Colorado's tug-of-war over water rights boils down to the haves...and the have-nots. So who wins, now that scarcity is the norm?

In beer commercials, Colorado beckons as the state of cool mountain streams and thunderous waterfalls, but the 1820 expedition sent to survey the high plains following the Louisiana Purchase dubbed the area the “Great Desert” – unfit for cultivation and uninhabitable for people dependent on agriculture to survive. Paradoxically, both extremes hold true. Those Coors ads depict the Rockies of western Colorado, where roughly 80 percent of the state’s precipitation falls on ski-resort towns like Steamboat Springs and Telluride. To the east lies the aforementioned “desert” and 90 percent of the population, mostly in booming Front Range cities such as Denver, Pueblo, and Colorado Springs.

The Gunnison River, a tributary of the mighty Colorado, stretches more than 160 miles through the state’s western side.

Ever since the state became a state, its government and our federal one have grappled with how to redistribute the bounty – bankrolling dams, reservoirs, and massive transmountain diversion tunnels, up to 23 miles long. In Colorado, water itself is treated like private equity. Due to the particulars of an antiquated law, the first people to put water to “beneficial use” get dibs. And because pioneers predate almost everybody else, today’s farmers and ranchers control 85 percent of the available water supply. Sustained droughts, depleted aquifers, global warming, and a rapidly growing population have made scarcity the norm. As a result, farmers find themselves sitting on a commodity worth far more than their crops or land.

During the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, nearly all of the farmers in Crowley County, southeast of Colorado Springs, participated in what are known as “buy and dry” deals, selling their water rights to growing municipalities and retaining the land, albeit unirrigated and unable to support crops. Once farming tapered off, production at the local cannery ground to a halt. Feedlots closed. Mills shuttered.

In arid Morgan County, northeast of Denver, Matt Padilla manually dams up a flood irrigation ditch using a tarp and 2x4s.

Colorado’s northwestern Yampa River Valley boasts so much water that its farms, like this one near Hayden, seldom have to “make a call on the river,” i.e., invoke the seniority of their water rights.

Photographer Matt Nager, who shot the images here, was deeply affected by what he saw in Crowley. “The town of Ordway, the county seat, used to have a car dealership, a movie theater, and several grocery stores,” he says. “Those are all gone. In fact, most of the downtown shops are boarded up.” The few farmers who remain must face the consequences of being left behind. Forget about beneficial runoff from nearby fields. Dust storms sweep across abandoned land, clogging active irrigation channels, and giant tumbleweeds fill up barns. “This once-thriving county shows how short-term choices can lead to bad long-term water planning,” explains Nager. “It’s a warning of what not to do.”

