A vegan writer on a meat eater's book.

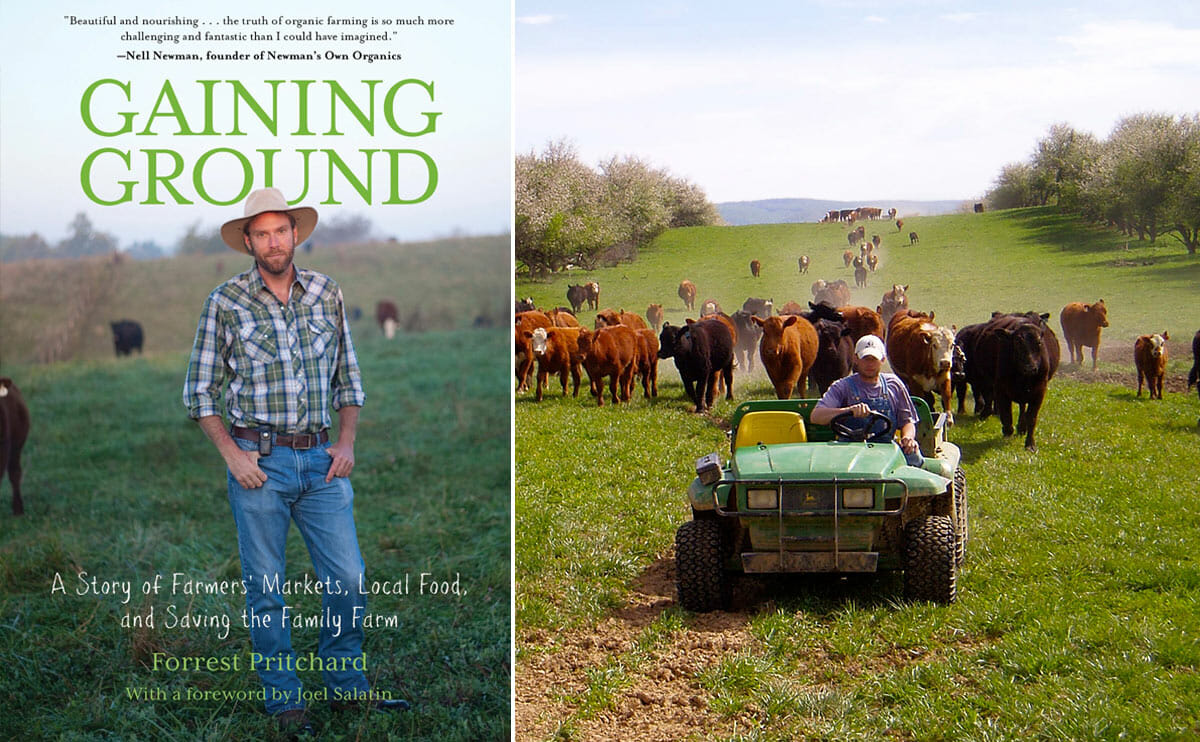

We were on a panel together at a food festival in Maryland – sitting on a dais, swatting bugs and talking about local food – and he began by apologizing for being out of it: he’d been up since dawn packing his pickup for the Arlington, Virginia, farmers’ market. But Pritchard wasn’t out of it. He was funny and sharp and altogether with it. Afterwards, he handed me a copy of his book – Gaining Ground: A Story of Farmers’ Markets, Local Food, and Saving the Family Farm – inscribing it with the phrase, “Here’s to a sustainable future.”

We’ll see about that, I thought. You see, I’m a historian and writer who has focused my career on animal ethics and, after a decade of thinking systematically about animal domestication, I’ve reached the conclusion that bringing farm animals into the world, much less killing them, is (in most circumstances) a moral atrocity. And Pritchard makes money exclusively off animal products.

I started his book (skeptically, mind you) on the ferry ride back to my hotel. By the next morning I was done. I couldn’t put the thing down. Something rare had happened: I was charmed.

Gaining Ground is the story of Pritchard’s quest to salvage and revive his family’s farm. It’s a common American drama – saving the old farmstead – but this is an uncommon narrative. Pritchard, in welcome contrast to his evangelical-libertarian mentor (and fellow Virginian) Joel Salatin, relates his experience with humility and wit, eschewing brimstone revivalism for guileless storytelling. In prose graceful and measured, he evokes an agro-literary tradition akin to Louis Bromfield’s Malabar Farm and Masanobu Fukuoka’s The One-Straw Revolution. The fact that Pritchard manages character development and plot twist with the finesse of a seasoned novelist (he was a literature major at William & Mary) hardly hurts.

But Pritchard’s vocation is to raise and kill sentient animals. So when I closed his book I found myself in a paradoxical spot: completely taken with the narrative but repulsed by the activity that made it possible.

It’s a common American drama – saving the old farmstead – but this is an uncommon narrative.

