Food forests, an urban ag czar, and other signs of a local food renaissance in the capital of the Deep South.

I can attest to the traffic, and to the shopping malls, with their acres of barren asphalt broiling in the Georgia sun. But when I last lived in Atlanta, from 2009 to 2013, something else was afoot. Urban farms were sprouting from the cracks in the cement like kudzu.

There was one called Love is Love Farm in the co-housing community where I lived at the time – three acres that supplied much of the produce for the 65 households on-site. An agri-burb if you will. Another organization, called Truly Living Well, was cultivating tiny plots throughout the city, including Wheat Street Gardens in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward, a downtown neighborhood known as the birthplace of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr (they’ve since moved to a bigger location in a different neighborhood). Located atop four acres of concrete slabs – what was left after a housing project was demolished – these urban farmers were literally coaxing fruit and vegetables from the rubble.

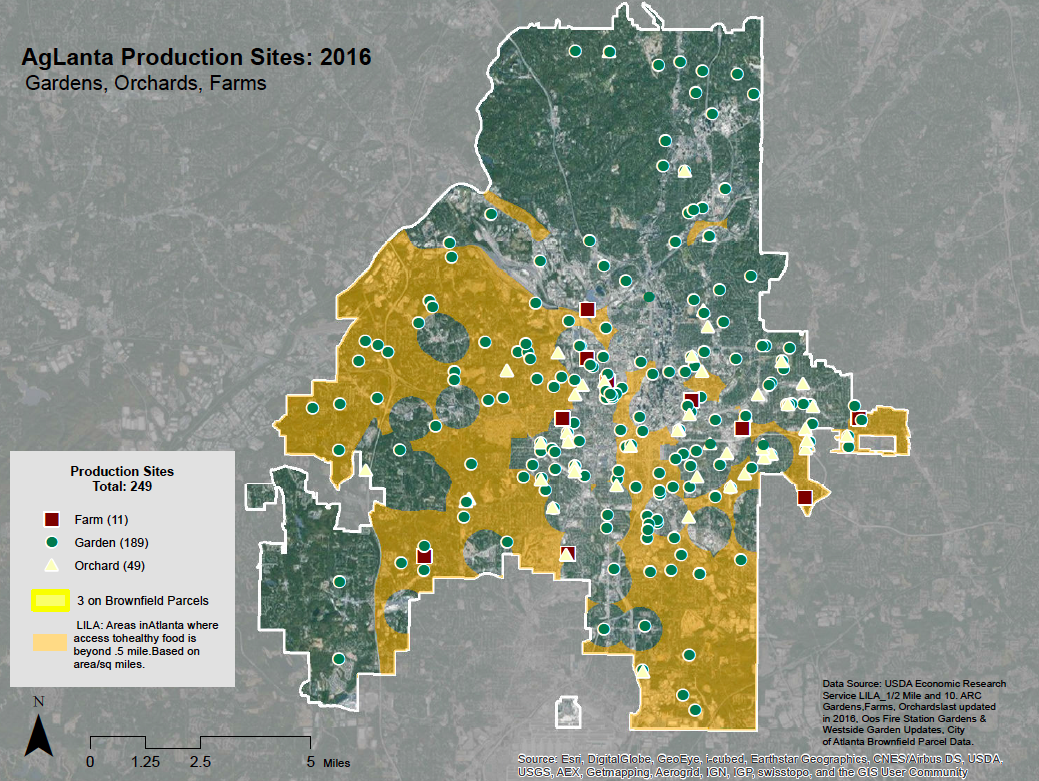

And during the last couple of years, the urban agriculture scene in Atlanta has exploded – there are now 11 farms, 49 orchards, and 189 community gardens within city limits, and scores more in the larger metro area.

“We want to make sure there is access to nutritious food – that’s not a can of green beans, that’s actual green beans.” – Mario Cambardella, Ag Czar of Atlanta

Sensing the momentum, the city hired an Urban Agriculture Director in December 2015 to act as a bridge between Atlanta’s eager urban farmers and the government bureaucracy, the first municipality in the country to create such a position. A modest backyard plot for personal consumption is one thing, growing for commercial purposes, another – one can’t go tilling up their front yard or putting a flock chickens out to pasture on vacant city lots without permission.

Mario Cambardella, the city’s appointee for urban ag czar, explains that until recently there were no official policies on urban growing in Atlanta (full disclosure: I went to graduate school with Cambardella). That changed in 2014 when the city passed its first ever urban agriculture zoning ordinance, which clarified official policy on the matter. The ordinance effectively condoned a wide range of urban growing operations, but it also enacted a few bureaucratic hurdles.

“We have three designations: farmers markets, market gardens, and urban gardens,” says Cambardella. “All of those need permits and a site plan.”

Those site plans could easily cost $2,000 to $3,000 from a professional. Cambardella, a landscape architect by training, is there to help start-up growers get around this potential roadblock. “In the last year I’ve helped five or six new farmers with professional site plans. They wouldn’t have been able to get started otherwise.”

