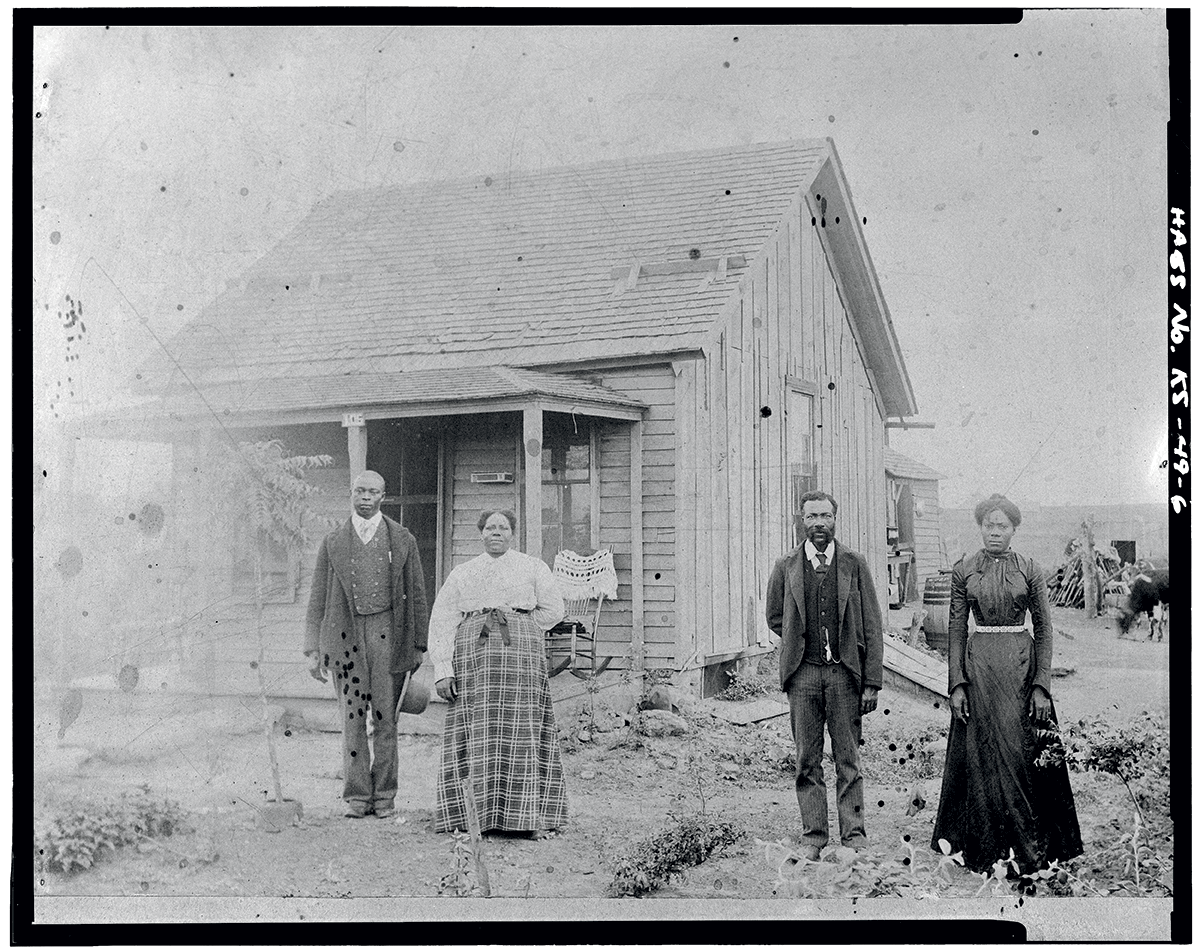

After the Civil War, freed slaves from Kentucky headed west to Kansas and established their own agricultural community, named Nicodemus. Nearly150 years later, the descendants of the town's very first farmers are doing everything possible to keep their legacy - and land - alive.

GILLAN ALEXANDER’S SEED DRILL is on the fritz. So the winter wheat he’d hoped to get in the ground this early-October morning will have to wait until a parts dealer more than 80 miles away locates the necessary ball-bearing housings. Alexander, 59, who also grows sorghum and soybeans in rural Nicodemus, Kansas, puts the hassle in perspective: “My grandfather farmed wheat here using mules. I’m grateful to carry on that tradition, though it’s hard, even with modern equipment, and it does put pressure on me. I feel like I need to do an exceptional job, not only because that’s what farmers do, but because I’m one of the few black farmers left – in this town, the state, and the nation.”