What lured me in? What kept me rapt? What triggered my empathy and tempered my scorn? The first thing I realized (and appreciated) is that Pritchard writes about farm life with unvarnished honesty. If there’s one quality that has sapped verisimilitude from the agrarian literary tradition – from Jefferson to the present – it’s the tendency to whitewash the general shittiness of farm work. The agricultural canon is larded with so much pastoral pap that we’ve failed to ask why, if farming is such a deeply fulfilling career, farmers throughout history have dropped the hoe and ditched the endeavor the moment they could.

Pritchard never succumbs to such seduction. But he never drops the hoe either. On Smith Meadows Farm, life is grueling but tolerably so. Everything breaks, nothing behaves as it should, and the workday is incessantly rocked by rogue variables, many of which bite, destroy property, get drunk, have panic attacks and run away. Capturing the essence of farm work, Pritchard explains to his young nephew, “If anyone ever asks what we do on the farm, don’t tell them we raise cattle, or chickens, or sell meat. Just say this ‘we fix things.’” Things break. Pritchard abides.

Not only is Pritchard’s humility and Job-like patience a breath of fresh air, but his unadorned writing style imbues his loftier pastoral reflections with sincerity. Slowly, like mist lifting off the pasture, Pritchard’s account reveals how the relentless nature of work on a beautiful small farm can alter a farmer’s inner sense of self. When – in a brief paean to “slow food” – he writes, “As I entered my late twenties, I found myself moving at a more tranquil pace as well, finding a rhythm with the subtle changes of the seasons,” nothing about the description comes off as waxing indulgent or overblown.

Pritchard writes about such topics as soil with obsessive affection, without ever being overly poetic or earnest. The simplicity of soil health, he explains, “floored me.” The implications of soil farming “exploded like fireworks in my young mind.”

But what about the animals that make soil health possible? Pritchard isn’t nearly as attentive to their sentience as he is to the epiphany-inducing potential of the soil they enrich. His farm is dedicated exclusively to the commercial production of animal goods. At the farmers’ market (where he does all his sales) he offers beef, pork, chicken and eggs (the vegetables he does grow, he explained in an email, are bartered with neighbors). There’s absolutely no doubt that Pritchard, who interacts with his animals daily, understands that these creatures are, as the philosopher Tom Regan puts it, “the subjects of a life.” That is, they experience pleasure and pain and have a clear sense of identity. Point being: they don’t want to end up at the farmers’ market.

Evidence of Pritchard’s awareness of animal sentience abounds in Gaining Ground and it makes for some of the book’s more powerful moments. Goats, he observes, “have distinctive and charming personalities.” When one of them, Pedro, gets into some mouse poison and dies, Pritchard writes, “I felt like I had betrayed a friend.” He recounts a farmhand’s touching childhood story of a pig who walked him to the school bus stop every morning and waited there until he returned later in the day. Pritchard himself recalls a less pleasant but equally compelling experience with another pig that, as others were being corralled for slaughter, sensed its fate and bolted. Pritchard gave chase for hours. The pig eventually turned on him with a vengeance, chasing him up a tree and holding his petrified human farmer at bay. A near-broken ankle (from jumping down) and a hired Amish sharpshooter were involved before the ordeal came to an abrupt end. How can one simply think of animals as objects after such an experience?

The first thing I realized and appreciated is that Pritchard writes about farm life with unvarnished honesty.

Red flags unfurl when Pritchard speculates that his pigs “were ready for their trip to the butcher.” Really? Such a remark suggests that Pritchard falls prey to what I’ve elsewhere called the “omnivore’s contradiction,” a self-interested non-position position that allows for the simultaneous recognition of animal as subject and object. While they live, Pritchard’s animals are subjects worthy of moral consideration; but when they reach a certain weight, moral consideration disappears and the animals become objects to kill, sell and eat. At one point near the book’s end, Pritchard writes of his farm, “Instead of taking, we were leaving.” But I’m not convinced the animals would see it that way. Nothing, at any rate, is done to address, much less resolve, this contradiction.

And still. For all of the unnecessary violence and for all Pritchard’s failure to think in consistent ethical terms about animals, it nonetheless occurred to me that, in conveying his journey, he is – in a weird way – extending a friendly hand to animal rights advocates. He’s saying – no, he’s showing – that his paradigm, although it kills sentient animals, is better than the dominant paradigm, which kills more animals under worse conditions. He’s saying that his passion for honest agriculture and his ability to sustain a meaningful vocation is a critical step in the direction of a future agricultural model that leaves room for a fuller conception of justice. Animals might not be treated with ethical consistency on Pritchard’s farm, but the minimal suffering they endure can be seen as a down payment on a future in which they don’t suffer at all.

Forrest might not see it that way – the man has bills to pay. But his moving account of agricultural life has allowed me to keep dreaming.