In October 1955, U.S. Intelligence Report No. 6884 warned that the United States was facing a new Cold War threat. But the threat wasn't bombs or spies, or anything from the usual James Bond plot - it was agricultural exchanges.

In October 1955, U.S. Intelligence Report No. 6884 warned that the United States was facing a new Cold War threat. But the threat wasn’t bombs or spies, or anything from the usual James Bond plot – it was agricultural exchanges.

The previous summer, the U.S. and the Soviet Union made headlines around the world by sending official delegations to each other’s farms. Twelve Americans toured Soviet collective farms from Moscow to Kazakhstan; the twelve Soviets visited fields and research stations from Iowa’s golden grain fields to California’s sunny citrus orchards. Even though the Soviets uncovered no “new” information on American farms, the warning was dire: according to the report, classified until the mid-2000s, the Soviets had racked up a “considerable advantage,” and any future exchanges should be planned “like a military campaign.”

What exactly had whipped officials into a such a frenzy? And how did this farm exchange even happen?

The agricultural trips came at a moment in the Cold War where joint visits were very rare. Both nations had recently exploded hydrogen bombs, but Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953 also opened the door for friendlier relations. As part of new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s policy of “coexistence,” the Soviet Union had cautiously begun admitting American visitors. Between 1953 and February 1955, 101 Americans entered the Soviet Union as private citizens. But in the U.S.,a 1952 law – passed at the height of the Red Scare – barred Communists from entering the country unless they were conducting “official business.” An entire series of cultural exchanges between youth groups, orchestras, newspaper editors, and wrestling teams got caught up in red tape, with the admission of Soviet citizens requiring fingerprinting and individual exemptions from the U. S. Attorney General’s office. The ironic result was a PR coup for the Soviet Union, which suddenly seemed like the more open and, well, freer, country.

[mf_video type=”youtube” id=”7mVibCaSk1s”]

A Universal Newsreel covering the 1955 visit. (Coverage begins at 2:46)

This was the context in which Lauren Soth, the editor of the Des Moines Register, published a daring February 10, 1955 editorial inviting Khrushchev to visit Iowa’s famous farms. (The editorial won him the 1956 Pulitzer Prize, and you can read it here.) Soth wrote that he was acting without “diplomatic authority of any kind,” and invited Khrushchev to come to Iowa to “get the lowdown on raising high quality cattle, hogs, sheep, and chickens.” He promised not to withhold any “secrets,” stating plainly that the United States should “let the Russians see how we do it.” And then he boldly called out U.S. and Russian officials for their cowardice: “Of course the Russians wouldn’t do it. And we doubt that even our own government would dare to permit an adventure in human understanding of this sort. But it would make sense.”

But, to everyone’s surprise, Khrushchev accepted.

The Russian leader had a history of interest in agricultural innovation, having previously acknowledged the failures of the Soviet collective farms. In a speech to the Central Committee of the Communist Party earlier that winter, he urged the planting of hybrid corn – a dramatic reversal of previous Soviet agricultural policies that had downplayed, or even denied, the scientific basis of Western genetics.

From the report:

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]The exchange afforded the USSR the opportunity to acquire first-hand knowledge of American agricultural production know-how and to obtain expert critiques on Soviet agricultural shortcomings. The attitude was marked by a willingness to advise and assist the USSR in overcoming production difficulties, without any expectation of gaining similar benefits from Soviet agriculture. The US delegation was at a serious disadvanage in gaining information on Soviet agriculture partly because Soviet control was strict and partly because the delegation members on the whole were unfamiliar with Soviet agricultural conditions. Both sides were afforded the chance to make a popular impact, but again the Soviet delegation was at an advantage.[/mf_blockquote]

