It's a tense time for mink farmers like the Papes.

When I first contacted Jan Pape, the skepticism in his voice was palpable.

A farmer of domesticated American mink (Neovison vison) since 2001, he’s used to having his work sensationalized in the public sphere with some regularity. So asking to come to his farm with a Nikon in hand meant I had to build a modicum of trust.

I promised I was in no way affiliated with PETA, and we made an appointment to sit down and chat over a cup of coffee at his farm, along with his wife and co-farmer Helle.

While the conversation started with the practical aspects of fur farming, it inevitably drifted towards ethics. I got the sense these were two people who were very proud of their work, regardless of how controversial it may be.

It’s a tense time for mink farmers like the Papes. Their farm is just an hour’s drive southeast from the epicenter of the outbreak of Aleutian disease – also known as mink plasmacytosis – which hit the Danish fur industry hard this year. The outbreak was first reported in October 2015, but by November, it had decimated 130 farms in Holstebro, the region with some of the largest operations in the country. At least 700,000 animals have been culled and pelted in Denmark, and the virus is still on the move.

Discovered in 1956, this parvovirus is transmitted through bodily fluids of infected hosts, but can lay dormant in the soil for years. The symptoms for mink resemble systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in humans, and the disease travels with vectors such as workers, feed, and various wild riparian-dwelling carnivores.

Mink burdened with the virus have fewer or no young, low-quality pelts, and an eventual 100-percent mortality rate.

The first farms infected used the same regional Danish Mink Feed (Dansk Pelsdyr Foder) facility. Early investigations into the origin of this year’s calamity pointed to a shipment of Polish fish: 90 percent of wild Polish mink have the virus, and one individual hitchhiker could theoretically infect a whole shipment of feed.

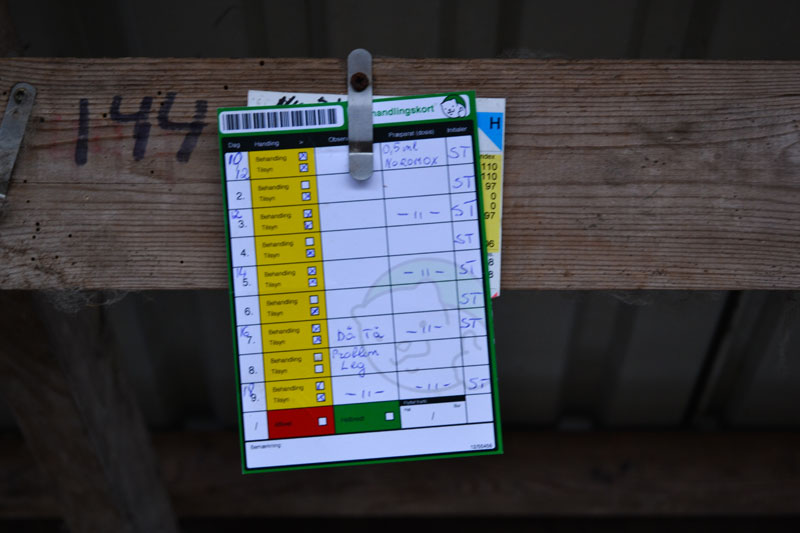

Veterinary health checkups have always been constant in fur farming, as beautiful pelts only come from healthy animals. They’re more pressing now: blood tests are taken from each animal four times a year.

Sander Jacobsen, director of Public Affairs for Kopenhagen Fur, the auctioning cooperative owned and managed by Danish Fur Breeders’ Association, wrote in an email that: “… we are very close to not having the disease in Denmark, because of a fantastic veterinary programme carried out since 1978. What we see right now in Holstebro is certainly a severe setback, especially for the farms hit by the virus, but in the long run the whole thing will only appear as a minor disturbance on the curve towards zero Aleutian disease in Denmark.”

Indeed, according to the the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration, in 1976, 100 percent of Danish mink farms had animals infected with the virus, but aggressive veterinary management, along with improved welfare and hygiene, have affected a steady decline in recent decades.

Since plasmocytosis hasn’t hit their medium-size operation yet, the Papes are currently currently housing 1,500 extra animals (of 2,800 total). They’ve sacrificed the respite of the low winter season (the time between pelting and when new young – called kits – are born) to host animals from regions that are near known outbreaks. Their farm doesn’t share immediate borders with other mink farms, so their isolation provides a margin of comfort.

Nonetheless, when it came time to tour the facilities, I had to put on a pair of their rubber boots from the shed: It’s not an outright quarantine, so much as a state of caution.

The majority of operations in the country are like this one: family farms with a few seasonal employees, rather than large factory enterprises. The fur farming industry directly employs 6,000 people in Denmark, 1,500 of whom are farmers.

Denmark has been a leader in breeding and veterinary science for mink for decades now, being the producer of 17 million pelts a year, out of 50 million sold globally. Danish farms are known to produce the largest portion of the highest-quality pelts, selling for 20 to 30 percent more than mink pelts from other nations.

While some may attribute part of that success to an optimal climate for raising mink, Jan believes it is primarily because he and his peers share information and materials, have access to excellent infrastructure, and communicate through the Fur Breeders’ Association – it’s a sort of quintessentially Danish worldview that emphasizes strength through cooperation.

In disease’s wake, the farmers pool something of an insurance through the cooperative – collected by a nominal per-pelt fee in previous years’ sales – in order to cover some of the losses experienced by those hit hardest; they also sell back animals to those farmers at below market price.

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]THE ETHICS OF FUR FARMING[/mf_h2]

Even if the virus turns out to be a mere disturbance to business as usual, there are other challenges looming for mink farmers.

