tamoa works with the producers to ensure the corn is not only of excellent quality but is also cleaned properly to make it suitable for storage, sale and export.

The nixtamalization process begins at Los Loosers restaurant, by adding water to the dried corn. This is a pink heirloom variety that Tamoa sources called ‘Cónico Rosa’

The corn is boiled with ‘cal’ or calcium hydroxide, commonly known as ‘lime,’ which transforms the corn, making it much healthier and more digestible. Essentially, it makes the nutrients accessible. Because this is more time consuming and labor intensive, many now skip this essential step, particularly when producing on an industrial scale. Corn that has not been nixtamalized is, nutritionally speaking, a vastly inferior product. The prevalence of tortillas not made with the proper ‘nixtamal’ is likely to be in part to blame for the declining health of the Mexican population.

The nixtamalized corn is left to soak with the cooking water and lime overnight. This corn is now called ‘Nixtamal’. In the morning it is rinsed and then it is ready to be milled.

Maria Vicaria Martínez Martínez, a member of the kitchen team at Los Loosers, mills the the nixtamalized corn (the ‘Nixtamal’), passing it through the hand mill at least twice with a little water to obtain the correct consistency for tortilla dough, or ‘masa.’ Tamoa also make their own masa to supply a number of restaurants in Mexico City. Making use of an industrial mill enables them to scale up the process and keep production costs lower to be able to sell the masa at a good price point. Some of the establishments they supply are very casual, everyday eateries, edging them closer to their goal of democratizing properly made tortillas.

The masa is portioned out ready to be pressed. Los Loosers restaurant buys both blue and pink corn from Tamoa.

The masa is pressed by hand using a tortilla press, into a flat disk. There are machines that can automate this part of the process when producing tortillas on a larger scale.

Making tostadas (a kind of toasted tortilla) on a ‘comal.’

Esperanza Martínez Onofre, another member of the kitchen team at Los Loosers, cooks tortillas until they are crisp (at this point they are called ‘tostadas’).

A tortilla tasting at Los Loosers restaurant. These tortillas are made the traditional way from scratch, from Tamoa’s sourced heirloom corn. Having been nixtamalized, painstakingly hand-milled and then hand-pressed with an array of local ingredients, this is slow, healthy food made with love.

Tacos at the affordable lunch spot, Ánimo in Mexico City. Tamoa supplies the masa for the two locations of this small fast food restaurant, popular with office workers. Customers can enjoy a quality tortilla, hand pressed, without noticing the nominal extra cost. Making good tortillas more accessible and common in the city is big part of Tamoa’s larger goals.

Change is possible. If you can get a good tortilla at this take-out window, there is hope for the future of the tortilla in Mexico!

Is there a way to get in contact with Tamoa?

but if SURROUNDED by GMO’s….. doesn’t matter does it? planet is consumed by them :'(