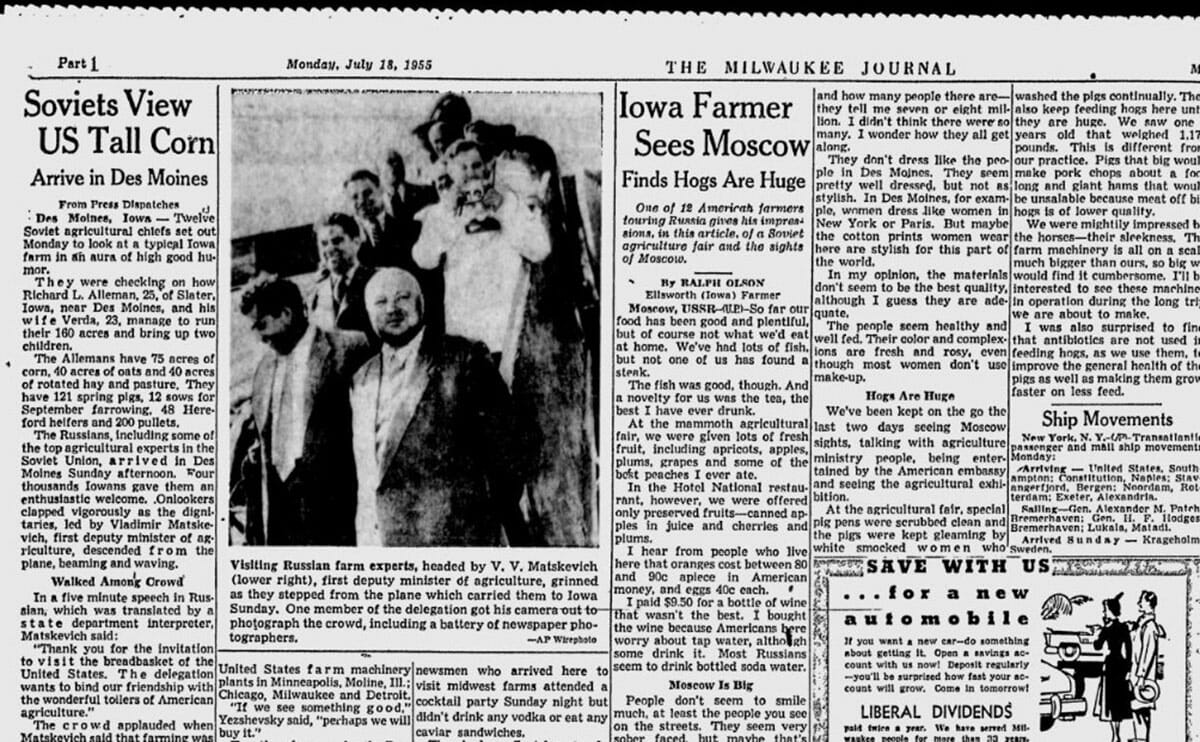

Although Khrushchev himself wouldn’t come for four more years, by March, the Soviet Foreign Office had placed an official request to send an agricultural delegation to the United States. A minor diplomatic kerfuffle as the State Department scurried to find ways to admit the Soviets. The Soviets solved the problem for them by calling the delegation’s members “official” government representatives instead of private citizens, a diplomatic sleight of hand that skirted restrictions on Communists’ entry into the country. The Soviet group, led by the First Deputy Minister of Agriculture, included several high-ranking officials and specialists; the Americans sent successful farmers, professors of agriculture, and Soth.

Following Soth’s original invitation, the Americans freely shared their expertise, and the Soviets witnessed, first-hand, the high-tech tools that were filling American silos with surplus grains. The Soviets, the intelligence report noted, “relentlessly” pursued information on practical details that could kick-start Soviet agriculture, especially anything related to livestock production. And this, according to critics at the State Department and the CIA, was the problem. The Soviets designed their visit to the U.S. as a “concentrated course in American farm technology.” American experts freely gave the Soviets advice on everything from the most efficient use of pesticides to the benefits of contour plowing. Meanwhile, the Americans returned home without so much as recent statistics on cotton production – unlike the chatty Americans who traveled to the Ukraine, the members of the Soviet delegation to the U.S. were “highly adept at withholding facts” from their hosts. The report even griped that “the Soviet press gave considerably less attention to the visit than did the American press.”

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]Soviet news coverage of the trips stressed the atmosphere of good will; the peace aspirations of both peoples; the desirability of further exchanges; the freedom of the US delegation to travel at will; American praise of Soviet agriculture; and the “exhaustive” answers” (which were not printed) of Soviet representatives to American questions. Suppressed or soft-pedaled were suggestions of US superiority; US criticism of excessive banqueting; Soviet insistence that Americans adhere rigidly to the original itinerary; direct reference to Soviet biologist Lysenko; unanswered US requests for information.[/mf_blockquote]

The intelligence agencies’ qualms were based on the belief that the U.S. and the Soviet Union were engaged in a head-to-head battle of military and economic might. But in years immediately following the first farm exchange, the Cold War increasingly became a contest of hearts and minds. And that meant that friendly Iowans and their hybrid corn had suddenly become more useful weapons in promoting the supposed superiority of the American way of life than any bomb.

Eventually, more liberal foreign policy voices in the State Department won out, and the floodgates opened: scientists, housing experts, coal miners, dance troupes, and symphony orchestras soon followed Soth’s footsteps. By the time Khrushchev finally stepped foot in an Iowa cornfield in 1959, cultural exchange had become a central weapon in the ideological Cold War.

Audra J. Wolfe is a writer and editor based in Philadelphia. She is the author of Competing with the Soviets: Science, Technology, and the State in Cold War America.