An excerpt from the new book "Gilded Age Murder & Mayhem in the Berkshires."

John Ten Eyck, a black farm laborer, was soon accused of the killings. But was he the real murderer or just an easy scapegoat the authorities pinned the crimes on?

On the evening of Nov. 29, 1877, just after 5 p.m., as a light snow began falling, Ten Eyck stopped 15-year-old John Carey Jr., on the road that led to the farm. Carey worked for David Stillman and his wife, Sarah, doing farm chores, including milking the cows. Ten Eyck inquired whether the Stillmans sold butter and if they had any guests that night. The boy told him that they did indeed sell butter, but was unaware if they had any company that evening. Ten Eyck thanked him for the information and headed south towards the Stillmans’ farm.

Carey, the last to see the elderly couple alive – besides the killer – was also the person who discovered the murders the next morning. The scene he found was bloody beyond comprehension. One newspaper described the crime as “one of the most brutal human butcheries ever committed in New England.” While this may have been mere hyperbole, the scene was indeed gruesome.

That morning, Carey went to the farm and began doing his chores in the barn without going inside the home. He fetched the milking pail and milked the cows as usual. Carey hauled the milk to the house. Inside, David Stillman sat on the couch in which Carey had last seen him, but something was wrong. The man was dressed as he had been the previous day, but his outfit was now drenched in blood from a massive head wound. There was blood smears leading to the cellar and a bloody handprint on the wall. Sarah Stillman was found in the cellar and had also been killed by axe blows to the head.

Was he the real murderer or just an easy scapegoat the authorities pinned the crimes on?

It didn’t take long for the investigation to focus on Ten Eyck. Circumstantial evidence began to mount, helped along by Ten Eyck’s reputation as a drinker and petty thief. But Ten Eyck didn’t have a history of violence and his criminal record was miniscule. The authorities didn’t bother with any other suspects even though there were any number of tramps who traveled through the area and could have been responsible for the killings. Just a year before, an itinerant worker had attacked an elderly couple at their rural farm in nearby Otis, Massachusetts, beating the husband, and killing the wife with an axe.

When Ten Eyck was arrested he was shocked to learn he was accused of killing the Stillmans. An angry mob of more than 200 people with lynching on their minds waited for the prisoner to arrive at the jail. The police and sheriff’s deputies kept the crowd at bay and Ten Eyck was safely brought inside and locked up.

Sitting in jail in Pittsfield Ten Eyck began to write down his life story. Born in Lenox around 1832, he was the son of a local woman, Orrilla Mariah Fletcher, and William Henry Ten Eyck, a former slave from New York who had escaped to Massachusetts. He grew up in foster care and the old couple who looked after him and his brother were barely given enough to properly take care of the children. Ten Eyck wrote that “Old Berkshire, my birthplace, makes the most limited provision” for the poor than any other place he lived. He said no other county could “match injustice and oppression of the poor.” When he turned 15, his school days were done and he became a full-time farm hand.

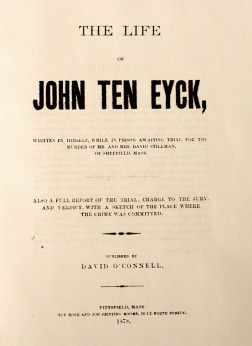

The title page for John Ten Eyck’s autobiography written while he was awaiting trial for a double murder.

The trial in Pittsfield, the county seat, began on May 15, 1878 and lasted four days. The lead defense attorney, Herbert Joyner, told the jury that this was a “double tragedy” in that the police and public, based on skimpy circumstantial evidence, immediately blamed Ten Eyck for the crime instead of following up on other leads and potential suspects.

The lead defense attorney told the jury that this was a ‘double tragedy’ in that the police and public immediately blamed Ten Eyck for the crime instead of following up on other leads and potential suspects.

The all white jury spent only a few minutes deciding Ten Eyck’s guilt. As soon as they were in the jury room they took a straw poll and found they all agreed he was guilty of the murders. To keep up appearances, they waited for a little over an hour before coming back with the verdicts. Before being sentenced, Ten Eyck stood before the judge and told him he was innocent.

“They are the facts and as I also told the jury nothing but the truth in any form, that is all I have to say, sir.”

At 10:45 a.m., August 16, 1878, he was escorted to the scaffold and as 250 people looked on, Ten Eyck firmly and deliberately made his way up the stairs and stood on the trap door. The Rev. Samuel Harrison, a black minister who had served with the famed Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War, gave the man a final prayer. Ten Eyck refused to give a speech. A black cap was placed over his head, followed by the noose. The executioner pulled the lever and Ten Eyck dropped. He died almost instantly.

His body was sent to his family in Blandford, Massachusetts, for burial, but in a final indignity to a man whose whole life had been filled with them, his father-in-law exhibited Ten Eyck’s body at 10 cents a head outside a train station and made $350, before finally putting Ten Eyck’s remains to rest.

This story, in a different version and under the title “The Thanksgiving Day Double Murder,” is taken from Andrew Amelinckx’s recently published book, “Gilded Age Murder & Mayhem in the Berkshires,” by The History Press.