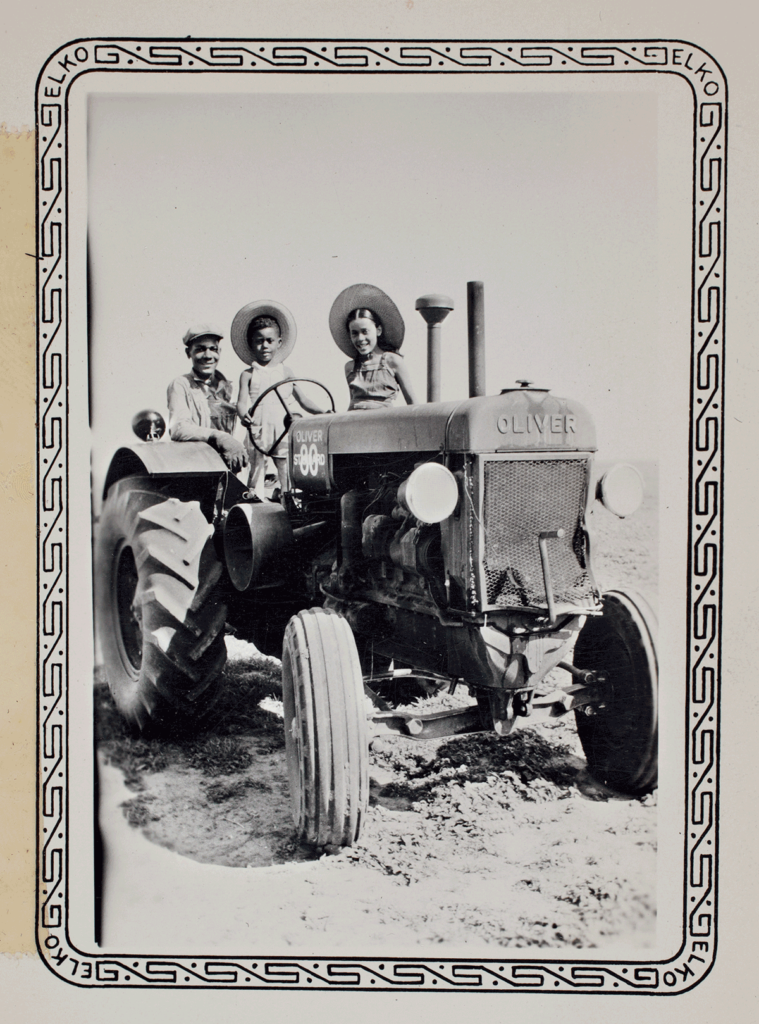

Local historian Angela Bates dates this archival image to the 1940s.

Alexander’s 1,100 acres include many that his great-grandfather, Andrew Alexander, farmed during the late 19th century, after migrating to northwest Kansas from Kentucky – one of 330 emancipated African Americans heeding the call of an 1877 circular promoting “The Largest Colored Colony in America.” That colony, established by six black men and a white land speculator, took its name, Nicodemus, from an 1864 song written by an abolitionist.

“Nearly a hundred years before Martin Luther King Jr. had a dream, our ancestors were living the dream,” says Gil Alexander’s cousin Angela Bates, executive director of the Nicodemus Historical Society. In the 1880s – a time when many blacks were sharecroppers – the citizens of Nicodemus presided over a booming agricultural economy, with more than 3,000 acres yielding corn, wheat, potatoes, sorghum, and other crops. A population of 650 supported a schoolhouse, post office, bank, two news- papers, two hotels, and three churches. Nicodemus wanted to expand that list with a railroad station. Instead, the Union Pacific chose an alternate route, five miles to the south, in the spring of 1888.

Bates led the charge for Nicodemus’ designation as a National Historic Site. Of her ancestors who settled here, she says: “They endured slavery. The least we can do is not forget.”

Within months, a mass exodus occurred, as businesses, and then families, relocated to be near the new depot. Adding eventual insult to that initial injury? The Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. By the 1960s, the town claimed only 40 residents, and even the post office and school had shuttered. Nicodemus could have gone the way of the 11 other black agricultural colonies founded in Kansas after Reconstruction – all now extinct. Those places, however, didn’t have a descendant like the force of nature that is Angela Bates.

