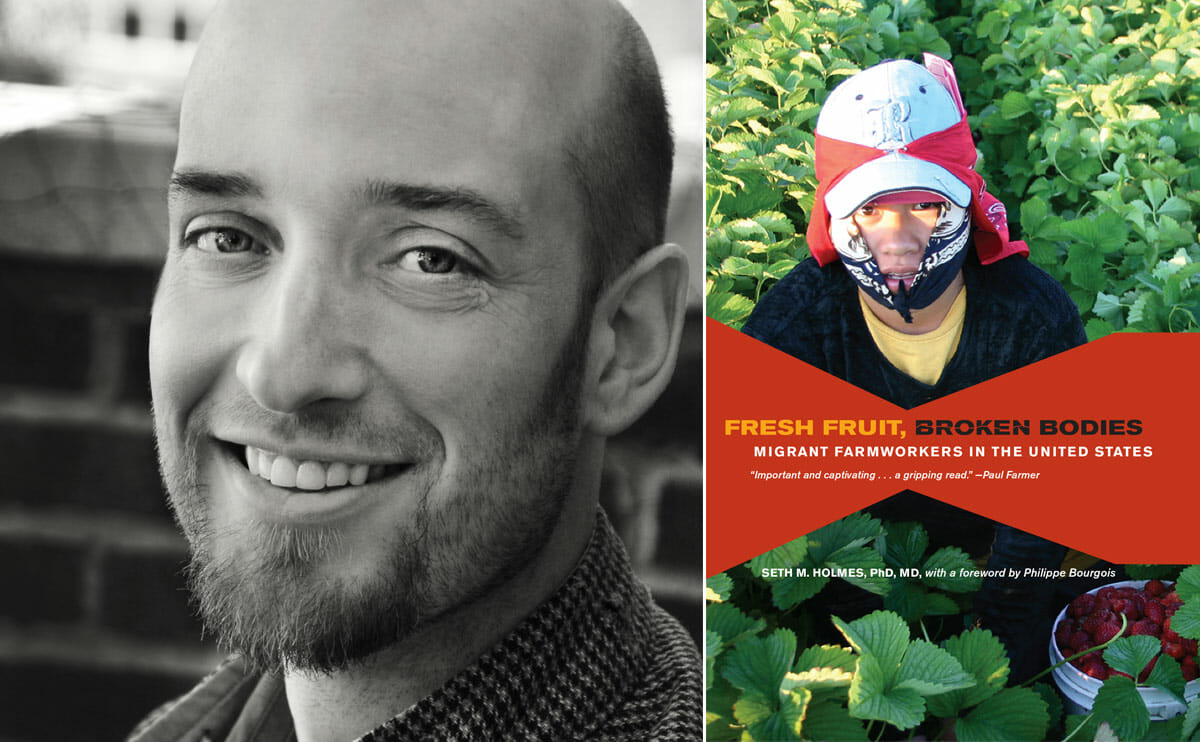

Today's pickers - migrant farm workers picking produce across the country - are Mexican immigrants, many of them indigenous peoples. Author Seth M. Holmes spent years with these peoples while working on his book.

“The pickers come from the most vulnerable populations at any given time,” writes Seth M. Holmes in Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States.

Today’s pickers – migrant farm workers picking produce across the country – are Mexican immigrants, many of them indigenous peoples. Holmes spent years with these peoples while working on his book.

Holmes, an anthropologist and medical doctor, worked in the fields, stayed in labor camps, and made the treacherous trip from Mexico to the West Coast with a group of migrant workers.

In his book, Holmes balances pulling the reader into specific details of his life and the lives of the migrant workers, with larger discussions on how migrants are impacted by social hierarchy, the medical professions inability to adequately help the very poor, and our role in these overwhelming issues.

“It is likely that the last hands to hold the blueberries, strawberries, peaches, asparagus, or lettuce before you pick them up in your local grocery store belong to Latin American migrant laborers,” Holmes writes. Ultimately his book leaves readers asking, “How might we respect this intimate passing between hands?”

We asked Holmes about his experiences and the current issues facing migrant farm workers.

Modern Farmer: Why was it important for you to experience and not just document the plight of the migrant farm workers?

SH: For me in particular doing participatory observation, which a couple anthropologists have called “deep hanging out,” I learned a lot of things that I wouldn’t have learned if I had done observations and interviews.