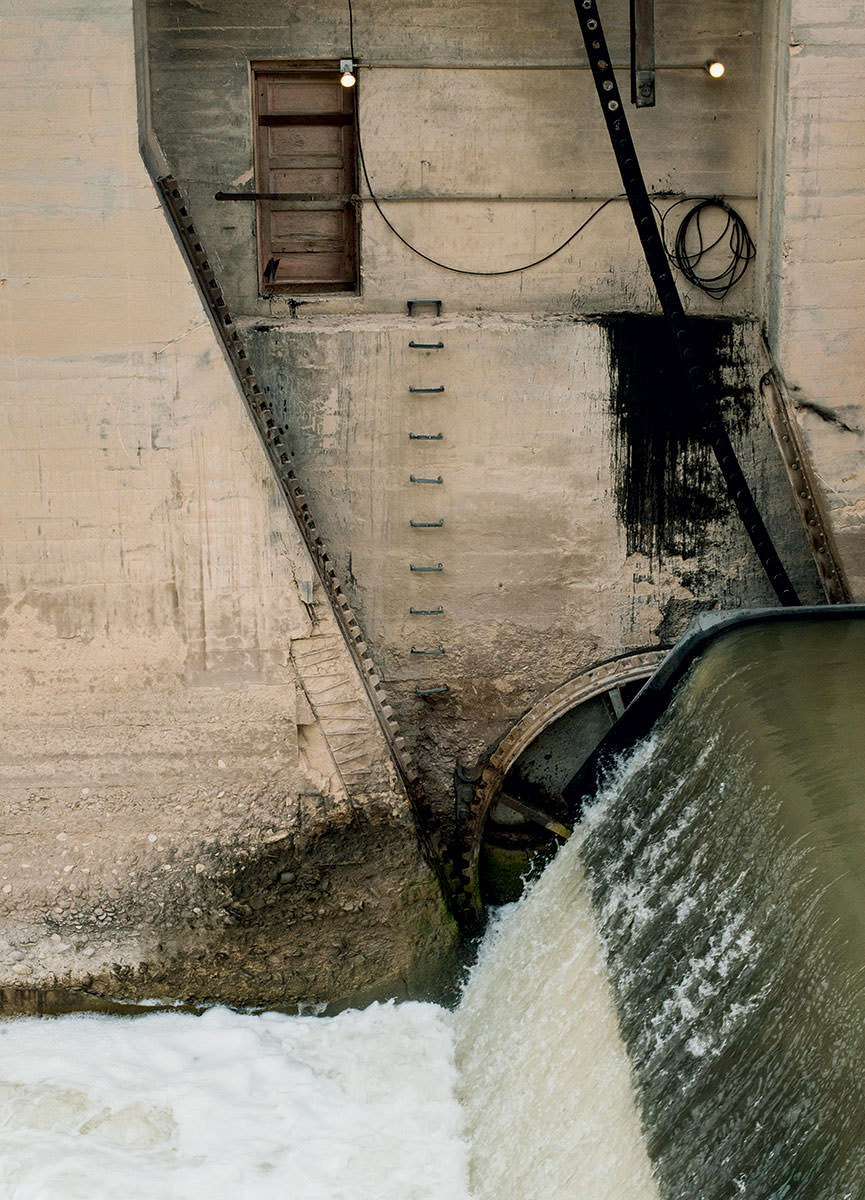

The Federal Bureau of Reclamation finished constructing the Grand Valley Diversion Dam, which redirects water from Colorado’s wet Rockies to parched farmland, in 1916.

Robert Sakata uses this center-pivot system (basically a huge rotating sprinkler on wheels) to irrigate his 2,500 acres in Brighton, CO. The once-rural town has become a suburb of Denver, and while many farmers resent the development, Sakata sees an upside: “Interest in local produce is what keeps us going.

So what should Colorado do? Lawmakers have long viewed water rights as the third rail of local politics. Take a position, and you risk being deemed anti-agriculture or anti-growth. But last year, the state released its first-ever comprehensive plan for managing the crisis. The promising 540-page roadmap, championed by Governor John Hickenlooper, outlines conservation methods and brokers several new approaches. Legislation based on the bipartisan report is already beginning to take shape: In May, the governor signed House Bill 1228 into law. Officially called the Ag Protection Water Rights Transfer Mechanism, it states that, rather than selling water rights forever, farmers can lease them to municipalities for shorter periods of time. Other recommendations have yet to morph into policy, though the plan foresees a future in which cities might, for example, provide funds to help farmers transition to more drought-tolerant crops.

Pragmatic eastern farmers, accustomed to drought-related challenges, seem more eager to forge cash-generating solutions than their western counterparts. For the plan to work, both sides of the state – and the issue – must continue to compromise. Denial has long governed Colorado’s water-management strategy. But eventually, everyone has to reckon with the realities of settling in the desert.

Drive through Crowley County today, and you’ll find abandoned farmhouses, like this one, and dusty, barren fields. Only some 6,000 acres – of 60,000 once in production – remain active.

Darla and Harry Wyeno of Crowley County, CO, sold their water rights for $1,050 per share in 1976 to send their two children to college and pay off a farm loan. “It seemed like a lot of money back then,” says Darla. Those shares would now fetch $25,000 apiece, which adds to the sting, she explains, of “watching the community you’ve loved all your life go downhill.”

great pics