The Oregon city boasts the nation's most in-demand housing market. But is a law that protects adjacent farmland strengthening or strangling the famous food mecca?

The annoying part, Rod Park tells me, is the constant phone calls. We’re lurching across Park’s Nursery in his truck on a rainy Saturday, casually discussing a 1978 Oregon land-use law that has started to consume his life.

A third-generation grower, Park owns 40 acres in the town of Gresham, 12 miles east of downtown Portland. His wholesale nursery is close enough, just barely, to fall inside Portland’s urban growth boundary (UGB), a line surrounding the metropolitan area that determines where, precisely, land can be developed – and where it cannot. State law requires that each Oregon municipality essentially draw a circle around its perimeter. Inside go the neighborhoods, condos, coffee shops, Thai restaurants, movie theaters, and every other type of residential or commercial development that a healthy urban center needs.

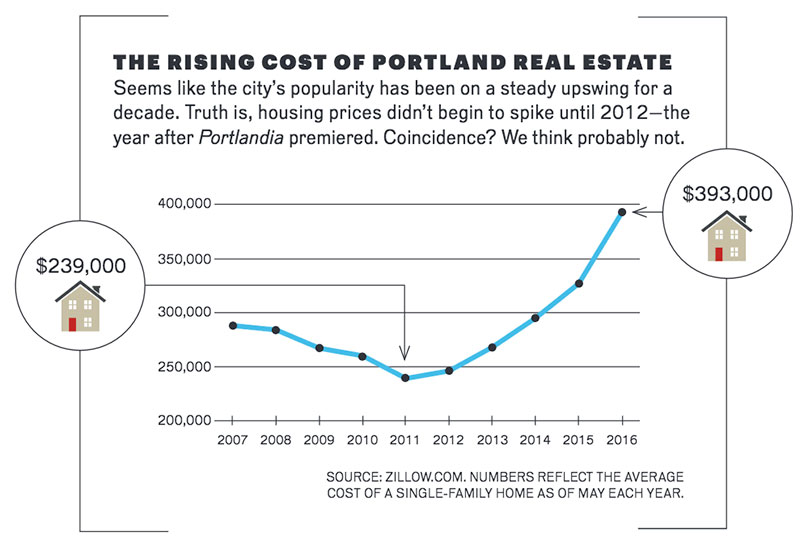

When Portland established its UGB nearly 40 years ago, Park’s father protested his nursery’s placement inside. But the demarcation never wound up mattering much – until housing prices began to explode in recent years (see “The Rising Cost of Portland Real Estate,” below). If Park wanted to, he could sell his property to a developer. The nurseryman’s neighbor, on the other side of the boundary, doesn’t have that option. Mere inches separate them geographically; financially, the gulf couldn’t be wider. In 2010, Demographia, a public-policy think tank, reported that land tucked within the UGB was worth roughly 11 times more than that just beyond it ($180,000 versus $16,000 per acre).

It’s as if an invisible “For Sale” sign stands in front of Rod Park’s nursery. “I get approached by developers all the time,” the 62-year-old says. “I actually need to hire someone to take the calls.

Nurseryman Rod Park sold a portion of his acreage, which sits just inside Portland’s urban growth boundary, to developers in 2005. A subdivision now abuts his property line.

Only two other states, Washington and Tennessee, have adopted similar legislation, though more than 100 individual cities now employ the strategy, according to the American Planning Association. “From an urban land-market point of view, rural land or farmland is simply urban land in waiting,” explains Ethan Seltzer, a professor of urban studies at Portland State University. “What urban growth boundaries do is interrupt that notion and say, no, wait – this landscape is not urban land in waiting, and we are going to protect it.” UGBs constrain a metropolitan area’s footprint, preserving the surrounding greenbelt, while also midwifing a dense, desirable, cyclist-friendly city into existence.

