The Falkland Islands are a wildlife sanctuary turned organic farm

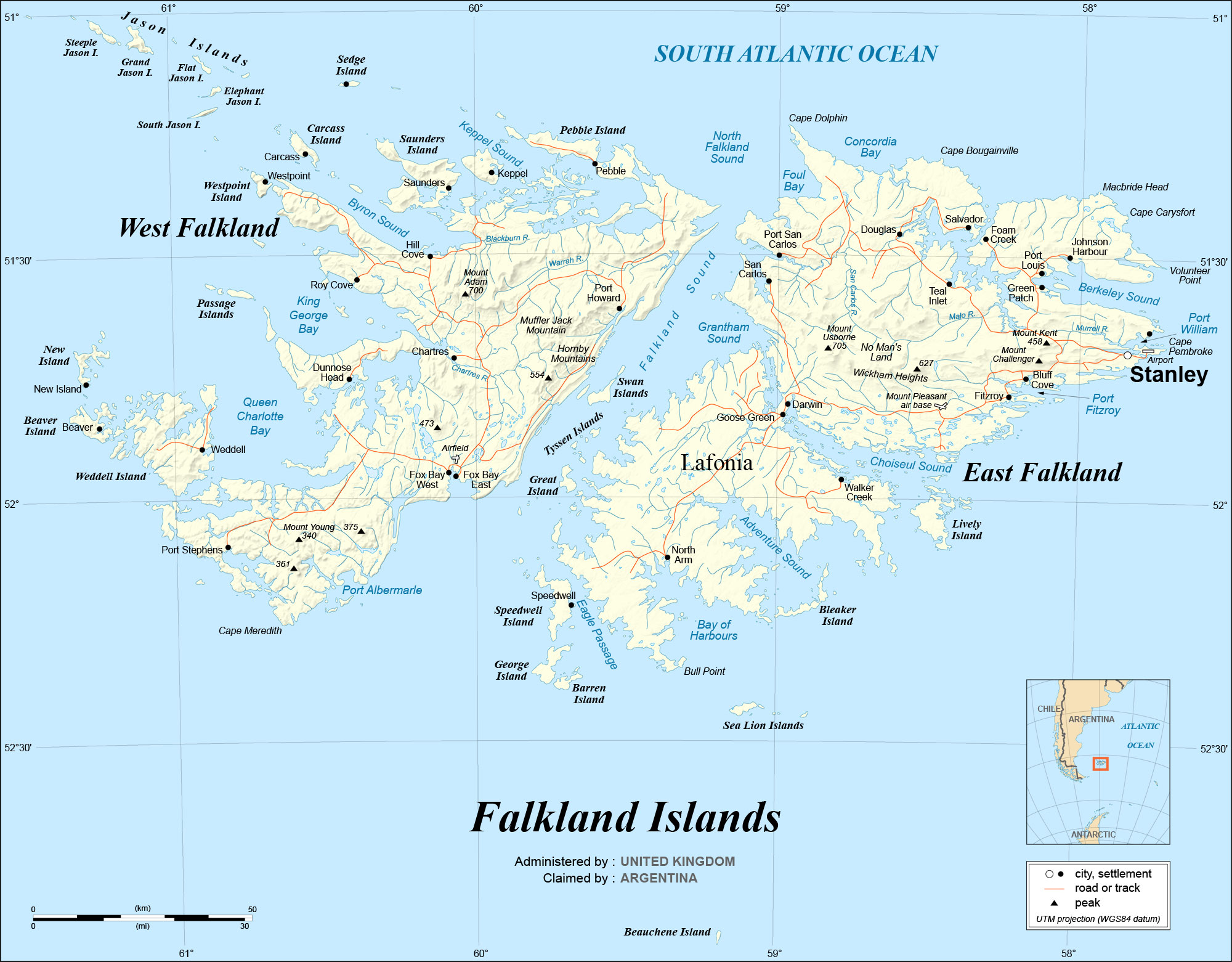

While it may sound like a mythical place, the Rendells’ ranch is no different from the neighboring farms scattered throughout the Falkland Islands, a tiny windswept archipelago about 850 miles north of the Antarctic Circle and 400 miles east of Argentina.