Besides helping local growers navigate the permitting process, Cambardella is charged with coordinating the city’s long-term goals to boost the local food economy. Mayor Kasim Reed wants to put Atlanta on the map as an urban agriculture mecca. Upon his election in 2010, Reed learned that more that 53 percent of the city was classified as a “food desert” by the USDA – neighborhoods that lack a full-service grocer, and where most residents are too poor to afford a vehicle that would allow them easy access to more distant supermarkets.

AgLanta Production Sites 2016: Gardens, Farms, Orchards.

That year, Reed announced an ambitious goal: to bring “healthy food within a half-mile of 75 percent of all Atlanta residents by year 2020.” One way to do that is to encourage more grocery stores to open shop in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Another is to produce food directly in those neighborhoods. One of the key provisions of the urban ag ordinance was to make it legal for growers to sell food on-site, rather than trucking their produce to farmer’s markets and upscale grocers in wealthier parts of town.

Something is working because the swaths of food desert across the map of Atlanta are subsiding. In 2016 they were down to 36 percent of the city.

“There are a lot of ways to define a food desert,” says Cambardella, noting that gas stations and quickie marts that sell chips, candy bars, and the occasional apple don’t qualify as healthy food access. “We want to make sure there is access to nutritious food – that’s not a can of green beans, that’s actual green beans.”

Beyond the dozens of citizen-led farms and gardens that have sprung up in low income neighborhoods across Atlanta, there is a new city-sponsored project underway to address the food access issue: the Brown’s Mill Food Forest, a seven-acre swath of vacant land on the city’s south side that will soon be planted in fruit and nut trees, berry bushes, row crops and even edible mushrooms. More than a third of households in this predominantly African-American neighborhood are below the poverty line. The closest grocery store is a bodega two miles away, which offers only a small selection of fresh food.

Community support has been strong. Cambardella hosted an event in December to elicit input from the neighborhood. He supplied the barbeque, a local outfit called Get Your Goats Rentals provided their herd of brush-clearing goats to keep the kids entertained, and longtime residents provided stories. The seven acres, long ago enclosed by single family homes on half-acre lots, was one of the last farms remaining in the area as the city bulged outward in the fifties, Cambardella learned. Ruby and Willie Morgan, the deceased former owners, grew vegetables on a small scale, which they shared freely with their neighbors, as recently as the early eighties.

“The older neighbors told us that Mr. and Mrs. Morgan would put their extra vegetables in white grocery bags and tie them to the fenceposts for anyone who needed food to grab,” says Cambardella.

The property, which was slated to become a small subdivision until the bottom dropped out of the local housing market during the Great Recession, was purchased by the city with a matching grant from the US Forest Service’s Community Forest Program. The funding program is normally restricted to projects that protect natural areas in cities, but Cambardella says the Forest Service was intrigued by the idea of a food forest, which is modeled on a natural forest, but substitutes peaches and pecans in place of dogwoods and pine trees.

It was a tough sell at first, he adds. It’s the first time the US Forest Service has given a grant for an urban agriculture project, and the concept of a food forest isn’t exactly mainstream – Brown’s Mill will become only the third urban food forest in the country (the progressive bastions of Seattle and Austin lay claim to the other two). Though that may soon change.

“The older neighbors told us that Mr. and Mrs. Morgan would put their extra vegetables in white grocery bags and tie them to the fenceposts for anyone who needed food to grab.”

“It’s one of those things, when I first described it, nobody wanted to touch it,” says Cambardella. “Now everybody wants to be in on it. The U.S. Forest Service said ‘this is not only a project we want to fund, but one that we want to see through’. The National Park Service found out about the project and now they want to get involved.”

This spring, the city will put out a notice seeking urban farmers to steward the land. In the interim, Atlanta’s Green Youth Corps has been enlisted to clear brush, haul off trash and debris, and install irrigation lines and other infrastructure needed to get the project up and running. Cambardella says if all goes as planned, the first crops should go in the ground this fall.

And in the coming year, the city will embark on another, even more ambitious urban agriculture project. HUD, the federal government’s poverty-fighting urban development agency, awarded $30 million to Atlanta to help revitalize several west side neighborhoods in which 20 percent are unemployed and nearly 50 percent live beneath the poverty line. A significant chunk of those funds will be allocated to local food initiatives. The tentative name for the project is Aglanta West.

To keep the momentum burning, this month city hall is putting on the first ever Aglanta Conference, where local growers will gather to learn more about this and other opportunities expand urban agriculture across the city. Cambardella is working with city’s real estate department to determine which surplus city-owned properties may be suitable for food production. He’s identified ten so far, and plans to make them available at no charge to urban growers.

“We’re setting up a licensure agreement that will allow people to farm for three years, with an option to renew,” says Cambardella. “There will be certain criteria, like you have to have insurance, but otherwise it will be first come, first serve. This all stems from my first meetings with constituents. They said ‘we really need access to land, that’s what we really want’. So that’s what we’re working on.”