The animals are cute, curious, rather intelligent, and are used to produce a non-food item, so fur farmers like the Papes are a perennial target for animal-rights activists. The disease outbreak only serves to put their work in the spotlight.

Jan and Helle believe it’s much easier to campaign for the welfare of something resembling a pet ferret than it is for the rights of a pig, and since a mink coat is fundamentally a luxury item, fur farming is a form of animal agriculture that even the most unrepentant of carnivores can come to oppose. The market shifts with the public sentiment.

Fur farming is a form of animal agriculture that even the most unrepentant of carnivores can come to oppose. The market shifts with the public sentiment.

Helle in particular emphasized that no one who knew her as a child would have pictured her in this line of work; she was always the first to knock on doors in her rural community when someone left a pet dog or cat out in the rain. Her love of animals is what she believes makes her good at her job.

Her gift for husbandry pays dividends: the Papes’ product normally sells for 18 to 20 percent above the average price for Danish skins.

Part of this price point also comes from the colors they produce: in nature, mink are tawny or dark brown, but breeding on fur farms has brought about 25 natural shades and patterns. Lighter shades of fur like “platinum” and “pearl” arose in the 1930s and 1940s, and animals with these mutations were subsequently crossed. The very rarest of shades today – called “blue iris cross” and “violet cross” – are white with a grey accent.

Pelts from various farms are sorted by color, quality, and sex, and then pooled into lots for auction five times a year at Kopenhagen Fur. It’s the world’s largest auction house for raw skins, and the only one that is ISO-9001 certified, a certification that takes into account the well-being and health of the animals, breeding conditions, farm hygiene, and other factors. Between 500 to 700 global fashion buyers spend up to about $290 million on skins in a single three- to eight-day event.

But unfortunately, the care of animals is not a pressing concern for the majority of current buyers, who hail from Eastern Asia (especially Hong Kong and China); China is also a major mink producer, but can’t match the quality of the Danish product. According to Jan, this has a lot to do with lax standards for animal welfare.

Before this years’ plasmocytosis outbreak, the average Danish mink farm posted an annual profit of $406,500. The results of the first auction of the year, however, have not been promising. As of January 2016, the per-pelt average price fell from 610 kroner ($91) in 2014, to 227 kroner ($34). Considering each animal costs around 140 kroner ($21) in food each year, the profit margin will be narrow this year, if it exists at all.

In the nearby Netherlands – the world’s third-largest producer of mink pelts – fur farming is set to be totally phased out by 2024 due to welfare concerns. Germany has recently introduced similar legislation.

Jan and Helle don’t see this as a thinning of the competition; instead they’re worried about the future of fur farming in Denmark.

For all the opposition, it’s an oddly sustainable industry. Mink are fed on bycatch from fishing and leftover meat from other animal agriculture enterprises: they’re the garburators of the animal husbandry world. Nonetheless, Jan asserts “they don’t eat anything that wouldn’t be good enough for a human.”

Before pelting, the animals die peacefully, going to sleep from carbon monoxide poisoning. Once the animals are pelted, their fat can be rendered into an oil for use in cosmetics and the treatment of leather, and their carcasses are used in the production of biofuels; mink carcasses even power some of the busses in Denmark’s second-largest city, Aarhus.

To improve goodwill towards the industry, in 2007, Kopenhagen Fur and the Danish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Dyrenes Beskyttelse) voluntarily partnered to make the welfare regulations for mink stricter in Denmark than they are in the EU at large, with provisions for better accommodations and health standards. The latter party, however, was not satisfied with the negotiations.

Birgitte Damm, chief advisor for the animal rights group, wrote in an email: “[we] pushed for the current legislation as a first step, but the agreement was that this should be accompanied by further work towards alternative extensive housing and production methods with better animal welfare: work that Kopenhagen Fur turned out to be unwilling to do, and a goal they were unwilling to pursue. Therefore collaboration stopped. Dyrenes Beskyttelse does not think that the current legislation provides good animal welfare, far from it.”

Her organization would like to see fur farming phased out in Denmark as well.

Ultimately, whether or not the Papes will be able to continue with their enterprise depends not on a virus, but on whether or not European consumers are still willing to consider a mink coat a luxury and an ethical one at that.

Further, the fur industry suffered a PR fiasco in 2010, when the chairman of the Danish Fur Breeders’ Association, Erik Ugilt Hansen, was charged with animal cruelty, after a hidden-camera gonzo television series called Operation X – orchestrated by another animal rights group called Anima – filmed conditions on his farm.

Even more “hands-on” activists have gone so far as to set these North American mustelids loose into the Danish nature, where they wreak havoc on ecosystems. In 2011, 3,000 animals were set loose from a farm on the island of Fyn. According to Damm, Dyrenes Beskyttelse, “do[es] not endorse this, and we speak out against it. It does no good for the animals released, for the local fauna or for the political goals we are pursuing.”

Those animals that survive escape and establish territory have been breeding in Europe for decades, and targeted by conservationists for eradication. Populations of formerly-farmed American mink have been linked to decline in native rodents like desmans and water voles in parts of Europe, and affected a decline in the critically-endangered and distantly-related European mink in its remaining Baltic range.

Ultimately, whether or not the Papes will be able to continue with their enterprise depends not on a virus, but on whether or not European consumers are still willing to consider a mink coat a luxury and an ethical one at that. Fur farming is losing legal traction in the EU, and Denmark remains as one of the last remaining strongholds.

Jan and Helle seem to have a cautious optimism, believing that hard work, decent conditions for their animals, and a consistently high-quality end product will allow them to weather the highs and lows of the market. They’ll have the strength of their convictions tested at auction this year.

this industry is hideous and exposes the most despicable side of humanity

I wish the Papes success, they seem to be committed to their work.

Ah, peaceful death by gassing. Reminds me of something…