Home to around 3,000 people and roughly half-a-million sheep, the Falklands, a British territory, are a major wool producer. Besides being one of the only places in the world where sheep and penguins routinely share pasture, the Falkland Islands bear the distinction as the nation with the highest percentage of certified organic land. In the late 1990s, the local government pushed to get the entire group of islands certified organic as a way to boost the brand of Falkland Islands’ wool on the international market. Today, 36 percent of Falklands farmland is certified organic, and the extraordinarily fine, ultra-white Polwarth wool they export has a cult following among textile artists.

The Rendells purchased their farm, which occupies the entirety of Bleaker Island (one of the nearly 800 islets that comprise the Falklands archipelago) 16 years ago, though it has a been farmed continuously for more than 100 years. Mike Rendell says becoming certified organic was simply a matter of paperwork for he and his fellow Falklands ranchers because there was virtually no use of agricultural chemicals or livestock antibiotics on the islands. Serving organic steaks is one of the small luxuries afforded to tourists who come to stay in the Rendells’ solar- and wind-powered guest house.

“Although we weren’t certified organic until six or seven years ago, in fact we were always organic because we weren’t using anything other than natural products,” says Rendell, adding that “our livestock are all grass-fed.”

The sheep and cattle on Bleaker Island and elsewhere in the Falklands subsist largely on the native tussac grass, which grows in clumps up to 8 feet tall and forms extensive stands along low-lying coastal areas throughout the Falklands. In addition to providing year-round forage to the sheep and cattle, tussac swards serve as nesting grounds for local seals, along with 46 of the 65 bird species that call the islands home, including Magellanic penguins, which excavate subterranean burrows beneath the grass. The richness of the tussac ecosystem is the reason that wildlife and livestock are so commonly found cohabitating in the Falklands.

The habitat-sharing arrangement seems to work well for all parties involved. “You’ll see sheep walking right through the middle of the penguin colony, and the penguins don’t even turn a head,” says Rendell, laughing. “You don’t see a cow going up and licking a penguin or anything like that, they just get on with their own lives. They don’t seem to have any issues at all.”

In the past, however, there was an issue of too many sheep and not enough tussac. Bleaker Island was overstocked when they bought it, says Rendell, who has slashed the size of the herd by more than a third to ensure that the tussac can regrow enough each year to provide for both the livestock and wildlife.

In other areas of the world, the commingling of livestock and wildlife has led to devastating disease outbreaks as a result of pathogens jumping from one host species to another. But Rendell says this has never been an issue in the Falklands in part because ruminants aren’t closely related to seabirds, penguins, or sea lions, but also because livestock in the islands rarely suffer from disease. “The livestock here is in very good condition in terms of disease because we are so insulated from the rest of the world,” says Rendell.

The islands’ geographic isolation helps prevent the introduction of exotic pathogens, but the Falkland’s government maintains strict protocols to avoid contagion from abroad. When the Rendells brought in Hereford steers from Chile to start their cattle herd 10 years ago, the animals went through “a very serious quarantine regime over about four or five months. Lots of testing and all sorts of things had to happen,” Rendell says.

Sheep on pasture by a traditional Falkland Island home. Copyright Jean Crankshaw 2016

Ample grasslands, low-stocking densities, and nearly nonexistent disease pressure has made organic methods the default approach of Falkland’s ranchers. In the Falklands, there is no need for sheep dipping, where the animals are literally bathed in potent parasiticides, nor mulesing, the controversial practice of removing the skin from the backsides of lambs to avoid the fly (and maggot) infestations that can build up in dung-encrusted fur when sheep live in unsanitary conditions – neither of which are permitted under organic standards.

While the Falklands may sound like a pastoral paradise, there are drawbacks to living and farming in such a remote place. Supplies come only every six weeks to Bleaker Island, via an expensive eight-hour boat ride from Stanley, the capital. The same boat delivers new breeding stock to improve the genetics of the herd, and carts off animals to the Falkland’s only abbatoir. Corralling livestock onto a beached boat isn’t easy, says Rendell.

Yet getting humans back and forth to East Falkland Island where Stanley is located – what folks like the Rendells who live on the many remote islets refer to as “the mainland” – is surprisingly easy. The government runs an air taxi, which Phyllis Rendell, who is an elected official in Stanley, uses to get to work each week. It’s just a half-hour plane ride, and the fare is heavily subsidized for residents. “You just phone in a couple days beforehand and say where you want to go,” says Rendell. Roundtrip airfare for tourists runs about £150 (about $219), which is nothing compared to the steep cost of flying to Stanley from Europe or North America. Bleaker has beds for only twelve guests at a time, which are generally filled with camera-toting naturalists – the cross-species interactions are a photographer’s dream.