Bees aren't just great at pollinating and making honey. Turns out they make great guinea pigs too.

Every so often members of Congress love to trot out examples of what they feel is wasteful government spending (almost exclusively from the arts, humanities, and sciences) and hold them up for ridicule. Hey, we understand. It’s much easier to make fun of something than actually take the time to understand the reasoning behind it.

The latest politically-motivated media opp of this sort happened in May when U.S. Senator Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) issued an oversight report called “Twenty Questions: Government studies that will leave you scratching your head” that featured the kind of flashy cover art more often found on a comic book than a government report. One of the scientific studies lambasted by the Senator was on the creation of a honeybee sting pain index by Cornell graduate student Michael L. Smith. But like the following four other scientific studies involving bees, even seemingly strange research can pave the way for breakthroughs in a variety of fields and spur innovation.

The cover of a Senate oversight report on scientific research. Image via U.S. Senator Jeff Flake’s website

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Better Him Than Us[/mf_h2]

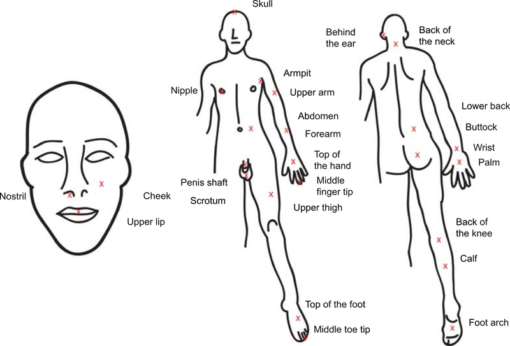

Smith stung himself with honeybees on 25 different locations on his body to determine the differing pain levels. The 2014 study, “Honey bee sting pain index by body location,” determined location-based pain perception isn’t necessarily consistent with places on the body with the thinnest skin or that have the most sensory neurons, which could be useful in studying how and why we perceive pain as we do. Smith’s work built upon the research of Justin Schmidt, a biologist, research director of the Southwest Biological Institute, and creator of the Schmidt Sting Pain Index, which measures the painfulness of various insect stings. The most painful places to be stung, according to the study, were inside the nostril, the upper lip, and penis shaft. The skull, middle toe tip, and upper arm were the least painful spots.

Diagram of body parts where researcher Michael L. Smith stung himself with honeybees. Illustration via PeerJ

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Bees on Blow[/mf_h2]

Building on a 2009 study by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign on how cocaine effects honeybees, researchers from Macquarie University, in Sydney, Australia, and Washington University in St. Louis, examined whether honeybees developed a preference for a location where they received cocaine and whether the drug affected their foraging activities, among other behaviors. The 2014 study, “Cocaine affects foraging behaviour and biogenic amine modulated behavioural reflexes in honey bees” published on PeerJ, found cocaine does indeed affect these behaviors. Coked-up bees showed a preference for a feeding location and upped their number of visits at a sucrose feeder. The researchers determined that cocaine alters reward responses across divergent animal groups with the possibility that invertebrates, like the honeybee, could be used to study the behavioral impacts of cocaine, and possibly other drugs abused by humans.

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Caffeine Puts the Buzz in Bees[/mf_h2]

In another study involving giving bees stimulants, researchers from the University of Sussex trained two groups of bees to go to two different feeders, one containing caffeine in the same amount found in many flowers. The results were similar to the behavior exhibited by bees on cocaine: caffeinated bees visited the feeder more often than the other bees. The caffeine also affected the bees’ perception of the quality of the nectar (coked-up bees had the same problem in a 2009 study). The 2015 study, “Caffeinated Forage Tricks Honeybees into Increasing Foraging and Recruitment Behaviors,” in Current Biology, found the relationship between the flowers with caffeinated nectar and bees was exploitative rather than mutually beneficial since caffeine led to behavioral changes that served the plants’ needs, but made bee colonies less productive.

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]They Must Be Huge AC/DC Fans[/mf_h2]

A 2015 joint study by the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, University of Adelaide, Harvard University, and University of California, Davis compared the pollination techniques of Australian native blue banded bees with the North American bumblebee. While the bumblebee, which is used for commercially pollinating tomato plants, grabs onto the part of the stamen that contains the pollen on tomato flowers and shakes out the pollen, their Aussie counterparts were found to bang their heads against the flowers up to 350 times a second resulting in pollen bursting into the air. By recording the audio frequency and duration of the bees’ buzz, the researchers were able to determine that the Aussie bee vibrates the flowers at a higher frequency than the bumblebee and spends less time at each flower. According to the researchers, the discovery could help improve the efficiency of crop pollination, and even has the potential to impact our understanding of muscular stress and help in the development in miniaturized flying robots.

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Bees Can Be Negative Nellies, Just Like Us[/mf_h2]

When we have negative feelings, we have a tendency to exaggerate the likelihood that negative things will happen to us. Research showed that rats and dogs, as well as birds, displayed a similar tendency. But researchers from Newcastle University, in England, wanted to see if the same held true for invertebrates. They trained honeybees to associate a certain smell with a positive reward and a second smell with a punishment. When they agitated the bees by shaking them, simulating a predatory attack, the bees treated a third, neutral stimulus, as a punishment. The 2011 study that appeared in Current Biology suggested for the first time that bees can be regarded as exhibiting emotions, according to the researchers.