During the 1970s, Bates was working as an interior designer in Washington, D.C., when a friend at the Department of the Interior told her that if Nicodemus were designated a National Historic Site, the National Park Service would take charge of maintaining the town’s neglected municipal buildings. “I grew up in California but visited my relatives in Nicodemus every summer,” the 64-year-old says. “There were chickens, pigs, cows, and horses. I always wanted to stay. I felt so proud of it.”

Gillan Alexander farms sorghum, as well as wheat and soybeans, on 1,100 acres, some of which have been in his family since the 1870s.

Bates finally moved to the area in the late ’80s and actively took up the cause of preserving it, launching the Nicodemus Historical Society and creating an archive at the University of Kansas to house the documents and photographs she had collected. In 1991, she wrote to Kansas senator Bob Dole, who secured funding for a Park Service feasibility study. And five years later, President Bill Clinton signed a bill into law making Nicodemus a National Historic Site.

It was a major victory, if not the town’s saving grace. Both Bates and Gil Alexander, who helped organize the Kansas Black Farmers Association in 1999, see agricultural and historical tourism as the way forward. Unfortunately, though, the infrastructure necessary to support visitors doesn’t exist. Nicodemus is 225 miles away from the nearest major airport, in Wichita, and 50 miles from the Interstate. There’s not a single hotel and only one restaurant, a BBQ joint named Ernestine’s that Bates opened and operates herself.

Arthur Warren White surveys one of his Nicodemus wheat fields in the late 1940s or ’50s.

“We’ve got plenty of acreage, but not a lot of people,” she says. The population currently stands at 19, and most of those folks are far from spring chickens. Retired farmer Florence Howard, 86, remembers her grandparents, George Moore and Effie Johnson – former slaves and two of Nicodemus’ original settlers – planting long-neck squash, blue crowder peas, and sweet potatoes. “They farmed mostly with their hands, because they didn’t have machinery,” Howard says. Johnson’s skin bore the marks of a Kentucky master who whipped and raped her. “She had a cut above her hip and wore that scar to her grave. There’s nothing left of George and Effie’s house except a pile of stones down Highway 24.”

ABOVE Retired farmer Florence Howard is the granddaughter of George Moore and Effie Johnson, among the freed slaves who first migrated to the Kansas town.

Another direct descendant, Dr. JohnElla Holmes, recently moved back to town at Bates’ urging. “Angela’s dragging us all back here and motivating us,” says the 60-year-old, a former assistant professor at Kansas State University’s College of Education and the current executive director of the Kansas Black Farmers Association. Holmes also runs an agriculture camp in the town to expose inner-city kids from across the country to people like Gil Alexander. “Our mission is to grow new farmers and get them excited about conservation and learning how to feed their families,” she explains. “You feel your worth just being connected to Nicodemus. It’s such a beautiful birthright, and farming’s at the heart of that. It’s our responsibility to make sure our children and grandchildren know this history.”

Abandoned farm equipment rusts in a Nicodemus field.

Holmes’ daughter, LueCreasea Horne, may be the torchbearer her elders long for. The 38-year-old came home a few years ago with her husband and two children.

“It’s time for the younger generation to step up and keep Nicodemus going,” Horne says. She worked as a National Park Service guide here for three consecutive summers during college and dreams of someday overseeing the site as superintendent. “One way or another,” Horne insists, “Nicodemus will survive.”

This shot of three young women on a Nicodemus farm was likely taken in the 1940s.

Gil Alexander hopes she’s right. “I don’t have any kids. I don’t know what’s going to happen,” the fourth- generation farmer says. “There have been times when I’ve come close to saying, ‘To hell with this, I’m done,’ but then I think about the ones who came before. What kept them going? Our heritage. You can’t really explain that. You have to feel it. You have to have a passion for it. This is what built America, working the land.”

Dr. JohnElla Holmes (left), a retired college professor, recently returned to Nicodemus, where she runs an agricultural camp for kids. Her daughter, LueCreasea Horne (right) moved back a few years ago to raise her two children, including daughter Lauryn.

Thanks

good luck.

I am planning to come to nicodemus in July for your celebration. I am eager to meet descendants who can tell me about the town