Some of those things are as simple and important as living in the labor camp as opposed to coming every day and doing interviews but living in an apartment somewhere. It helped me understand how hard it is to sleep in the labor camp. The fact that everyone wakes up at four in the morning to get their kids ready to go to day care and to school before they go to the farm to pick. The fact that in the fall during blueberry season the humidity from your breath freezes on the underside of the tin roof at night when it’s below freezing and then when the sun rises in the morning all of that humidity rains down on you and all your things and if you haven’t already woken up to go pick you get woken up by that. The lack of insulation and the fact that a lot of people leave their gas stoves on in their camp cabins for heat, which gives off a lot of fumes that shouldn’t be breathed all night long by families. So a lot of those things I wouldn’t have even thought to ask about.

I would have known from observations and interviews that picking strawberries is difficult work and that people have some pesticide exposure and bad backs and knees. But I wouldn’t have known personally how somewhat impossible it was to actually do. I picked one or two days a week. They pick seven days a week. The rest of the days I interviewed people, I observed in the clinic, I observed some of the supervisors

But the days that I picked, no matter how hard I tried to pick, no matter how much I tried in my mind to put myself in a mindset where my life and my survival really depended on picking fast and picking effectively, I never was able to keep up with the pickers next to me, and I never was able to pick the minimum weight. I got close a couple of times and was proud of myself, but I never was able to pick the minimum weight. Which then also really made me question the idea that these pickers are unskilled workers. Because they are very skilled.

MF: You documented a specific group of indigenous Mexican farm workers, the Triqui people. Are their stories a stand in for all migrant farm workers? How are they different, and how are they the same?

SH: I think that a lot of their living conditions, working conditions, crossing the boarder conditions and so on are very similar to all migrant farm workers in the U.S. today, from Mexico, from Central America, from all different ethnic groups in Mexico.

The way that indigenous Mexicans and I think indigenous Central Americans too, are different [than other migrant farm workers] is that they have what we in anthropology might call “more structural vulnerability,” in the sense that they are made more vulnerable by social structures. In Mexico and the U.S. there’s an ethnic hierarchy where the indigenous people are treated either as less important or less knowledgeable or less skilled than the other Mexicans and that effects them at home in Mexico and here at farms.

MF: In addition to being an anthropologist, you’re also a medical doctor, can you discuss how this played a role in your research and how immigrants’ medical conditions are an important part of the story of migrant farm workers?

SH: The title of the book is partially about the transaction of these people coming from Mexico working so hard to give us healthy food in our grocery stores and in our farmers marketÂ. They are working so hard to do that that they are becoming unhealthy. It’s an almost direct transaction of our health in exchange for their bodies becoming injured and sick and broken.

On one hand I write about the health conditions simply because the working conditions and living conditions of these people inherently produce bad backs, bad hips, knee injuries, pesticide exposure, sometimes dehydration and sun stroke, preterm births. A lot of these things are super common with migrant farm workers.

Part of what really interested me in the book was how these living and working conditions that produce these health inequalities, how are all of these hierarchies and inequalities understood to be normal and natural? How did they become taken for granted to such a degree that the American public tends not to care about it that much?

MF: What can the immigration bill, which has currently only been passed by Congress, do for migrant farmers?

SH: I think that having a legal way for people to come to the U.S. and work and a legal way for them to be on a path toward full legalization, citizenship or green cards is super important. It decreases fear and it decreases that power hierarchy between employers and workers. A lot of the labor laws are not enforced on behalf of migrant farmers because there’s so much of a power hierarchy.

While immigration reform is very important, one thing that is problematic is all the focus on border protection, which is, at this point, according to all the evidence we know, leading to more people dying at the border. Because the border has this policy of prevention through deterrence which explicitly encourages migrants to cross at the most dangerous parts of the desert.

And the farm workers I know, they were telling me that the main thing they want is they don’t want to have to cross the border illegally because its too dangerous. They want worker protections to be valid and enforced.

The Triqui people specifically have been migrating to the U.S. more and more since NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) was signed, and the way that I understand it is that NAFTA made it illegal for signatory countries to pass tariffs on other country’s farm goods, but didn’t make it illegal for other countries to have subsidies. The U.S. has increased subsidies by over 300 percent since NAFTA, which is essentially the exact same thing as a tariff but in reverse and only a wealthy country can do it.

The reality is that on some level they don’t want to come to the U.S. to work in the first place. They are subsistence farmers from Oaxaca; they are indigenous people who want to be living in their ancestral land doing the farming that their ancestors have been doing for 500 years or more.

MF: Why do you think there is a disconnect between our concern for the health of our food and the health of the people farming our food?

SH: It appears to me that a lot of us who have enough money to prioritize organic and buy food that we think is good for us, we are overall kind-of selfish. We care about how our food is going to affect us and our bodies, but it’s harder for us to care about how it affects the bodies of the people who picked it for us.