In Portland, you can drive south on Interstate 5, cross the Willamette River, and find yourself, abruptly and gloriously, surrounded by rows of vegetables, hops, and hazelnut trees. Farmers benefit from the close proximity to a desirable market, sans the higher city property tax and minimum wage. Affluent urbanites gain easy access to nature and 50-plus CSA farms and some 60 farmers markets. One could argue that Portland owes its hyper-local food scene – endearingly spoofed on the TV series Portlandia – to the UGB.

Of course, any such boundary is only as strong as the political will that guards against development. Although Portland has voted to widen its UGB more than 35 times, the area inside it has increased only 14 percent, while the population has jumped a whopping 61 percent.

Second only to Portland in terms of rapidly appreciating real estate, Seattle fosters a similarly anti-sprawl political climate. Earlier this year, the Seattle Times editorial board published a scathing rebuke against expanding the Emerald City’s UGB. “The boundary is not a relief valve to be opened when the going gets tough,” the op-ed proclaimed. “Rather, it’s there to preserve permanently the region’s vital diversity of land uses, habitat, and rural economic activity.

At a much more micro level, drawing the line can put average citizens through hell. Lyle Spiesschaert, 69, who grows wheat, crimson clover, and hay on a farm founded by his grandfather 30 miles west of downtown Portland, says he supports UGBs in theory. But the original boundary bisected his family’s property. In 2003, they finally acquiesced to encroaching developers, selling the portion within the perimeter – only to learn, 12 years later, that their remaining 200 acres would be sliced in half again as the UGB expanded, a decision, says Spiesschaert, that was “made behind closed doors.”

“My brother and I run the farm, and we’re very connected to the earth,” he adds. “Our philosophy is about sustainability, not greed and money. That’s not the kind of legacy that we want to leave.”

Spiesschaert would prefer not to cash in and watch another sub-division go up in his fields. For him, however, the pressures are more than financial. Residential neighbors complain to authorities about noise from Spiesschaert’s farm, and have even accused him of spreading “poison” (actually innocuous soil amendments, like agricultural lime). “The bureaucrats will tell you that you can keep farming, even if your land falls inside or right outside the line,” he says. “But in my experience, the interface between rural and urban is problematic.”

One could argue that Portland owes its hyper-local food scene – endearingly spoofed on the TV series Portlandia – to the urban growth boundary.

The UGB concept has no shortage of critics, among them wannabe “gentleman farmers” interested in five acres outside of town. Which is why some parcels beyond Oregon’s UGBs have been designated as EFUs – exclusive farm-use zones – requiring a minimum lot size of 80 acres and at least $80,000 in annual gross sales.

The most persuasive anti-UGB argument alleges that the boundaries doom affordable housing. “Yes, we’re preserving farmland, but we’re paying a tremendous price for it,” explains Dave Hunnicutt, president of Oregonians in Action, a property-owners’ association that seeks to reduce land-use regulations. As property values continue to climb, developers no longer bother with small homes, instead building McMansions and setting off a vicious cycle of escalating real estate.

Counters Jim Johnson, land-use coordinator for the Oregon Department of Agriculture: “The real reason Portland-area housing is so expensive is our quality of life. People want to live here. What would change that? If we start sprawling and becoming one of your typical California cities, where it takes three hours to drive 20 miles.”

Rod Park sold 22 acres in 2005, and now vinyl rooftops loom over the conifers bordering his nursery. We drive through the subdivision and marvel at the maze of homes. He points to a paved walking trail. “That used to be my dirt service road.” As Park gets older, the future of his business presses in. He commiserates with Spiesschaert’s lament about sharing a property line with tract homes. Park would like to use a shotgun to kill rabbits, for instance, but the city forbids it.

His wife has been ill, and he knows a cushy retirement remains one phone call away. Then again, the responsibility of being the third man in his family to run the nursery is not something he takes lightly. So what would Park have done, back in 1978, if the decision had been his? Would he have preferred to be inside or outside the urban growth boundary? He pauses, watching suburban traffic thunder down 282nd Avenue. “It’s a hard choice, and one I’m glad I didn’t have to make.”